When political cartoonist Mahmoud Abbas published a cartoon on the decline in international oil prices during the coronavirus pandemic earlier this year, he received a barrage of death threats and online harassment.

One day after he posted the cartoon, Abbas woke to find his Twitter feed overwhelmed. The cartoon had been retweeted over a million times, attracting commenters who threatened his life, posted personal information about his family, and accused him of mocking Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

"I was shocked," Abbas, a freelance Palestinian cartoonist based in Sweden, told VOA. "I [didn't] understand the reason."

Abbas is one of at least 12 journalists to be threatened or harassed for their work in recent months, according to the Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI).

From late March to early May, the CRNI documented more than double the number of cases than the previous two months.

On June 15, CRNI, along with the Cartoon Movement and Cartooning for Peace, released a joint statement condemning the attacks and death threats.

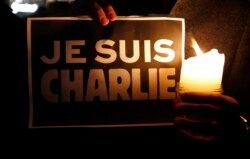

"It is a scant five years since the attacks at Charlie Hebdo; death threats against cartoonists are still regarded with the utmost seriousness by police forces across Europe and lead to great levels of distress for those so threatened as well as their families," the statement said.

Gunmen attacked the Paris-based satirical magazine in January 2015, killing several journalists, staff and security.

Tjeerd Royaards, the editor-in-chief of Cartoon Movement, said that the pandemic is not the instigator of the problems, but it is worsening them.

"We've seen in recent years that press freedom is declining," Royaards, who is in Amsterdam, told VOA. "The lockdown kind of presented a great opportunity for all these authoritarian regimes to use lockdown measures to [further restrict] press freedom."

One of the cases CRNI documented was that of Rafat Alkhateeb, who faced online harassment in late May over a cartoon on Facebook depicting Jordanian Prime Minister Omar Razzaz. The cartoon showed Razzaz in a position similar to the one used by a police officer arresting George Floyd, an African American who died in police custody in Minneapolis on May 25.

Alkhateeb, who works in Jordan for the Lebanese news outlet Al Mayadeen TV, said social media users accused him of being a foreign infiltrator and called for his prosecution.

Alkhateeb said he took the cartoon down over fears that he could be prosecuted over the false claims of foreign infiltration. The country's security and broad terrorism laws are sometimes used to prosecute journalists, Reporters Without Borders has found.

"It was one of the most terrible nights because when you read the comments on social media, you say, 'OK, if the government saw this comment, now they would have a reason for suing me for this cartoon,'" Alkhateeb told VOA.

Other incidents were related to governments' handling of the pandemic.

Authorities on May 6 arrested Bangladeshi cartoonist Ahmed Kabir Kishore over a series of cartoons about politicians titled "Life in the Time of Corona." He faces a possible life sentence for "spreading rumors and misinformation" and "insulting the image of the father of the nation, the national anthem or national flag."

International bodies have raised concerns about the recent rise in threats against cartoonists. Earlier this month, the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, the European Federation of Journalists and other rights groups called for more protections to be in place for cartoonists across Europe.

Royaards said joint statements are important because most cartoonists are independent and lack protections that other journalists receive from organizations.

"That's why it's extremely important that there are cartoonist organizations out there that put them on the map, that try to raise awareness for this group," he said. "And then try to point out the fact that cartoonists are also getting in trouble because of press freedom restrictions and that that situation is getting worse."

When press freedom becomes a threat in certain countries, Royaards said cartoonists are especially vulnerable because of the visual nature of their work.

"Visuals are so powerful," Royaards said. "So the power of cartoons, if they are published in newspapers, on a website, is you cannot skip a cartoon. Once you've seen it, you've seen it."

Abbas, the Palestinian cartoonist, shared a similar view. Unlike other types of media, cartoons can be easily accessible worldwide.

"Pictures can describe itself without letters, without words," he said. "The cartoon has no language. You don't need to speak a lot of languages to understand the cartoon."

Royaards said the threats against cartoonists are dangerous.

"Cartoonists are one of the most visible parts within free media and also one of the most critical parts because the bread and butter of what they do is to make fun of those in power, to criticize those in power," he said. "I think that's the reason why they're often one of the first ones to be targeted."