This is Part 4 of a 5-part series: Africa's Endangered Peoples

Parts 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

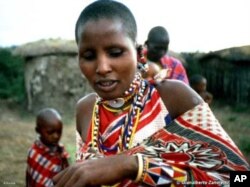

“We’re fighting for our rights, but our culture is dying. Very soon, the world will not know Maasai as we truly were,” says Edward Porokwa, a Maasai and also director of PINGOS – a group of NGOs representing the indigenous people of Tanzania.

Traditionally, the Maasai have survived through cattle alone, with meat and milk being their staples. They herd their animals across the grass plains of northern Tanzania, with some of their ancestral lands being in areas the government has designated as national parks.

The state says the reserves are for animals only. Also, it doesn’t acknowledge the Maasai’s rights to any land, since they’ve never held title deeds. “What has always been difficult for the Maasai is that they don’t recognize formal land ownership. Their tradition is to move from area to area, following the grazing for their animals,” Porokwa explains.

Increasingly, government authorities are ordering the Maasai to leave areas where they’ve survived for hundreds of years. “The Maasai don’t understand this,” says Porokwa. “To them, the land belongs to God and the animals and to people such as them.”

‘Sky high’ cost of investment

What “deeply frustrates” the Maasai, according to the activist, is that the state is increasingly leasing their traditional lands to tourism operators, foreign hunters, private farmers, ranchers and big industry.

“The government is not conserving this land, but exploiting it,” Porokwa maintains. The state acknowledges “generating investment” from various “projects” in northern Tanzania and insists that such profits are used for the good of all Tanzanians.

But Porokwa remains skeptical. “African governments, including Tanzania, are big supporters of foreign investment. It hardly ever matters to them at what cost such investment happens,” he says.

And for the Maasai the cost is “sky high,” says Porokwa, with investment on their lands having several “negative consequences” for them. “One is refusing to allow the Maasai people to access their grazing land and water sources,” he tells VOA.

The indigenous people are also upset that mining is now being allowed on their ancestral lands. “Extractive industries also come with a lot of other negative things, like pollution into (Maasai) water sources,” says Porokwa.

He adds that the presence of tourists benefit a “few” Maasai, “who sing and jump and sell a few trinkets, but mostly the Maasai receive no direct benefit from the presence of these lodges. It’s the government who receives the benefit because the foreigners buy land rights, building rights and business rights from the state.”

Violent evictions

The Loliondo region of northern Tanzania, one of the Maasai’s traditional areas, has been the scene of intense violence in the recent past. Porokwa explains, “The government told the people that they have to move out of that area because it is a conservation area. So the people were evicted by force (by Tanzanian riot police). More than 100 homesteads were burnt down.”

He says many Maasai were injured by “hard weapons, like guns and teargas bombs.”

Survival International, an organization advocating for the rights of indigenous peoples around the world, says it has confirmed the “brutal evictions” of “thousands” of Maasai “to provide safari companies with more access to land for game hunting.”

Porokwa says the Maasai are now “suffering, because (Loliondo) is the only area that has water. The pastoralists need water just like any other human being; as much as their livestock.”

The government denies persecuting the Maasai, but continues to insist they’re “destroying” the environment, especially through overgrazing.

Porokwa vehemently denies this, explaining that the Maasai use a communal land ownership system that always leaves “enough pasture so that it can replenish in time for the next batch of cattle.”

By forcing the Maasai and their animals off their ancestral lands and into “small, concentrated area and not allowing them to roam,” says Porokwa, “that is what leads to overgrazing.”

Resource-based conflict

Lack of water and grazing, says the advocate, brings the Maasai into “deadly conflict” with others, “because everyone is now fighting for few resources.”

The authorities have argued that they’re evicting the Maasai from certain areas precisely to stop such conflict. But the Maasai say this ignores the fact that they, and not the other groups, are the original inhabitants of the grasslands.

Porokwa says, “Government policies are directed towards making the Maasai a sedentary population, which is totally contrary to their tradition. The government only recognizes the rights of settled communities.”

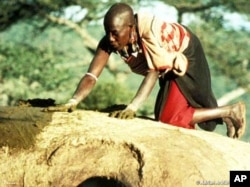

The state is urging the Maasai to become farmers, stressing that their traditional, pastoral way of life is “over.” Porokwa says some Maasai are indeed trying to farm.

“But still they cannot farm (properly) because it is not their tradition; they do not know how to do that. And even if they get to know how to do it, the land (where) they are living is not favorable for farming,” he maintains.

The government says it’s helping the Maasai to “develop” by relocating them to “safer areas” and encouraging them to farm. Porokwa disagrees.

“Helping the people would be bringing water, education and health services close to the Maasai, not building big projects on Maasai land.… But at this point in time, we are facing extinction,” he says.

With the loss of their traditional livelihoods, the Maasai – especially the men – are forced to move to towns and cities. But there, says Porokwa, the “cycle of mass impoverishment” of the Maasai continues.

“They can’t find jobs and even if they do, they earn very little – not enough to send back home to their families,” he comments, adding, “The Maasai men go to the cities as single people, leaving their wives and kids in the villages. At the end of the day many of them get infected with HIV and other diseases, and they spread the diseases when they go back home.”

Hadza people also threatened

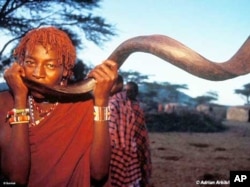

Also in northern Tanzania, another indigenous group is facing “enormous problems,” according to Survival International fieldworker, Fiona Watson. The hunter-gatherer Hadza, who number only 1,500 and speak a unique click language, have lived around Lake Eyasi for centuries.

“Increasingly their land is being invaded by neighboring tribes who are pastoralist people, who herd cattle there. And in the north part of their territory, nearest the Ngorongoro Crater, a lot of people have invaded that land to plant onions, which they sell to an international market,” Watson explains. “So the Hadza are seeing themselves increasingly squeezed and losing a lot of valuable land which they rely on entirely for hunting.”

As in the case of other indigenous peoples throughout Africa, says the researcher, most locals and the government consider traditional groups like the Hadza to be “very primitive.”

Watson says there are “a lot of really racist attitudes” towards hunter-gatherers in Africa. “For example, the Tanzanian government has always wanted to settle the Hadza people. They’re trying to bring them into towns, providing them with education. (But) nobody really sits down and says to the Hadza or other hunter-gatherers, ‘Well what is it that you want? How do you see your future and your development?’”

She says the Hadza not only are “targeted” by people “stealing” their land, but are also victims of “preconceived ideas, of government thinking, ‘Well, we know what’s best for you.’”

Watson says all the Hadza she’s met have insisted that they wish to remain on their land. “They want to live that way of live because it’s a good way of life. The game means everything to them,” she says.

Her NGO wants the Tanzanian government to formally recognize the land rights of hunter-gatherers. Watson says there’s “some encouraging movement” on that front.

“Hadza have told me recently that the government is talking with them about some form of recognition of land title,” she says, adding, “What we would like to see is a proper land rights program that would encompass all the Hadza territory, because that really will be the only way that their land will be protected for future generations.”