A surprising discovery has been made in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease.

An anti-inflammatory drug used to treat menstrual pain completely reversed memory symptoms in mice with Alzheimer's.

The drug, called mefenamic acid, is a so-called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, or NSAID, used to relieve menstrual cramps.

In experiments with mice specially bred to have Alzheimer's symptoms, the rodents predictably developed memory problems over time.

Ten of the Alzheimer's mice were treated for one month with mefenamic acid that was contained in tiny pumps implanted under their skin. Ten other mice with memory difficulties were injected with pumps of a placebo, or inactive substance.

The rodents were placed in maze to train them to get around the obstacles.

In a Skype interview, Mike Daniels, who participated in the research at the University of Manchester in Britain, said, "We tried to train the mice once they had Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's mice are untrainable. They cannot learn that maze."

But the results in the treated mice were stunning.

"What was just amazing is that this drug seemed to render the mice completely normal,” Daniels said. “It's something we haven't really seen before, but there needs to be a lot more work done to really confirm whether this is real.”

Targeting inflammation

The findings were published in the journal Nature Communications. The research was led by David Brough of the University of Manchester.

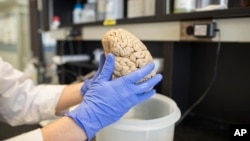

Daniels said brain-imaging shows a lot of harmful inflammation in the brains of Alzheimer's patients.

Researchers believe mefenamic acid targets an inflammatory pathway called NLRP3, reducing inflammation.

Scientist found that no other NSAIDS — including ibuprofen, which is commonly taken for pain — reduced the brain inflammation.

Whether it would work in patients at all stages of Alzheimer's — from people with mild cognitive impairment to those who are severely affected — is difficult to say, according to the study authors.

"Much more work needs to be done until we can say with certainty that it will tackle the disease in humans as mouse models don’t always faithfully replicate the human disease," Brough said.

Co-author Jack Rivers-Auty said, "Maybe, if this was translated into the clinic, we would definitely want to put it into people at the early stages of the disease to try to slow the progress or stop the progress of the disease," Rivers-Auty said.

"Rather than taking the ambitious aim of taking someone who fully has Alzheimer's disease, has all the symptoms — incredible memory loss, incredible cognitive impairment — and trying to reverse those symptoms. That might be very difficult," he added.

Mefenamic acid already has been approved by regulators so, after further testing, it could reach the market relatively quickly as a treatment for Alzheimer's disease.