Childhood friends and comrades in petty crime, brothers and cousins from families that straddled the French-Belgian border - the suspects and their accomplices in the Brussels and Paris attacks had personal ties that appear to be as binding as their allegiance to the Islamic State group which claimed responsibility for both terrorist strikes.

Arrests in Belgium Friday of half-a-dozen fresh suspects are helping to untangle the complicated network of young men who are believed to be behind the strikes.

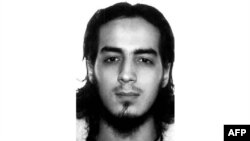

They include Mohamed Abrini, the last known fugitive of the November terrorist attacks in Paris and the self-declared “man in the hat” who was spotted with the Brussels airport suicide bombers last month.

They also include two pairs of brothers, Brahim and Salah Abdeslam, and Khalid and Ibrahim El Bakraoui, who all appear to have been assigned roles as suicide bombers in the two strikes. Three died, while Salah Abdeslam was arrested last month, days before the March 22 Brussels attacks.

Hardly extraordinary, the bonds of blood and neighborhood fit a well-worn model, says criminology professor Alain Bauer, of the Paris-based National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts.

“We all think it’s a terrorist pattern, but it’s just a criminal pattern of a local gang that is trying to protect one of its own,” Bauer says.

Molenbeek ties

Not all the attackers grew up together. Two, Osama Krayem and Mohamed Belkaid had lived in Sweden.

Another, Najim Laachraoui, enrolled at the Free University of Brussels before dropping out after a year. The suspected bomb maker in both attacks, Laachraoui was one of two suicide bombers who killed themselves at the Brussels airport.

Yet many of the assailants and their accomplices had forged ties years before in the seedy Brussels neighborhood of Molenbeek, separated from more elegant parts of Brussels by a gritty canal.

The Abdeslam brothers grew up there. As did Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the suspected ringleader of the Paris attacks.

When Abaaoud sought shelter after the November 13 strikes in the French capital, he turned to his French cousin Hasna Aitboulahcen, who reportedly had a crush on him. Days later, she died with Abaaoud during a shootout with police in the Paris suburb of Saint Denis.

Also in Molenbeek, Salah Abdeslam struck up a childhood friendship with Abrini, the “man in the hat.”

“He’s a great guy, I’ve known him since I was 10,” Abdeslam reportedly told interrogators of his childhood friend.

Abrini joined the gang of future assailants who hung out in Les Beguines bar, run by the Abdeslam brothers. He was known to friends and family as “Brioche” — the name for a sweetish French bread — because of his time working at a pastry shop.

Both Abrini and Salah Abdeslam are suspected to have played important logistical roles in the November Paris attacks. Both were on the run until they were caught near their childhood homes in Brussels. Both may have had orders to blow themselves up - Abdeslam in Paris and Abrini at the Brussels airport - and ultimately opted not to do so, for reasons that are unclear.

Brothers in crime

According to France’s Liberation newspaper Monday, Abrini has told investigators that IS is eyeing this summer’s Euro 2016 football championships in France as its next target. He previously claimed that Paris had been the terrorists’ original target last month, but it was changed to Brussels after Abdeslam’s arrest.

Abrini and Abdeslam are now in prison, and they both had brothers in arms.

Abrini’s younger brother Souleymane Abrini died fighting in Syria in early 2014, after joining a group linked to IS, according to local reports. Souleymane appears to have been the more intense sibling; the two were “like night and day,” one of Abrini’s sisters told France’s RTL broadcaster last year.

In the Abdeslam brotherhood, Salah was the reported leader. Yet Brahim, not Salah, detonated his suicide vest outside a Paris restaurant last November, killing only himself.

By contrast, both the El Bakraoui brothers carried out their apparently assigned tasks. Older brother Brahim, 29, blew himself up in the Maelbeek metro station.

His brother Khalid, 27, was one of the suicide bombers at the Zaventem airport.

Both men had prison records, and ultimately tipped from gangsterism to radical Islam. Turkish officials claim they deported Brahim El Bakraoui in 2015, after he tried to cross into Syria.

Strange case of Abdeslam

“You have hundreds of cases of brotherhoods in the history of crime,” says Bauer, the criminology professor. “One brother may have an influence over the other, and their relationships — especially if they had problems with their family or identity - helps bring them together.”

That was the profile of Said and Cherif Kouachi, who authored the January 15 attacks at the Charlie Hebdo newspaper in Paris. The pair grew up in a French orphanage after the death of their mother, possibly by suicide. They were reportedly inseparable.

For Bauer, the only puzzle among the attackers is Abdeslam.

“His task was to blow himself up and he didn’t do it,” Bauer says. “His task was then to resist arrest, and he did not. And when he was arrested, he did not try to kill himself or the police. So he’s a very strange case.”

After the Paris attacks, Abdeslam was still able to tap his childhood ties. Comrades picked him up from the French capital and drove him to Brussels. They also hid him until his arrest last month.

“He was a member of the family, they were all criminals with him,” Bauer says. “It’s a tribal issue, not a terrorist issue.”