Laura Bray is not a doctor but some call her a healer.

Laura Bray is not a pharmacist but she finds drugs for people.

In 2018, Bray’s 9-year-old daughter was diagnosed with cancer. Five months later, the drug she needed to survive, Erwinaze, was in short supply, with a 15-month waiting list.

Her daughter, Abby, sitting in a hospital room asked her, "Does this mean I die?"

Bray and her friends made what she says were “thousands of phone calls” and found the drug in 10 days.

"The story did not end there," Bray told VOA.

"I started asking questions: 'Why did this happen to us? Why isn’t there a buffer supply? Who could fix this?'"

Angels for Change

The answer she found was herself. With her MBA and background as a college business professor, Bray founded Angels for Change a Florida-based organization that is the only patient-centered nonprofit set up to end drug shortages. Bray says patients, hospitals, doctors and pharmacists contact the group from all over the world.

Angels for Change uses its inventory-sharing network, consisting of hospitals and other elements of the supply chain, to find temporary supplies of the drug, starting with the manufacturer.

"How much supply do you have and when are your next releases," Bray says she asks. Sometimes she contacts hospitals with surplus supplies, asking whether they can help a patient in dire need. Her group offers $10,000 to $50,000 manufacturing grants for smaller pharmaceutical companies to produce stocks of drugs vulnerable to shortages.

Ongoing shortages

Drug shortages are not new, according to U.S. Representative Brad Wenstrup, chairman of the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic.

"This is a huge problem and we are late to the game in solving it." The supply chain has been especially fragile with more inexpensive generic injectable drugs which do not hold enough of a profit margin for large pharmaceuticals to continue producing.

"The economics do not make sense for some of these manufacturers," according to Michael Storey who handles medication strategy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, which sees 1.6 million children annually.

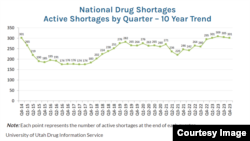

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the issue with delivery interruptions. Still, last year the number of drugs in short supply reached 309, the highest ever.

Push to make US drugs

Allan Coukell, a senior vice president for public policy at Civica Rx, a nonprofit generic drug company created to address drug shortages, appearing at a House Ways and Means Committee hearing on drug shortages in the United States earlier this month testified on how his nonprofit supplied member hospitals with 20 drugs currently in short supply without interruption, emphasizing that Civica Rx maintains "a six-month buffer inventory…to ensure continuity of supply."

Jeromie Ballreich, a Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health professor, urged better transparency with the supply chain, saying, "anticipated changes in demand would allow additional players to think about additional resources and identify risk."

The market has driven prices abnormally low for generic injectables, consistently successful drugs that doctors have prescribed for decades. Consequently, India and China have become huge suppliers of U.S. pharmaceuticals, but quality control issues have resulted in the Federal Drug Administration to halt imports from some Indian companies last year, affecting the drug shortage.

Coukell urged legislators to support domestic manufacturers with incentives, saying "We also emphasize U.S. sourcing whenever possible with Canada and the EU as our next preferences."

Cabinet secretary weighs in

Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, who oversees the Federal Drug Administration told VOA in an exclusive interview that, "Where we can, we should manufacture at home."

Becerra said the FDA needs congressional authority to have "better oversight at the source of the manufacturing" to learn about issues earlier to curtail a drug shortage. The FDA is currently more involved in the retail phase. Becerra also said his agency is "looking at every option … the market is broken when it comes to these medications."

Experts agree the issue is complex and will require a myriad of solutions that could take years. Meanwhile, Laura Bray’s daughter is now thriving in middle school.