Shortly after 2 p.m. local time Monday, the Iraqi Kurdish news agency Rudaw flashed on its website, "Bashiqa is liberated; Peshmerga in full control." That seemed wildly inaccurate.

From where I stood a couple of kilometers away from one of three frontlines, sniper rounds fired by Islamic State militants whizzed close by, forcing embedded media to retreat. It didn't look like the jihadists had been subdued in the last major town they hold in Iraqi Kurdistan.

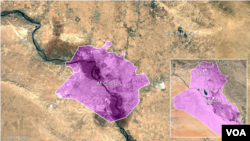

Plumes of black and gray smoke poured from the skyline across the town, 30 kilometers from Mosul. Gunfire could be heard in the center, west and north of the town, as well as periodic ground-shaking thumps. Less than an hour earlier, we had witnessed five suicide car bombs explode near the stadium, roughly in the town center.

Above us, as the news agency celebrated victory, an attack helicopter fired two missiles with a whoosh, followed by a crack in the direction of south Bashiqa, hitting buildings and collapsing them in an orange flash that added another plume of smoke.

This wasn't how the day was meant to have gone for the peshmerga, who conceded there was still much be to done to wrest the town from the militants.

Earlier, peshmerga officers outlined their strategy. The officers aimed to force a breach into the town and then speedily head for the center of Bashiqa, much as U.S. forces did on a grander scale in Baghdad in 2003.

By mid-afternoon, judging by the location of blasts from suicide car bombs, the peshmerga had reached the center of the town. But no one, including peshmerga generals observing the battle, used the word "liberated" for the status of Bashiqa as the sun started to set.

The eve of battle

IEDs (improvised explosive devices), mines, snipers and suicide bombers forced the peshmerga into a much slower pace than had been expected.

Sunday, the Iranian Kurds that I bivouacked with overlooking Bashiqa had been optimistic. As they cleaned weapons and fixed 30-year-old AK-47s, they told me they expected the whole town to fall by 3:00 p.m.

As with most soldiers on the eve of battle, there was a forced nonchalance to them.

"What do you think about the night before a battle," I asked a group of eight fighters with the Revolutionary Khabat Organization of Iranian Kurdistan.

As an old television blared Kurdish music, they nodded in agreement when one of them replied, "I think the hours can't go quickly enough."

They chuckle when I say that what I think about is, "What the hell am I doing here?"

"How will it begin tomorrow?" I ask.

They tell me it will start with airstrikes, and then the big bomb-disposal trucks will lumber into place and start clearing a way through the mines, followed by the assault teams. Their commander for the battle, 41-year-old Bahruz, tells me over breakfast that he expects the fight will be harder than his fighters realize.

He estimated the number of IS to be around 200; the previous day, a peshmerga general suggested more like 60 to 100. "That may seem small, but that is lot with many of them being suicide bombers," he told me. He predicted a lot of casualties.

That echoed the warning a peshmerga officer offered the embedded journalists as we stamped our feet on the chilly eve of battle. "We have a big operation ahead of us," he said. "Urban fighting is very different from fighting in open areas or in the desert. Protect yourself at all times."

Fighters in suicide vests

When it came, airstrikes did not announce the start of battle. There had been a lot of air activity in the skies above Bashiqa as we tried to snatch a few hours of sleep, but no bombs were dropped — possibly because the IS fighters had taken to a pattern of switching locations, alerted to a coming assault by the peshmerga activity in the ridges above them.

The assault started at 7:00 a.m. Progress was rapid in the north, but not other directions. IEDs slowed the column I was with from the east to a snail's pace as bomb-disposal teams cleared the route. The forces encountered seven IS fighters with suicide vests.

But the peshmerga didn't suffer any casualties in the first few hours on the eastern front, according to an Australian medic.

"The last time they tried attacking the town, the peshmerga were gung-ho and they suffered a lot of casualties," he said. "This time caution is paying off."

The advance appeared to speed up and at midday the news was flashed along radios that 11 IS fighters had been killed along with their emir in a massive airstrike in the center of town. He was succeeded by a new emir, who quickly ordered a wave of suicide bombings. The peshmerga also faced highly accurate sniper fire, with two killed Monday.

The peshmerga have shown they can effectively fight IS, but Bashiqa teaches that fanatics who are willing to throw their lives away, and couldn't care less about killing civilians, are horribly difficult to defeat — even by expert soldiers who want to keep their own casualties, and civilian casualties, to a minimum.