Last September, protests erupted across Iran in response to the death of Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish woman who died while in police custody. In the months following Amini's death, authorities arrested dozens of journalists.

By year's end, 62 were behind bars, according to an annual census conducted by the New York-based nonprofit Committee to Protect Journalists, or CPJ.

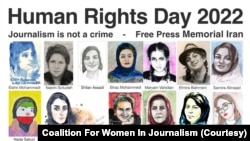

Over the past year, at least 95 journalists have been arrested in Iran. More than 30 of those arrested were women, CPJ data showed.

The numbers tell only part of the story, said Kiran Nazish, founder of the Coalition for Women in Journalism, an organization that protects women and nonbinary journalists.

"What we saw right after last September was an unprecedented number of arrests of women journalists," Nazish told VOA. More concerning, she said, were the reports of women being assaulted before the arrests and while in prison.

"There are physical assaults, there's pulling of the hair, there's beating, there is screaming, there is abusing within the prisons, and at least from three prisoners, we've heard this consistently," said Nazish.

In a letter written from Evin Prison where she is serving a 10-year, nine-month sentence, activist Narges Mohammadi detailed cases of women entering prison covered in bruises. One woman had a fractured cheekbone, another a broken leg.

The full letter was posted to Instagram last month by the nonprofit organization Middle Eastern Matters.

Iran's Mission to the United Nations did not respond to VOA's emailed request for comment.

Earlier this month, journalist Niloofar Maroufian went on a hunger strike while in prison to protest the treatment of women and her own assault by authorities, Agence France-Presse reported.

Maroufian was first arrested last October after she interviewed the father of Mahsa Amini and covered the subsequent protests. Maroufian has been released and rearrested four times in the past 10 months, a pattern of intimidation that sends a message to other journalists, said Nazish.

Many journalists who have been released on bail are banned from leaving the country, working as journalists, posting to social media, or even speaking to friends and family about their experiences in prison.

Nazish recalled a recent conversation she had with a journalist in Iran: "She's out of prison, but that doesn't mean she's safe. That doesn't mean that she feels free," Nazish said. "Because all of these limitations that are put upon journalists," she still feels like she is in prison.

In addition to arrests, journalists and women across Iran have faced an increase of oppression over the past year, according to Negin Shiraghaei, former BBC Persian anchor and founder of the Azadi Network — a nonpartisan foundation aimed at advancing "women, life, freedom" values and elevating Iranian women's voices.

"We shouldn't forget the government has been pushing even more than before and oppressing people," Shiraghaei told VOA. She cited policies that prevent access to reproductive rights and put pressure on women not obeying the mandatory hijab law.

Despite the pressure, women continue to protest, many walking the streets without hijab in defiance of the law. That's the same law for which Amini was arrested.

Iranian journalist Afra Amid, who fled Iran in 2021 for fear of arrest and uses a pen name to protect her identity, said she's maintained a close eye on events in the country, and has watched as the culture has begun to shift, despite the massive crackdown.

Amid recalls walking through Tehran with her shawl around her shoulders as an act of defiance. But the covering was available to pull over her hair if the morality police — agents who patrol the streets to enforce the dress code — confronted her.

Today, she said, she sees videos and photos of women in Iran walking without a hijab or a shawl and when confronted, telling authorities, "It's at home."

"In the last 44 years, it is the first time we're seeing this," Amid told VOA. "We always carried our shawls because there was something — like this fear was hidden somewhere. But now there's no fear."

Amid credits the younger generation of Iranians — members of Gen Z — for their bravery and willingness to stand up for their rights. "This generation, some of them even financially cannot afford to emigrate," said Amid.

"To stay in Iran is their only chance, and they look at everywhere and there is no future. They're like, 'Either I will go and fight and take my future and my present back or I will die, because anyway I'm dying if I continue this life.'"

Though younger Iranians are credited with leading the protest movement, women from all ages and walks of society have joined in and expressed solidarity, said Shiraghaei.

"Different women have lived the same experiences from different parts of the country and that unites them," Shiraghaei told VOA. "So, it doesn't matter if they're old, if they're young, if they're educated or uneducated, there's unity around that pain. The shared pain exists for women."

Both Amid and Shiraghaei are hopeful the movement will lead to more change, however incrementally it might happen.

"I do believe that there is no way to go back," said Shiraghaei. "And I've heard this from a lot of people inside Iran that they say, 'Oh, we're not going to go back to before the 16th of September. For us, there is only one way and that's [for] this government to go away.'

"A year after, still, the movement is really alive. … They know what they want, and they know what they don't want, so one way or another, they're going to create the change."