When Johnnie Yellock enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, he knew his job as a combat controller would frequently put him in harm's way.

“We volunteered in a time of war, we knew exactly what we were up against,” he told VOA. “A lot of our job titles were putting us right on the battlefield. We were ready for that. I was prepared to die for my country.”

Watch: Former president George W. Bush Honors Military Veterans

Although he was prepared, war has a way of changing the best-laid plans. Even Johnnie Yellock’s.

During a deployment to eastern Afghanistan, on July 6, 2011, the vehicle he was traveling in struck an improvised explosive device, or IED.

The force of the blast tore through his body. Although he had to apply a tourniquet to both of his own legs to stop the bleeding, he continued to help his team by calling in the evacuation flight that would lift them to safety and desperately needed medical assistance.

Helpless, but not hopeless

But instead of being relieved, Yellock was frustrated he couldn’t stay in the fight.

“I went from being the tip of the spear on the battlefield to being loaded on a stretcher and carted off the battlefield, completely helpless.”

“The whole family was blown up with Johnnie,” explains his mother, Reagan Yellock, also a U.S. Air Force veteran, "because it is such a traumatic experience for the whole family. I knew it was a process. My first priority was: My son was alive. What do we do? What do we do to get him help? To get him back to us and what the process is going to be.”

Yellock’s encounter with the IED that July day in Afghanistan ultimately ended his military career, and began a rehabilitation effort that continues today.

“My recovery was extensive for sure,” he admits. “I’ve had about 30 surgeries on my legs, in a process called limb salvage, so it’s a huge effort to maintain and keep my legs from amputation. I now have adaptive braces, but aside from all the physical trials of recovery and changing your lifestyle, your life took a detour. The transition of being an active-duty service member to then retiring from the military, it’s a pretty humbling journey.”

While that journey might have taken him off the battlefield, it has put him in an art gallery at the George W. Bush Presidential Museum in Dallas, Texas, where Yellock isn’t just visiting the exhibits. He’s a featured subject.

A salute from Team 43

“That is a very unique email to receive to find out that your prior commander-in-chief has taken and dedicated a lot of his time painting several of us wounded warriors.”

Yellock is a member of Team 43, as in the 43rd President of the United States, George W. Bush, who has focused much of his post-presidential work to helping wounded “warriors” like Johnnie Yellock adjust to civilian life.

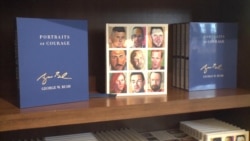

In an exclusive interview with VOA, the former president spoke about Yellock and other veterans who are the inspiration behind his yearlong effort to paint their portraits for an exhibit and book, titled Portraits of Courage: A Commander-in-Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors.

“I know them all,” Bush told VOA. “I’ve ridden bikes with them. I’ve played golf with them. I knew their stories.”

But engaging in sports is one thing. Painting their portraits is quite another.

“How is a person who is agnostic on art for most of his life become a painter?” the former president asked himself.

The answer? The pastime of war-time British prime minister Winston Churchill.

“I happened to read Churchill’s essay, 'Painting as a Pastime.' I’m a big admirer of Winston Churchill, and in essence, I said if this guy can paint, I can paint,” Bush said.

Personal tribute

At first, Bush painted simple objects. Then he transitioned to pets, and moved on to world leaders, until his idea for Portraits of Courage began to take shape more than a year ago.

It’s a tribute to those who Bush, as commander-in-chief of the United States military, was ultimately responsible for sending into harm’s way.

“Rarely do I run into a vet who says, 'You caused this to happen to me,'” Bush told VOA. “These are all volunteers, and I made it perfectly clear we were going to defend the country. And they knew exactly what the stakes were. They go out of their way to make sure that their ole commander-in-chief understands that they understand the sacrifices they made.”

“The trials [Bush] was thrust into ... the decisions he had to make, were difficult ones,” Yellock says. “The humility he shows in recognizing the impact that his decisions made on the lives of so many of us soldiers and our family members - those of my friends that didn’t come home from war, and me coming home wounded. I can speak for all those wounded that we don’t regret going and doing what we did. We would do it again if we had the opportunity.”

It’s that kind of sentiment that kept Bush motivated to take a brush to canvas, day after day.

“So when I’m painting these portraits,” Bush explained, “I’m thinking, what kind of character is it that rather than complain or be full of self-pity, they say, 'Sir, I’d do it again.'”

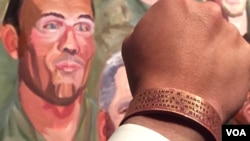

Of the 98 veterans portrayed in Bush’s artwork for the project, Yellock is featured on a four-panel mural, next to several of his friends.

“About 10 minutes ago was the first time I saw my portrait,” he told VOA. “I was just blown away.”

Raising funds to help vets

Bush says he hopes the art speaks for itself, but Portraits of Courage is more than just an exhibit. It’s a fundraiser to help other veterans.

All proceeds from the sale of the Portraits of Courage book, including a more expensive, limited edition signed by the former president, will help fund programs of the George W. Bush Institute’s Military Service Initiative, which aims to help military members transition to civilian life, help veterans find employment if needed, and address ways to treat both the visible and invisible injuries of war.

Johnnie Yellock has both.

He is the recipient of the Bronze Star and Purple Heart, among other military decorations. While he is honored to be a part of the exhibit, just don’t call him a hero.

“Those that don’t come home ... those are the heroes of our time,” he told VOA.

Four of Yellock’s personal heroes have their names engraved on a bracelet he seldom takes off. They were with him when he stood by Bush to announce the opening of the exhibit, and serve as a lasting reminder to Yellock of the ultimate sacrifice from a war that still continues today.

“We knew the risks. We knew that being wounded or dying was a possibility. But we get to come home, we get to catch up with our families, and we’ll forever regard those who have paid this nation’s ultimate sacrifice, as this nation’s true heroes.”

The original paintings of Portraits of Courage: A commander-in-chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors are on display at the Bush Presidential Museum through October.