HONOLULU, HAWAII —

Gabe Baltazar is one of the few Asian Americans to achieve worldwide acclaim as a jazz artist. The versatile musician played saxophone and clarinet with some of the biggest names in jazz.

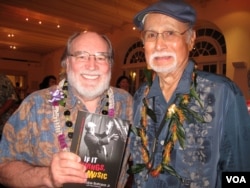

But, in 1969, at the height of his career, Baltazar decided to move back home to Hawaii. Now in his 80s, he's sharing his story in an autobiography called If It Swings, It's Music.

Baltazar had been playing professionally for 15 years when he was asked to join the influential Stan Kenton Orchestra in 1960.

“One of my biggest highlights in Stan's band was being featured on this beautiful standard tune called "Stairway to the Stars," which he liked that tune," he said. "And he thought it would be my signature song. And throughout my career, four years with the band, I was featured on that. And it was just great.”

Baltazar's story is an important chapter in the history of American jazz, says fellow musician Theo Garneau, who co-wrote Baltazar's autobiography.

Garneau calls him one of the pioneering Asian-Americans in jazz, noting that his success came despite the anti-Asian atmosphere of the 1940s and 50s.

“Sometimes people say, well, what difference does it make if he's Asian-American or not?" Garneau said. "I think it's important to remember that there was a lot of exclusion going on in Los Angeles and across the mainland. Asian-Americans were severely discriminated against before and after the second world war, and during the second world war. And this is part of our history, this is part of American history, it's part of Asian-American history.”

Baltazar grew up in Hawaii, the son of a Japanese-American mother and a Filipino father.

“My father was from the Philippines, he was a professional musician," Baltazar said. "And then he came to Hawaii to play with a vaudeville show, to entertain the plantation people, you know, people working in the fields, pineapple and sugarcane fields.”

Gabe Baltazar Sr. encouraged his son to play music and gave him a clarinet when the boy was 12.

Baltazar grew up listening to musicians from the mainland who came to Hawaii in the 1940s to entertain the troops.

"There was Artie Shaw's band. They were stationed in Pearl Harbor, and they performed in Waikiki Beach," he said. "And there, all barbed wire fence on the beach, you know, at that time, because this was World War II. And I used to crawl under the barbed wire and listen to the band.”

Back then, jazz wasn't taught in school in the islands. So Baltazar learned alto saxophone by playing alongside his father in dance bands.

In 1956, Baltazar moved to Los Angeles, where he worked with other Asian-American jazz musicians.

“My first recording was with Paul Togawa, a Japanese American from California who, earlier during World War II, was interned in the internment camp.”

Baltazar gained international recognition with Stan Kenton, then went on to work with Dizzy Gillespie, Cannonball Adderly, Wes Montgomery and others.

But after 13 years in Los Angeles, Baltazar wanted to come home.

“He came back to Hawaii in '69, so the world kind of forgot about him," said Garneau. "And it's just the beauty and the allure of Hawaii and the fact that he was a local guy, that he left when he was on top.”

Over the years, Baltazar became something of a local hero for nurturing many younger musicians. And he's revered by music fans in the islands. These days, Baltazar rarely performs. But he's still eager to share a few tips he's learned along the way.

“I used to play like a thousand notes a minute, you know, during the young days. But now it's, you know, you don't try to get too fancy. You try to get more feeling in your music. So, in other words, you got to get your soul going," he said. "That's what music's all about. And swing, naturally. That's what my book's about, If It Swings, It's Music. That's the name of the book. And it's all in there.”

But, in 1969, at the height of his career, Baltazar decided to move back home to Hawaii. Now in his 80s, he's sharing his story in an autobiography called If It Swings, It's Music.

Baltazar had been playing professionally for 15 years when he was asked to join the influential Stan Kenton Orchestra in 1960.

“One of my biggest highlights in Stan's band was being featured on this beautiful standard tune called "Stairway to the Stars," which he liked that tune," he said. "And he thought it would be my signature song. And throughout my career, four years with the band, I was featured on that. And it was just great.”

Baltazar's story is an important chapter in the history of American jazz, says fellow musician Theo Garneau, who co-wrote Baltazar's autobiography.

Garneau calls him one of the pioneering Asian-Americans in jazz, noting that his success came despite the anti-Asian atmosphere of the 1940s and 50s.

“Sometimes people say, well, what difference does it make if he's Asian-American or not?" Garneau said. "I think it's important to remember that there was a lot of exclusion going on in Los Angeles and across the mainland. Asian-Americans were severely discriminated against before and after the second world war, and during the second world war. And this is part of our history, this is part of American history, it's part of Asian-American history.”

Baltazar grew up in Hawaii, the son of a Japanese-American mother and a Filipino father.

“My father was from the Philippines, he was a professional musician," Baltazar said. "And then he came to Hawaii to play with a vaudeville show, to entertain the plantation people, you know, people working in the fields, pineapple and sugarcane fields.”

Gabe Baltazar Sr. encouraged his son to play music and gave him a clarinet when the boy was 12.

Baltazar grew up listening to musicians from the mainland who came to Hawaii in the 1940s to entertain the troops.

"There was Artie Shaw's band. They were stationed in Pearl Harbor, and they performed in Waikiki Beach," he said. "And there, all barbed wire fence on the beach, you know, at that time, because this was World War II. And I used to crawl under the barbed wire and listen to the band.”

Back then, jazz wasn't taught in school in the islands. So Baltazar learned alto saxophone by playing alongside his father in dance bands.

In 1956, Baltazar moved to Los Angeles, where he worked with other Asian-American jazz musicians.

“My first recording was with Paul Togawa, a Japanese American from California who, earlier during World War II, was interned in the internment camp.”

Baltazar gained international recognition with Stan Kenton, then went on to work with Dizzy Gillespie, Cannonball Adderly, Wes Montgomery and others.

But after 13 years in Los Angeles, Baltazar wanted to come home.

“He came back to Hawaii in '69, so the world kind of forgot about him," said Garneau. "And it's just the beauty and the allure of Hawaii and the fact that he was a local guy, that he left when he was on top.”

Over the years, Baltazar became something of a local hero for nurturing many younger musicians. And he's revered by music fans in the islands. These days, Baltazar rarely performs. But he's still eager to share a few tips he's learned along the way.

“I used to play like a thousand notes a minute, you know, during the young days. But now it's, you know, you don't try to get too fancy. You try to get more feeling in your music. So, in other words, you got to get your soul going," he said. "That's what music's all about. And swing, naturally. That's what my book's about, If It Swings, It's Music. That's the name of the book. And it's all in there.”