Governments around the world are vowing to chase down the wealthy, powerful and famous who set up offshore bank accounts to hide their assets and possibly evade taxes, the immediate reaction to a massive investigative journalists' report.

“What we see is that it’s very easy for people that want to hide their identity to set up secret shell companies in a variety of jurisdictions. And that’s essentially to hide their connection to the money,” said Maggie Murphy of anti-corruption campaign group Transparency International.

The Kremlin denounced the disclosures, saying they were mostly aimed at Russian President Vladimir Putin, and claiming former U.S. State Department and Central Intelligence Agency officials helped analyze the 11.5 million documents leaked from Panama's Mossack Fonseca law firm.

Putin allegations

The report said Putin associates have funneled nearly $2 billion through offshore accounts over the years.

"This Putinophobia abroad has reached such a point that it is in fact taboo to say something good about Russia or about any actions by Russia or any Russian achievements," Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said.

Governments elsewhere scrambled to start investigations for possible tax evasion, with key political figures left to explain why they had created the offshore accounts named in the report by the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

A reporter for the consortium, Will Fitzgibbon, told VOA's Jim Randle on Monday, "Certainly the examples of illegality or even moral suspicion that we found were in the minority. I think the problem with this offshore system is that when you're creating hundreds of thousands of companies, even if a small percentage of those are using those companies to facilitate corruption or bribery, let alone smuggle drugs or weapons across the world, then that alone in itself is, in the eyes of I think many advocates, reasons to scrutinize the offshore world and potentially to enact reforms."

Pressure to resign

Iceland Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson is under pressure to resign after the documents showed he and his wife, Anna Sigurlaug Palsdottir, bought an offshore company in the British Virgin Islands in 2007.

Gunnlaugsson said the couple has not hidden any assets, but stormed out of an interview with a Swedish public broadcaster when pushed to explain the nature of the investment.

"It's like you are accusing me of something," he said.

Investigation requested

Ukrainian lawmakers demanded parliament investigate allegations that President Petro Poroshenko moved his confectionery company, Roshen, to the British Virgin Islands in August 2014 to avoid taxes at a time when there was a peak in fighting between Kyiv's forces and pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine.

A spokeswoman for British Prime Minister David Cameron declined to comment on whether his family had money in offshore accounts set up by his late father, Ian Cameron. She called it "a private matter."

The Australia Tax Office said it is investigating more than 800 clients of the Panama law firm for possible tax evasion.

One tax official said, "The message is clear: Taxpayers can't rely on these secret arrangements being kept secret, and we will act on any information that is provided to us."

India's Finance Minister Arun Jaitley declared anyone who did not take advantage of a government offer last year to disclose hidden offshore accounts would now find "such adventurism extremely costly."

Investigations opened

Norwegian, Austrian and Swedish authorities started investigations of key banks to determine their role in creating offshore accounts, while France said it would review the taxes of individuals mentioned and assess penalties for unpaid taxes.

French President Francois Hollande called the leaked documents "good news," saying, "investigations will be carried out, cases will be opened and trials will be held."

The U.S. Justice Department said it is reviewing the journalists' report and "takes very seriously all credible allegations of high-level, foreign corruption that might have a link to the United States or the U.S. financial system."

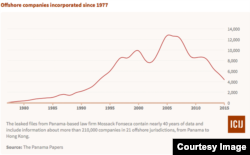

An anonymous source provided the millions of documents involving 214,488 companies and 14,153 clients of the Mossack Fonseca law firm to Germany's Sueddeutsche Zeitung newspaper, which in turn engaged the investigative journalists' group to work on the project.

The Munich-based newspaper said the amount of data it received last year is several times larger than the U.S. diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks in 2010, and the secret intelligence documents given to journalists by Edward Snowden in 2013.

Panama law firm

The law firm at the center of the leak has strongly denied breaking any laws.

“We are a company with almost 40 years in the national market and the international market, and we have never been found guilty of absolutely anything,” said Ramon Fonseca, co-founder of Mossack Fonseca.

But campaigners want further investigations.

“If it is money laundering, if it is sanctions busting, if it is tax evasion that is definitely illegal. One of the things that we have seen is that there are over 23 clients of this company are on international sanctions lists,” said Robert Palmer of Global Witness.

Fonseca told the French news agency AFP that leaking the information to journalists is "a crime, a felony."

"Privacy is a fundamental human right that is being eroded more and more in the modern world. Each person has a right to privacy, whether they are a king or a beggar," the law firm co-founder said.

Putting money in offshore accounts is not necessarily illegal, and can be used to establish legal tax shelters or ease international business deals.

But the report said the documents show banks, law firms and other offshore players often fail to follow legal requirements to make sure their clients are not involved in criminal enterprises, tax dodging or political corruption.

The report covered transactions from 1977 through 2015.

ICIJ says these documents:

- Reveal the offshore holdings of 140 politicians and public officials around the world, including 12 current and former world leaders. Among them are the prime ministers of Iceland and Pakistan, the presidents of Ukraine and Argentina, and the king of Saudi Arabia.

- Include the names of 33 people and companies blacklisted by the U.S. government because of evidence they were involved in wrongdoing, such as doing business with Mexican drug traffickers, terrorist organizations such as Hezbollah, or rogue nations such as North Korea and Iran.

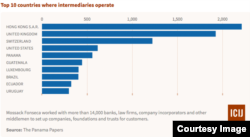

- Show how major banks have driven the creation of hard-to-trace companies in offshore havens. More than 500 banks, their subsidiaries and their branches have created more than 15,000 offshore companies for their customers through Mossack Fonseca.

The Panamanian firm told The Washington Post it follows "both the letter and spirit" of financial laws that vary throughout the world.

It said in nearly 40 years of operation it has never been charged with criminal wrongdoing.

In an interview with VOA Sunday, Michael Hudson, a senior editor at ICIJ, said, "This is really the shadow side of our global economy – the money that flows around mostly unchecked, undetected.

"You can't say in every single case that someone is doing something wrong, or that they're hiding improper practices. But it certainly raises lots of questions about transparency when you have politicians, and especially top leaders of countries, moving their holdings offshore and using offshore entities to obscure what they're doing," Hudson said.

The report lists the British Virgin Islands as the most popular offshore tax haven, with Panama, the Bahamas and the Seychelles next.

ICIJ's report also sheds new light on a 1983 British gold heist that has been called the "crime of the century."

Gold heist

Seven thousand gold bars, cash and diamonds were stolen from the Brink's-Mat warehouse at London's Heathrow Airport, and much of the money was never recovered.

The report said a Mossack Fonseca document shows an official at a company the law firm created 16 months after the robbery was "apparently involved in the management of the money from the robbery.

The company itself has not been used illegally, but it could be the company invested money through the bank accounts and properties that was illegitimately sourced."

The law firm denies it helped conceal the proceeds of the London theft.

Michael Lipin and Henry Ridgwell in London contributed to this story.