To arrest an exiled critic, Belarus did something that no other government had previously done: it used a fabricated bomb threat and a military jet to force a civilian plane in its airspace to land in the capital, Minsk.

On board the flight from Greece to Lithuania was 26-year-old Raman Pratasevich, an activist and blogger. When the plane landed, he was taken into custody.

Pratasevich was the editor-in-chief of the popular Telegram channel Nexta, which serves as a powerful medium for Belarus’s opposition voices. Pratasevich was wanted in Belarus, where he was on a list of terror suspects and accused of inciting unrest during last year’s protests over the disputed presidential election.

Since his arrest, Pratasevich has appeared on state television to give statements widely seen as being made under duress. His family and rights groups pointed to marks and bruising visible in the videos, which they say show he is being beaten and abused.

The incident has caused a global outcry, with Western governments threatening to sanction key sectors of the Belarus economy and the European Union banning Belarusian planes from Europe’s airspace.

While extreme, the Belarus case is not an isolated incident. Authoritarian governments continue finding ways to abduct or even kill critics, journalists, activists and opposition figures living in exile.

The most egregious was the 2018 killing of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in a Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Earlier this year, the administration of President Joe Biden declassified an intelligence report that concluded that Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman approved the operation in Turkey "to capture or kill [the] Saudi journalist.”

Nate Schenkkan, director of research strategy and co-author of the Freedom House report “Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach,” says governments going after critics beyond their jurisdictions are in clear violation of international law.

“Killing someone extraterritorially without any judicial processes is completely illegal obviously. Kidnapping someone is completely illegal, disappearing someone is illegal and additionally diverting and grounding … a commercial airliner using a fighter jet, there's no question about that, this is a totally illegal operation,” he told VOA.

Cross-border ‘abduction’

Ankara was outspoken about Khashoggi’s killing in Istanbul, and in November last year held a trial in absentia for nearly two dozen Saudi operatives whom it alleged were involved.

But Turkey joins Belarus, Vietnam, Tajikistan, and Iran in having managed to pull back individuals who had fled into exile.

In some cases, journalists, bloggers and activists are abducted from the streets and forcibly returned.

Truong Duy Nha, who wrote blogs for Radio Free Asia’s Vietnamese-language service, a sister-organization of Voice of America, had fled Vietnam in December 2018 for Thailand, where he was seeking asylum with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees.

Weeks later, he was abducted near a mall in the capital Bangkok and transferred back to Vietnam, according to his Canada-based daughter Doan Truong.

In March 2020, Truong Duy Nha stood trial in Hanoi and was sentenced to 10 years in prison for defrauding the public while working for a state-run news outlet.

The journalist’s daughter told VOA he is forced to do labor and because of COVID-19 restrictions, the authorities have not let family members and friends visit him for months.

“My dad is required to work from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. with an hour lunch break, five days a week. His work involves crafting and weaving baskets,” Truong said.

Others in exile are lured from their country of exile with incentives, like Sharofiddin Gadoev, a political activist from Tajikistan, who had political asylum in the Netherlands.

Gadoev said that in 2019, he was invited to Moscow to meet a high-level official.

It was a trap. "Instead of the meeting I was kidnapped, beaten and forcibly sent to Tajikistan,” he said.

“When I was detained in the territory of the Russian Federation, there was not a procedure and extradition,” he told VOA by email. “It was an abduction.”

He credits his freedom to efforts from governments in Europe and the United States, as well as international rights groups.

In some cases, authorities claim threats to national security to secure extraditions.

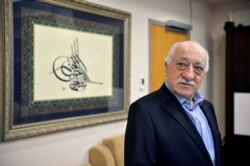

In March 2018, Turkish intelligence captured six Turkish nationals living in Kosovo. They were brought back to their home country to face terrorism charges over their alleged affiliation to a grassroots movement led by U.S.-based Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen, listed as a terrorist by Turkey. Gulen is accused of masterminding the 2016 failed attempted coup—a charge he denies.

“Wherever they may go, we will wrap them up and bring them here,” said Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan about the operation.

Schenkkan, of Freedom House, said Kosovo cooperated with Turkey by revoking residence permits “on national security grounds.”

“There's kind of a fictional legal process. I say fictional because these people were given no opportunities to see the basis on which their residency was being revoked. They were given no access to counsel or to lawyers to help contest it,” he added.

Kosovo’s prime minister later dismissed the country’s interior minister and secret service head for not briefing him about the arrests, Reuters reported in 2018.

More recently, Turkish state media published photos showing Gulen’s nephew, Selahaddin Gulen, in handcuffs after he was forcibly repatriated from an unnamed foreign country.

Those forced to return often face imprisonment or even death.

Dissident journalist Ruhollah Zam had political asylum in France, where he ran Amad News, a popular Telegram news channel. Iran said the website had incited widespread protests in 2017 and 2018.

In 2019, Zam was lured to Iraq with the promise of a high-profile interview. But Iranian agents abducted him, and authorities brought multiple charges against the journalist, including working with foreign intelligence, and spreading fake news. He was executed in December.

Zam’s case was cited in a bipartisan resolution by U.S. lawmakers last month that said the journalist was charged with “corruption on Earth” for his reporting.

In recognition of growing threats to press freedom worldwide the resolution—introduced by Senators Marco Rubio, a Republican from Florida, and Bob Menendez, a Democrat from New Jersey—seeks to maintain “the centrality of an independent press to the health of democracy and reaffirms freedom of the press as a priority of the United States in promoting democracy, human rights, and good governance.”