Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte faces a political test at home as he expects legislators, Cabinet members and the public to accept his controversial proposals for switching allegiance from the country’s historic benefactor the United States to a less familiar China.

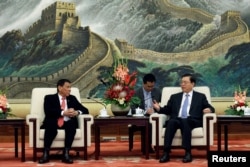

On a state visit to Beijing Thursday, Duterte announced he would “separate” from the United States, his country’s former colonizer and staunchest military ally, and align instead with China, which he called the “only hope” for economic support. Those pledges followed a string of harshly worded anti-U.S., pro-China statements since the tough-talking Duterte took office June 30.

Domestic skepticism could slow or dilute those initiatives, possibly ending in action that covers some of the president's ambitions while incorporating the opinions of a population that remains largely pro-American.

“Our problem with President Duterte is his style. He doesn’t have a ‘group think,’ as I call it, before he makes those pronouncements,” said Ramon Casiple, executive director of the Philippine advocacy group Institute for Political and Electoral Reform. “It’s the other way around.”

Cabinet members are waiting to be briefed on details of what’s next for China and the United States before taking action, analysts say. They say department heads need clarity on how to change ties with Washington and follow up agreements with Beijing.

The four-day Beijing visit produced a Chinese offer of $13.5 billion in economic deals for the largely impoverished Southeast Asian country and an agreement to discuss rights to a contested tract of the resource-rich South China Sea.

“(Duterte) issues a statement and then everybody else among his cabinet who is affected suddenly tries to second guess what he’s really trying to say or modify it,” Casiple said. Some wrongly thought the president would sever formal diplomatic ties with the United States. “At the end of that process, the president himself clarifies what he really means.”

Foreign Affairs Secretary Perfecto Yasay was quoted Monday saying the Philippines would not cut U.S. ties and instead uphold agreements with the United States. He said the Philippines wants a more “independent” foreign policy after years of being largely U.S.-driven.

Officers in the Philippine military may be hard to sway toward China as they have looked to the U.S. for aid since the 1950s to shore up their own forces.

Washington and Manila signed a Mutual Defense Treaty in 1951 obligating each side to support the other if attacked by a third party. Two years ago they reached an Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement aimed at helping Manila stop Chinese vessels from entering a 370-km (200-nautical-mile) exclusive ocean economic zone off the Philippine west coasts.

“Most military officers are graduated from West Point,” said Sean King, senior vice president with the New York political consultancy Park Strategies, in reference to the U.S. Military Academy. Abandoning a defense treaty, he said, would “leave the Philippines open to territorial grabs by China without that defense agreement in place.

“I put those odds of 50-50 for a meaningful break in U.S. relations,” King said.

Philippine lawmakers have been quoted saying they doubt Duterte is serious about his comments in Beijing. At least one worried about depending on Beijing in the context of the South China Sea dispute, which drove Duterte’s predecessor to seek a world court arbitration ruling. In July, a tribunal decided in Manila’s favor.

Other legislators were quoted as suggesting the Philippine government engage China and its rival superpower the United States equally. That foreign policy approach would follow the examples of Indonesia, Myanmar and Vietnam – all of which value China but fear over-dependence on its $11.4.trillion economy.

Senators from the influential minority Liberal Party issued a statement asking for a review of the deals reached in China.

Military aid agreements with the United States require legislative approval in Manila to scrap them. The president can decide how to execute the deals and ask for renegotiation. Duterte has said joint military exercises with the United States earlier this month were the last.

“Definitely there will be opposition. Whether (lawmakers) can block it depends on the nature of the action taken by Duterte,” said Jay Batongbacal, director of the Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea at University of the Philippines. “Right now it’s all just public statements and controversial rhetoric. The Senate can’t act unless it’s an official policy paper or something they can respond to.”

Most Filipinos say they still support U.S. military aid, though some want to give China a chance because it has a record of offering smaller countries investment in factories and infrastructure.

About three quarters of Filipinos place “much trust” in the United States and 22 percent have the same level of trust in China according to a recent survey by the Metro Manila-based research organization Social Weather Stations.

The powerful Catholic Church in the Philippines has kept quiet on Duterte’s foreign policy and is unlikely to voice a view unless the issue touches on human rights, analysts say.

Duterte's shift away from U.S. support risks “alienating” his Cabinet, as department heads try to play down anti-U.S. statements and risks a loss in investment plus defense aid from the United States, said Carl Baker, director of programs with the U.S. think tank CSIS Pacific Forum. Duterte should seek "feedback" from Filipinos, he said.

But it’s “premature” to say what Duterte will ultimately do, Casiple believes. “What we see now is the normalization of relations with China rather than anything else,” he said.