Most voters in the United States know that of the country’s two major political parties the Democrats are more liberal on social and economic issues, while the Republicans are more conservative. As party officials gather every four years to select their presidential candidate, they also do the important work of spelling out in detail how they view a variety of domestic and foreign policy issues.

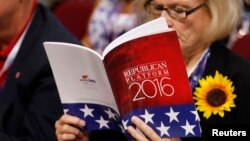

The resulting document is called a platform. Each party uses a similar process by which a committee of select delegates spends a few days debating certain provisions and amendments to come up with a draft that is then voted on during the convention.

Republican analyst Paris Dennard described the platforms as a way to tell the American people and specifically those who identify with the party, what they value and want to promote.

“It’s important to know that and it’s important to have a document to really say this is what I believe, this is what we believe,” he told VOA.

One challenge with the platforms is that because they are spelled out in such detail, they are lengthy reads. The Democratic platform this year runs about 40 pages, while the Republican document is about 60 pages long. Despite the work to produce all that, the average voter will not show up at the local polling place in November having read them.

“It is the hope that every voter before they step into the booth is informed about the issues and the candidates and where they stand on the specific issues before they actually vote,” said David Almacy, a partner at the digital firm Engage who served as internet director under former President George W. Bush.

The specificity does mean that the parties have a chance to attract independents who do not see themselves as either Democrat or Republican.

“There could be something put in that appeals to a group of people that they weren’t expecting,” Dennard said. “It could change the minds of a few votes here and there, and those few can add up.”

Not set in stone

The platforms remain in place for the entire four-year election cycle, and while they serve an important role in grounding each party’s principles around election time, they can also quickly be upstaged by changing national and global events.

In 2012, the Democrats adopted a platform that spoke about ending the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, while a section on battling terrorism focused on al-Qaida. When President Barack Obama leaves office in January 2017, there will be U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. Al-Qaida remains active, but has been eclipsed by the Islamic State group during Obama’s second term.

Similar shifts happened to Bush with the September 11, 2001 terror attacks.

“I remember when President Bush was running for president the first time,” Almacy said. “He ran on the fact that America was not going to be in the business of nation-building. And of course after 9/11, we were faced with new threats that were not foreseen prior to his election and we had to change our strategy.”

In the same way that events may make certain parts of the platform irrelevant, candidates who win the presidency or a seat in Congress are not obligated to use the platform to guide the way they govern.

“The platform is there for the party faithful to say this is what we believe as a party,” Dennard said. “It’s not to be confused as the Trump Doctrine in the sense that this is what he’s going to run on or this is what Speaker Ryan’s agenda is going to be with the next Congress.”

Cat vote

Even if they do not read the platform, voters may still rely on its pieces as a cue when they get in the voting booth. After months of campaigning with rallies and debates and television ads, the choice sometimes comes down to picking the candidate whose name is listed along with the party someone prefers, no matter what.

And despite all the effort put into the platforms and campaigns, sometimes unpredictable factors make all the difference to a voter.

“People vote for different reasons,” Almacy said. “I had one woman tell me that she was voting for President Clinton — this was during the ’96 cycle, I think — because she was a cat owner, and he had cats, and she loved Socks, and that’s why she was voting for him.”

Elizabeth Cherneff contributed to this story.