Samud Kraja is tasting her first days of freedom. After almost two years in an Israeli prison the 23-year-old sociology student is finally sitting amongst family in her home near Ramallah.

A red Che Guevara flag snaps in the wind at the edge of the family’s courtyard and a six-meter-high poster of Kraja and Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine leader Ahmed Saadat - who remains in jail - hangs from the house next to an even larger Palestinian flag. Chairs fill the courtyard ready to accommodate neighbors and friends coming to welcome Kraja home.

“I had never seen Jerusalem. I wanted to see the city and pray in Al-Aqsa mosque,” Kraja explains.

In October of 2009, then 21-year-old Kraja decided she must see the holy city. The trip, from her home in the village of Saffa to Jerusalem was to take just 15 minutes, via Highway 443 - a major Israeli road that cuts through the West Bank and slices the hills near Saffa.

But Kraja, like most residents of Saffa, was not allowed to access the highway to enter Israel or reach Jerusalem.

Lacking an entry permit, Kraja traveled to the Qalandiya checkpoint - the main exit and entry point between Israel and the West Bank. Once Israeli soldiers there established that Kraja was without permit, they attempted to apprehend her. She says she stabbed one with nail file in self-defense, but for the Israeli army it was an act of aggression and attempt on the soldier’s life.

After over one-and-a-half years of detention she was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Did Israel set killers free?

Under an Egyptian-mediated agreement reached earlier this month, captured Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit was freed in exchange for roughly 1,000 Palestinian prisoners, including Kraja.

On the list of the first 477 prisoners released under the Shalit deal are top Hamas members and many with a history of violent crimes. Yehia Sinwar, considered a founder of Hamas’s military wing, was freed after serving 23 years of the four life sentences he received for his role in the organization that is held responsible for dozens of deadly attacks against Israelis.

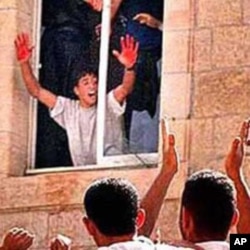

Also among the released are some of the most notorious Palestinian attackers. One of them is the almost iconic Abed al Aziz Salaha, who showed cheering crowds in Ramallah his blood-covered hands after the killing of two Israelis in 2001. The image of Salaha’s bloody palms held out a window became a symbol of terror and the second intifada for many Israelis.

Amna Mona, who was serving a life sentence for luring a 16-year-old Israeli boy to his violent death via a chat room in 2001, is also free. The story of her faked online romance and manipulation of the teenager from Ashkelon still strikes fear in the hearts of many.

“There are many families facing that their son’s murderer is going free,” says Neta Barak, a lawyer working in the pardon department of the Israeli Ministry of Justice. “It’s a very difficult decision made by our government.” Barak explains that an assessment was made of those to be released to judge the risk of repeat offenses.

Some, like Kraja, were put under security arrangements but allowed home. But 200 others, including Salaha and Mona, were deemed too dangerous for the West Bank, and were relocated to Gaza or abroad.

Standards of justice

Sahar Frances is the Director of Addameer Prisoners’ Support and Human Rights Association, a group that monitors the standards of criminality and justice for Palestinians under Israeli occupation in the West Bank. The group also advocates for imprisoned Palestinians, many of whom are tried by military courts.

"Some of these prisoners have spent more than 30 years in jail," says Frances. Of those released last week, some were in prison since before Shalit was born.

After those years away, Frances points out that around 200 of those originally from the West Bank will not be returning home. “The mothers and wives may wait a long time before seeing them,” says Frances.

Kraja had three hearings over the last two years. These hearings were the only time she saw her mother.

“We are just happy to have Samud here,” says her mother Hanan. “I just want her to go back to school and get married.”

Now released, Kraja says she’ll return to university. She hopes to become a social worker.

However, life will not exactly return to normal. Before she was released, explains Kraja, she was required to sign a document promising not engage in political organizations or events for the 18 years that remained in her sentence. She’s also not allowed to leave the area near her village without special permission. Violating these conditions will mean a quick return to jail.

Free but not reunited

Just a 10-minute walk from the Kraja home, on the other side of Saffa, a slightly less joyful mother sits in the front room of her house.

Zahra Falana’s son, Ata Falana, was also among those freed, after serving 20 years of a life sentence, but he is not coming home. He is among the prisoners from the West Bank and East Jerusalem that were relocated to the Gaza Strip.

“I saw him on the television,” says Falana. This might be the only glimpse she gets of her son in the coming years.

“I don’t know how long he will stay in Gaza and I don’t know if I can get the permission to go there,” says Falana, holding a picture of her now 45–year-old son.

Ata Falana’s relocation to Gaza was a solution for a difficult compromise for Israel. Like many of the released prisoners he is responsible for the deaths of Israeli citizens and Israeli officials say experience has taught them many released prisoners will return to terrorist activities.

Gaza is separated from Israel by a tall cement wall and crossing into Israel through the Erez checkpoint requires hard-to-obtain permits and rigorous security checks. Relocation to Gaza makes attacks against Israel by newly released prisoners difficult, but not impossible. For that reason, those considered even more dangerous, were sent to third countries - Turkey, Syria or Qatar.

For example, Walid Anajas, was serving 36 life sentences for his role in bombings at the height of the second Intifada, which killed more than 30 Israelis. He was deemed too dangerous by Israel to stay in the Gaza Strip and was exiled from the Palestinian Territories.

While Hamas agreed to the relocation of these prisoners, those released had no choice. But Israel says it was the only option to preserve security.

“You wouldn’t want to have killers back in a position where they can harm Israelis again,” said a senior Israeli official who asked that his name not be used, pointing to the celebrations across the Gaza Strip that followed the prisoner release. “Gaza is already full of weapons and terrorists.”