MARION, KANSAS — It was late at night in the Marion County Record newsroom, but reporter and self-described insomniac Deb Gruver was still at work.

Her colleagues long gone, Gruver’s only company was the glow of her computer screen, a clock ticking softly on the wood-paneled wall, and the silence that seems to envelop small towns at night.

At around three in the morning, a motion detector went off, indicating movement in a back room.

Panicked, the 56-year-old called the weekly paper’s publisher and co-owner, Eric Meyer. They agreed the motion detector was probably glitching, but Gruver was still worried.

“I was scared,” she said. “I was shaking.”

So she grabbed a pair of scissors — “the one thing I could think of” — and searched the back room, filled with old printing equipment and newspaper archives.

“I did that because I don’t feel really that safe anymore here,” she told VOA one morning in the paper’s office. “I don’t feel safe in Marion. I’m not sure I ever did, really, but I certainly don’t now.”

Like her colleagues, Gruver has been on edge since local police raided the newsroom on August 11. Not much has felt right since then.

The reporter’s fear may seem outsized for a town whose population measured 1,892 at the last census. But it’s an emotional fallout that the Record staff have been left to contend with.

Since the raid, food and flowers from supporters have been in abundance in the Record newsroom. But so too have anger and paranoia.

The raid itself became emblematic of the crisis facing local media in the United States as the industry faces cuts and attempts to curtail its role as a public watchdog.

“We rely on the media,” said Genelle Belmas, associate professor of media law at the University of Kansas.

“Even though many local newspapers are closing and there’s big news deserts,” she said, “we still rely on it.”

On the morning of the raid, Gruver and her colleague Phyllis Zorn were taking a break in the parking lot, looking at a Facebook post.

In the since-deleted post, says Gruver, business owner Kari Newell said she had kicked out some of the newspaper’s reporters from a political event hosted at her restaurant. Newell said in the post that the newspaper had illegally accessed information about her.

As the reporters chatted, the town’s police, led by Chief Gideon Cody, approached.

Cody handed Gruver a search warrant, and then grabbed her cell phone. The newsroom’s security cameras captured much of what took place next as police seized computers, cell phones, hard drives and other devices.

They also raided the home of the newspaper’s 98-year-old co-owner Joan Meyer, who died the next day. Her son Eric Meyer blames the stress from the incident for her death.

News outlets and press freedom groups promptly denounced the raid as a violation of the First Amendment. But police defended their approach, saying they were responding to an identity theft complaint filed by Newell.

Marion police have not replied to VOA’s multiple emails, calls and visits requesting comment for this story.

Although the search warrant has been withdrawn and seized devices have been returned, Eric Meyer said he still plans to take legal action over the raid — in part to encourage other local outlets to stand up for themselves, too.

“There’s also a lot of people who are pretty easily intimidated, and they need to understand that they shouldn’t put up with this stuff, and that there are people who will support them,” Meyer said.

Gruver, who in late August sued Cody for taking her cellphone during the raid, feels similarly. “They violated our rights, and I won’t ever be the same,” she said.

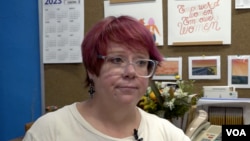

Seated at her desk early one Tuesday, the newspaper’s busiest day of the week, Gruver recounted the raid and its consequences in between the regular peal of newsroom telephones.

Our constitutional rights were violated, and that’s not supposed to happen in our countryDeb Gruver, Reporter, Marion County Record

With her pixie-cut hair dyed pink, and several cans of lemon seltzer on her desk — three empty, the fourth about to be — Gruver wore a shirt with the words “Not Today” emblazoned in big letters.

“Our constitutional rights were violated, and that’s not supposed to happen in our country,” Gruver said, still shaken by the raid. “Journalists are not supposed to have this happen, and it’s been a real eye-opener for me about what journalists in countries such as Russia have to deal with.”

Raids on newsrooms in the United States are rare. Data from the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker show that of over 90 search-and-seizure cases involving journalists since 2017, only around a dozen involved search warrants.

But other forms of suppression aren’t as rare, especially when it comes to local outlets. Analysts say that these newsrooms also often are less likely to have the resources to fight back, and their cases are less likely to garner international attention and support.

“Unfortunately, there’s an atmosphere that’s been created by public officials that the press is the enemy of the people, that the press is working contrary to the public good, when, in fact, the opposite is true,” said Tim Franklin, who heads Northwestern University’s Medill Local News Initiative.

Lawsuits are another tactic that are being used as a form of retaliation against small outlets — like in Wisconsin, where a local outlet reported on the use of an anti-gay slur and is now facing financially devastating lawsuits as a result.

Still, a financial model that hasn’t really worked since the advent of the internet is the most pressing issue.

The United States has lost more than one fourth of its newspapers since 2005 and is set to lose one third by 2025, according to a report by the Local News Initiative. Economic challenges are often to blame for the paper closures, which contribute to so-called news deserts: communities that aren’t regularly covered in the media.

Major corporations have also been buying up and gutting local news outlets at a rate that concerns media advocates.

“Our amount of dailies has shrunk; the weeklies have sometimes combined into more regional papers,” Emily Bradbury, executive director of the Kansas Press Association, told VOA. “That being said, we have been very lucky in Kansas in that we have about 109 print and online-only papers, and we only have 105 counties.”

Among them is the Marion County Record, which is an anomaly in many ways, first and foremost because it exists at all.

“I like being involved in what goes on in the world. I like thinking that I can help people make up their mind, even if they make up their mind a lot differently than I would make up my mind,” Meyer said. “Making sure we have information, keeping that information flowing — extremely important.”

The stakes are high for the Record and other local outlets that remain. Studies show that the fall of local news contributes to a decline in civic engagement and trust in media, as well as the spread of misinformation and disinformation, and a rise in polarization and government corruption.

Marion Vice-Mayor Ruth Herbel, whose home was searched as part of the same case, said Marion “is just a nice, little country town.”

Named after the American revolutionary Francis Marion, it covers less than three square miles and is dotted with small rhinoceros statues and dusty cars, the latter a symptom of drought gripping much of the state.

But in addition to the dizzying heat of the Kansas summer, a level of division has engulfed Marion, between residents who like the newspaper and those who think its coverage is too negative.

“I cannot deny that it’s a well-run paper, that it’s a well-produced paper,” Mike Powers, a Marion resident and former judge, told VOA after a city council meeting. “But I tend to be on the side that feels like it is overly critical.”

Powers, who is running for mayor in Marion, added that he still subscribes to the Record.

But those who dislike the Record are just a vocal minority, several newspaper staffers and residents told VOA.

“If we didn’t have this newspaper, believe me, this community would be so upside down, it would be pathetic,” said Marion resident Darvin Markley.

Still, that criticism from residents is indicative of the forces at play in struggles facing media across the United States, where distrust in media is at an all-time high.

“This is a bigger societal problem. We have a real divergence of opinions on what is fact and what is opinion,” Bradbury said.

In 2022, Gallup measured that 28% of U.S. adults say they do not have very much confidence and 38% have none at all in newspapers, television news and radio.

“What worries me is the willingness of people to disbelieve,” media professor Belmas said.

Zorn, the Record reporter, is familiar with that kind of distrust, she said, because of her dad, who worked in law enforcement and ended his career as a small-town police chief.

“My dad came home nearly every morning or night cursing about reporters,” she said, adding that refrains of “the press is out to get us” were common in their house.

Local journalism doesn't have a demand problem. It has a business model that’s implodedTim Franklin, Northwestern University Medill Local News Initiative

Once Zorn became a reporter and her father started following her work, his view changed. “Because one of the similarities between being in law enforcement and being a reporter is you hold people accountable for what they do,” she said.

But people tend to have more trust in local media than national media, according to Franklin.

“These are people that are in their communities, that they know or that they see at the grocery store or the baseball diamond,” Franklin told VOA. “Local journalism doesn’t have a demand problem. It has a business model that’s imploded.”

As the U.S. expanded West in the country’s early years, said University of Kansas professor Teri Finneman, you needed three things to be considered a town: a church, a bar and a newspaper.

“You knew you were a town when you had a paper,” Finneman said.

So what happens to a town’s identity when there is no paper to cover it?

“A lot of these places are really — I don’t know if I want to say ignored, but they don’t get a lot of attention from state and regional outlets. So who’s left to tell these stories?” said Tim Stauffer, president of the Kansas Press Association and managing editor of the local Kansas newspaper the Iola Register.

Stauffer is the fifth generation of his family to help run the newspaper in Iola, a town of about 5,400.

“Lives here are important,” Stauffer continued. “People matter. Their relationships are unique.”

On Tuesday evenings at the Marion County Record, bellows of “Oh, sh--!” from Meyer are known to ring throughout the newsroom as staff work to finish the paper by their midnight deadline.

The first Tuesday after the raid, police still hadn’t returned the equipment they had seized, so staff labored until five in the morning to finish the paper.

With one hand tied behind their backs, they made it work. The front-page headline proclaimed, “SEIZED … but not silenced.”

“It’s proof that no matter how hard you try to squelch the press, we’ll prevail,” Zorn said. “By God, we printed.”

Editor's Note: The 15th paragraph has been corrected to clarify that Gruver was not at the political event in the restaurant.