The strategic partnership agreement signed by the U.S. and Afghan presidents outlines a continued U.S. commitment to Afghanistan beyond the withdrawal of U.S. combat troops.

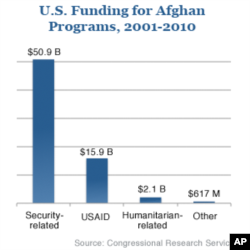

The pact calls for continued expenditures of U.S. funds to train, equip, advise, and sustain the Afghan army and police, known collectively as the Afghan National Security Forces, beyond the planned withdrawal of U.S. combat troops in 2014. It also calls for strengthening Afghan governmental institutions.Much of the U.S. and allied effort in Afghanistan has been security-related. But there is concern among analysts that political development has not kept pace with security assistance. As a result, they say, a weak and corrupt Afghan government may be vulnerable not only to military pressure from insurgents, but political manipulation as well.

Said Tayeb Jawad, former Afghan ambassador to the United States, says the U.S. effort and expenditure toward political development has lagged far behind the buildup of security institutions.

“The transition of the security responsibilities to the Afghan security forces, the transition of the Afghan economy gradually from a contract economy into a private-led economy is taking place in a much better organized and robust way than the political transition,” Jawad said.

The Afghan government structure arose out of the 2001 Bonn Agreement, enacted after the Taliban were driven from power. It calls for a presidential system with a parliament and judiciary. Yet analysts say the government is rife with corruption and unable to enforce its writ in many parts of the country, even with Western backing.

Expressing his personal views, Professor Larry Goodson of the U.S. Army War College says although the Bonn accords put a governmental framework in place, the political development has not moved forward as hoped.

“Although we laid out a kind of timetable and process by which Afghanistan would go through a set of elections and move toward a Western-style democratic system, that just hasn't been rooted very deeply or taken shape every well in Afghanistan compared to the focus on the military and the security sector,” Goodson said.

He said the overarching focus by NATO on security development is to allow Western forces an exit strategy, regardless of the state of Afghan political institutions.

“The focus has been on ANSF development, or what I call the ‘Afghanization’ of the security process or the security forces.” Goodson said. “And if that happens to a standard that the NATO forces are willing to certify, and there is a government in place, then a withdrawal can happen, regardless of whether that government is really functional and able to govern the society in a way that is going to be meaningful.”

In the years since the Bonn accords, Afghanistan has had one chief executive: Hamid Karzai. But his term is up in 2014 - the year U.S. combat forces are due to depart - and according to the constitution, he cannot seek a third term. Analysts say no clear figure has emerged into the spotlight who could take Mr. Karzai’s place. Former senior U.S. diplomat Mike Malinowski, who has wide experience in South Asia, said this is in part because young people are not being systematically groomed for future political office.

“I think there is a disappointing lack of new people coming up, and you see this in a lot of societies,” Malinowski said. “There’s not a lack of educated Afghans. There are very competent Afghans who could function anywhere in the world and have functioned anywhere in the world. But whether they have a resonance among the people who live there and have sacrificed every day, I just don’t know.”

Jawad said what is also lacking among young Afghans is a sense of self-confidence so they can take their place in the system. “A young generation of Afghans are realizing that a lot of things aren’t going right in their country,” Jawad said. “But I still do not see a kind of strong sense of confidence of saying that this is the way to solve it. You hear more of a complaint about the international community or the Afghan government or the warlords or this and that. All of it sometimes, or part of it, is justified. But we need to see a generation that thinks, analyzes, and provides solutions.”

Development of political parties has also flagged. Malinowski said there is a historical mistrust of them because parties were deeply involved in the civil war of the early 1990s, which led to the advent of the Taliban.

“Most Afghans, when they think of parties, they think back to the PDPA (People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan) - the communist group, the Khalqi and the Parcham factions of that - or they think of the tanzims, the parties that were created in Pakistan, by Pakistan, to funnel the Afghan logistic and political resistance,” Malinowski said. “So there’s this distrust of this. Of course, the parties, people belonging to parties, trashed Kabul.”

The United States is in touch with Taliban elements to try to bring them to the negotiating table. But what do they want? Jawad, the ex-Afghan ambassador, says the Taliban might be willing to share power, but will insist on judgeships in a judicial system that is also shaky.

“They’re certainly interested in political power,” Jawad said. “Are they interested in political power-sharing or full power, that’s the question. If there is not a mechanism of monitoring and enforcing negotiation in Afghanistan, they will be happy to share power, come in, and then fight for full dominance.”

Sherard Cowper-Coles is a former British ambassador to Afghanistan and ex-Special Representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan who has long argued for intense negotiations with the Taliban. Cowper-Coles left diplomatic service in 2010 over differences with the government on Afghan policy and wrote a book Cables from Kabul on his experiences. He says a settlement by the Afghan government both with the Taliban and Afghanistan’s neighbors is absolutely key to stabilizing political and governmental institutions.

“We’ve got a constitution which is unworkable, is out of keeping with the grain of Afghan political history and geography,” the ex-British diplomat said. “But above all, we haven’t got a settlement with the enemy, the Taliban, the insurgents. And we haven’t got a settlement among and between Afghanistan’s neighbors. So there will be no peace to keep when our soldiers stop fighting next year. And I’m afraid that that’s rather a bleak outlook.”

Afghanistan is expected to top the agenda at a NATO summit conference in Chicago later this month.