Unlike some central and eastern Europe nations, Poland has not seen a major push for an exit from the European Union in the wake of Brexit, but the country's nationalist movements, whose influence continues to rise, are calling for deep reforms in the EU.

Those calls are being led largely by young people, members of the post-communist freedom generation, whose views are often and paradoxically much more traditionalist and conservative than the older generations that suffered under Nazi and later communist repression.

At a nationalist gathering in Warsaw this week, the memory of communist repression is fresh enough to bring a 79-year-old man to tears.

“What they did to my martyred nation!” he said. “I am sorry I lived times like that. I survived thanks to providence.”

The 20th century was not kind to Poland. Once an ethnically diverse, cosmopolitan society, Nazi occupation all but wiped out its Jewish population. Later, Soviet-style communism repressed debate and assaulted the country's traditional culture.

Poland is and feels a part of Europe, but a rising nationalist movement takes aim at the EU’s push for refugee quotas and LGBT rights, which some Poles feel are a threat to traditional culture.

Debate over EU

One outspoken critic of the European Union is a Janusz Korwin-Mikke, a highly controversial anti-left crusader who serves as a member of the European Parliament.

“In the communist times, members of parliament used to speak about workers’ class struggle, friendship with the Soviet Union and American imperialism. In the European Parliament, you must talk about the fight against global warming, the equality of sexes, about the equality of gender, and homosexuals, and about more democracy. It is exactly the same, but they are much more stupid,” he said.

That stance is rejected by Pawel Kasprzak, who took part in the 1980s Solidarity movement that led to the end of communist rule. He sees association with Europe as Poland’s best guarantee against a return to totalitarianism and its best protection against aggression by Poland’s historical enemy, Russia.

“I’m not for conspiracy theories, but I think part of the last recent change was also due to Russian propaganda and the Internet," he said, referring to elections in October that brought the ruling right-wing Law and Justice Party to power. “I think it’s extremely dangerous and I think we in the West - I’m proud to say we belong to the West - we in the West underestimate the threat.”

Kasprzak and others are campaigning against what they say are the ruling party’s moves to put limits on Poland’s Constitutional Court.

Rebuke from Obama

Poland faces possible EU sanctions unless the government reverses controversial changes it made weakening the court's power to challenge government legislation. The impasse prompted a rebuke from President Barack Obama when the U.S. leader met with his Polish counterpart on the sidelines of last week's NATO summit in the Polish capital.

Younger Poles often have a different view of freedom than their parents.

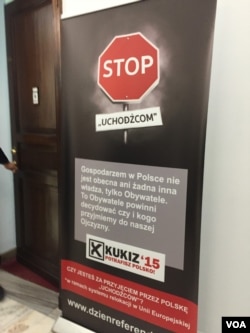

The Kukiz 15 movement, made up largely of young people, is further to the right than the ruling right-wing party. A banner outside its offices in Poland’s parliament building reads: “Stop refugees.”

"We speak with honest language. We do not look at political correctness. We say what we think. We do not dress up simple issues with beautiful words,” said Pawel Szramka, a young Kukiz 15 parliament member.

Runaway capitalism and unemployment in Poland during the 1990s helped shape young people’s thinking and made many cynical about the promises of submitting wholeheartedly to the promises of the western model.

Analysts see a paradox.

“For people who personally experienced the reality of the Second World War, for example, Nazi occupation, the Holocaust, but also the period of dictatorship in Poland, authoritarianism, totalitarianism,” said Rafal Pankowski, a sociologist with the Never Again Association, a Warsaw anti-racism group, “they often tend to cherish civic freedoms more than the young people who don’t have that experience.”

EU exit unlikely

Unlike other parts of Europe, Brexit has not inspired a drive for Poland to leave the European Union, but calls for a reformed, less intrusive EU are growing.

“We do not consider leaving the EU a possibility,” said Malgorzata Gosiewska, a Law and Justice Party lawmaker who says EU mandates on migration and LGBT rights are hampering the debate. “It is also our goal to reach a compromise in Poland. Outside interference makes reaching this compromise difficult,” she said.

For young nationalists, modern western European social liberalism is the enemy.

“I think our culture is a hope for western Europe because western European culture is dying,” said Edyta Luty, 30, at a march attended by scores of young nationalists in Warsaw this week.