When the heaviest rain of tropical storm Harvey had passed, Kathryn Clark’s west Houston neighborhood had escaped the worst. Then the dams were opened — a decision by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to prevent upstream flooding and potential dam failures by releasing water into Buffalo Bayou, just a few hundred feet from the end of Clark’s street.

When she and her husband returned to survey the damage later that week, they entered their two-story home by kayak in roughly three feet of water. In the kitchen, a snake slithered past.

Nothing like that had happened in the nearly 11 years the Clarks have lived there; it got Kathryn thinking about their long-term plans, including whether to rebuild.

“What if they decide to open the dams again?” she asked. “But if you don’t rebuild, you just walk away, and that is a big loss.”

The Clarks ultimately opted to reconstruct, a process that will take another half-year before they can move back in. Elsewhere in the city, the waiting will be longer.

A sprawling concrete jungle

In early November, Texas Governor Greg Abbott told reporters that Texas will need more than $61 billion in federal aid, to help fund a reconstruction plan that he said would curtail damage from future coastal storms. However, he added, there will be more requests: “This is not a closed book.”

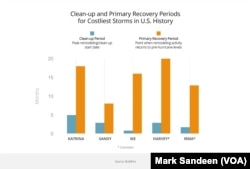

Hurricane Harvey, the costliest storm in U.S. history, will affect Houston for months, and years. Apart from tens of thousands of ongoing home rebuilding projects, civil construction is in the evaluation phase.

“With Katrina, it actually took them 12 years before FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] made their final payment to the city of New Orleans,” said Jeff Nielsen, executive vice president of the Houston Contractors Association. “That’s how long it takes to really test and figure out where all the repairs and where all the damage occurred.”

Houston covers a landmass of 1,600 square kilometers, compared to New Orleans’ 900, and is much more densely populated. The impermeable concrete jungle experienced major runoff during the storm, and that translates to high civil construction costs in roads, bridges, water, sewage and utility lines that are difficult to determine.

WATCH: Post-Harvey Houston: Years Until Recovery, Unknown Costs

Nielsen explains to VOA the immensity of the task.

“You may be driving down the road one day and, all of a sudden — boom — there is a 10-foot sinkhole underneath the road because there is a water line or a sewer line or a storm sewer line that runs underneath that road.

“There is no way to tell that that’s happening without going through and testing each and every line,” Nielsen said.

Waiting, waiting

Rob Hellyer, owner of Premier Remodeling & Construction, says Houston has seen an uptick in inquiries for both flood and nonflood-related projects — good for business, but a challenge for clients.

“A lot of those people come to the realization that ‘If we want to get our project done in the next two or three years, we better get somebody lined up quick,’” Hellyer told VOA.

But industrywide, much of the workforce is dealing with flooding issues of their own, while simultaneously attempting to earn a living.

“It really has disbursed that labor pool that we have been using for all these years,” Hellyer said.

Labor shortages in construction-related jobs have long been a challenge despite competitive wages, according to Nielsen, who describes his field — civil construction — as less-than-glamorous.

“Outside, it’s hot. What could be more fun than pouring hot asphalt on a road?” he asked.

Networking barriers

With construction costs up and waiting periods long, the hands-on rebuilding effort is typically attractive for some lower-wage immigrant communities.

Among the city’s sizable Vietnamese population, though, that’s not exactly the case, said Jannette Diep, executive director of Boat People SOS Houston office (BPSOS), a community organization serving the area’s diaspora population.

“[Vietnamese construction workers] face not only a language barrier but that networking piece, because they’re not intertwined with a lot of the rules and regulations,” Diep said. “‘Well, how do I do the bid; what’s the process?’”

Overwhelmed with paperwork and often discouraged by limited communication skills in English, Diep says many within the industry opt to work only from within their own communities, despite more widespread opportunities across Greater Houston.

The same barriers apply to the Asian diaspora’s individual post-recovery efforts. BPSOS-Houston, according to Diep, remains focused on short-term needs — food, clothing, cleaning supplies — and expects the longer-term recovery to take two to three years, particularly in lower-income neighborhoods.

Love thy neighbor

Loc Ngo, a mother of seven and grandmother from Vietnam, has lived in Houston for 40 years, but speaks little English. In Fatima Village, a tightly knit single-street community of mobile homes — comprising 33 Vietnamese families — she hardly has to.

“They came to fix the home and it cost $11,000, but they’re not finished yet,” she explained, through her son’s translation. “The washer, dryer and refrigerator — I still haven’t bought them yet, and two beds!”

Across the street, the three-generation Le family levels heaps of dirt across a barren lot that’s lined by spare pipes and cinderblocks. They plan to install a new mobile home.

At the front end of the road is the village’s single-story church, baby blue and white, like the sky — the site of services, weddings, funerals and community gatherings.

Victor Ngo, a hardwood floor installer, typically organizes church events. But for now, his attention is turned to completing reconstruction of the altar and securing donations to replace 30 ruined benches.

“At first I had to spend two months to fix up my house, and now I finished my house, and I [have started] to fix up this church,” Ngo said. “So basically, I don’t go out there to work and make money. Not yet.”

In the village, made up largely of elders, Ngo stresses the importance of staying close to home to help with rebuilding, translation, and paperwork, at least for a while longer.

“We stick together as a community to survive,” he said.