Barring any diplomatic surprises, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas intends to make the case for membership before the United Nations this week. However, some analysts say he need not bother – that, in fact, Palestine already is a state, whether a U.N. member or not.

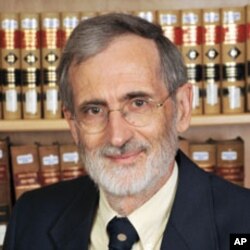

John Quigley, professor of international law at Moritz College of Law, Ohio State University, and author of The Statehood of Palestine: International Law in the Middle East Conflict, argues that Palestine has, in effect, been sovereign since the end of the British Mandate in 1948. Further, he says, Palestine officially declared itself a state in 1988, and when the U.N. responded to that declaration, it was in effect recognizing Palestine.

He cites the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States of 1933, which stipulates that “statehood” is not dependent on recognition by other states. To be considered an official state, an entity must possess a permanent population, defined territory, a government and the capacity to enter into relations with the other states.

Quigley argues that Palestinians meet all of these criteria, therefore it is not even necessary for them to go the U.N. “That is, I think Palestine is a state presently, and that what would be done at the U.N. would simply be a confirmation of that.”

If that’s the case, why is Abbas proceeding with his U.N. bid? “The International Criminal Court,” says Quigley, “would be likely to go ahead with investigating the alleged war crimes…that may have been committed in Palestine’s territory.”

Quigley also argues that there is legal precedent for the General Assembly to override a veto by any member of the Security Council. “There’s a long history on this issue,” he said. “It came up in the 1940s, when the Soviet Union was vetoing. At that time, the United States made a unilateral commitment in the General Assembly that it would never veto an application for admission.”

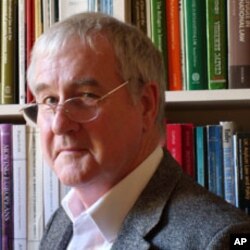

However, other analysts disagree, saying that in the case of Palestine, things are not so cut and dry. Guy S. Goodwin-Gill, Senior Research Fellow at All Souls College, Oxford, says that the Montevideo Convention, while it offers the classic definition of a state, is problematic.

|

Palestinian Statehood Bid Breakdown

|

“That is a mixture of matters of fact, which perhaps were to be determined objectively, and also some matters of appreciational discretion which is where, if you like, the interesting dimension comes in,” he said.

In simpler terms, Goodwin-Gill suggests that the Convention is sufficiently vague that it can be interpreted according to the political objectives of other states.

He also points to the fact that Palestine is under occupation. “That is a qualification of what we look for in every state, which is independence,” he said.

Goodwin-Gill argues that because the borders of Palestinian territory are vague and disputed and the Palestinian Authority does not exercise full sovereignty over its territory, Palestine cannot be considered a state and it will not, until it comes to a final settlement through negotiations with Israel.

He does concede that the conventions are not hard and fast rules. “There are certainly anomalies or entities around the world which do not, on any objective criterion, meet all the requirements of statehood, but which nonetheless are accepted,” Goodwin-Gill said. Such as Monaco, which is a sovereign and independent state, but still linked to France in some matters, such as defense.

Like Quigley, Goodwin-Gill says recognition by the United Nations isn’t necessary in order to be considered a state. He cites the example of Switzerland, which did not become a member of the United Nations “family” until 2002.

He disagrees with his colleague, however, on the matter of whether the General Assembly can override a Security Council veto, saying that the U.N. Charter is quite clear that a state cannot be recognized without a Security Council recommendation. However, that is not to say the General Assembly could not find other political means of enhancing Palestine’s standing, if enough states ask it to do so.

In the end, Goodwin-Gill says, statehood is very much dependent on how you are treated by other countries.