Mas Yamashita does not remember the moment he and his family left the small apartment or "barn as it was called at the time" where they lived in Oakland, California.

But he vividly recalls where they went: the Tanforan detention facility in San Bruno, California. During World War II, thousands of Japanese-Americans were held in confinement there, while a more permanent internment camp was constructed.

“Really, my childhood memories began in the camp,” Yamashita says. He was 6 years old at the time and is now 82.

He could not understand why U.S. officials "covered up the [train] windows with black paper. I wasn’t sure if they didn’t want us to look out or people to see us from the outside."

"I vividly remember this … We didn’t know what time of the day or night it was," he said.

Yamashita, an American born in California, was one of 120,000 people held in internment camps during the WWII.

Because they could not leave the camp, everything was given to them: housing, food, etc., so "everything that the head of the household was responsible for was taken away from them. They basically lost what they felt was their dignity. They were left with no responsibilities. …It was very, very hard for them to accept."

Using the census

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 that resulted in the detention of Japanese descendants living on the West Coast in 10 recently built camps in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming.

To round up Japanese citizens, the U.S. government secretly used the 1940 census. The census is an official count of the U.S. population taken every ten years. The next census will be 2020.

Though it is illegal to release or use any census information to target a specific population, a pair of researchers found evidence that census officials cooperated with the federal government to identify Japanese Americans.

Historian Margo Anderson of the University of Wisconsin and statistician William Seltzer of Fordham University published a pair of papers in 2000 and 2007 that showed census officials released data as specific as names and addresses to the government.

"We want to emphasize to the public that because of what happened to us, it is now safer to participate in the census without the fear of such action happening again," David Inoue, executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League told VOA.

But Inoue conceded his message may not be enough to override peoples’ fear that the census could still be used against them.

Citizenship question

The Japanese experience takes on new relevance as officials from the U.S. Census Bureau and Commerce Department prepared to answer questions on Capitol Hill Tuesday about the addition of a controversial citizenship question to the 2020 census form.

Asking respondents if they are citizens has not been done since the 1950s.

In addition to gathering statistics about the U.S. population, the census is a tool used to decide the number of representatives each state gets in Congress and how billions of dollars in federal funds are distributed. Critics of a citizenship question say that immigrants will be less likely to respond to census questions if they are confronted with one about citizenship. And that will change how much federal aid their communities get.

The Census Bureau has taken this point of view. According to documents in a New York-led lawsuit, Census officials said in a 1980 case that adding a citizenship question would “‘inevitably jeopardize the overall accuracy of the population count’ by significantly deterring participation in immigrant communities, because of concerns about how the federal government will use citizenship information.”

The White House rejects this and U.S. officials say that asking about citizenship will help enforce the Voting Rights Act by determining who is eligible to vote.

"It is imperative that the data gathered in the census is reliable, given the wide-ranging impacts it will have on U.S. policy. A question on citizenship is a reasonable, commonsense addition to the census," Senator Ted Cruz said in a statement.

But to Yamashita, a citizenship question would be “pretty tragic.”

“You wonder, ‘why do they want to have that information?’ … How can they use that information or if they’re going to use it destructively?” Yamashita said.

Nobody ‘talked about it’

More than 70 years later, it is still painful for Yamashita to talk about the internment experience. His voice broke a few times when he described the time after the family were released from the camp.

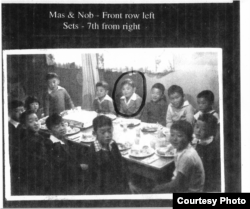

“I lost touch [with the children in the camp] after we left. I had photographs of friends that I used to play with. There’s a picture of one boy. It was in his birthday party.”

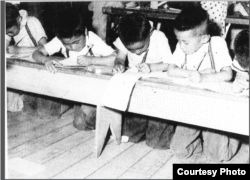

His father wanted him to attend a Japanese school, but he tried to do everything to stay away from his Japanese heritage.

“[There] were a couple of [Japanese schools] in the city, but I lied because I didn’t want to have anything to do with the Japanese,” Yamashita said.

“So I didn’t go. To this day, I don’t speak Japanese. I can’t read or write [in Japanese.] Most of the people I know, my age, don’t speak or write Japanese. I think we all felt the same way in the sense that we didn’t want anything to do with the Japanese culture when we got out,” Yamashita said.

Yamashita recalled fights he had in school, students who made fun of him for being different, and he vividly remembers a teacher who could not pronounce his name.

“I hated my name. … My first year in grammar school after the camp, my class was predominantly Caucasian. There was only one other Asian student in the class and I avoided her. I didn’t talk to her until we reached high school.

Now, after a long career in advertising, he is a volunteer at the Japanese American Museum, to "make up" for all the time he avoided the Japanese community.

“We have to make sure that we record all these stories. We have to keep telling them to future generations. All of my older sisters and brothers are gone and they never got around to do that,” he said.

“After we got out, nobody ever talked about it. Nobody,” he said.