“I have a sword hanging over my head,” says journalist Asad Ali Toor. A vocal critic of Pakistan’s state institutions, Toor was arrested February 26 for, among other charges, running a malicious campaign against government officials. He has pleaded not guilty and is out on bail, awaiting trial.

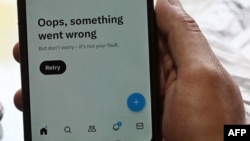

As Pakistan enters a third month of suspension of social media platform X — formerly Twitter — Toor, with nearly 300,000 followers, said disrupting access to the platform is an embarrassment for the state.

“What it has contributed, except controversy and embarrassment to the state of Pakistan, that we are a nuclear armed country, and we are threatened by a social media app? Toor said.

X went down on February 17 in Pakistan, hours after a high-level government official, who later walked back his claim, declared he was involved in large-scale vote manipulation. Pakistan held general elections on February 8, but the results were marred by wide-spread allegations of rigging.

On Wednesday April 17, when Pakistan marked two months of disruption in services, the Interior Ministry told the Islamabad High Court it sought the suspension of X based on information from intelligence agencies.

“The decision to impose a ban on Twitter/X in Pakistan was made in the interest of upholding national security, maintaining public order, and preserving the integrity of our nation," the ministry’s report to the court stated.

In March, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority, or PTA, an independent regulator, revealed to the Sindh High Court that it shut down the platform at the request of the interior ministry. Until then, government officials had denied any ban on the use of X, citing the lack of formal notice.

Pakistanis, including government ministers, have been using X through virtual private networks, or VPNs, raising questions about the practical value of the suspension. Access to the platform is often restored temporarily, causing confusion about the status of the ban.

Criticism vs. fake news

In recent years, Pakistani authorities have blamed social media for an alleged rise in the spread of fake news, and anti-state propaganda.

Since May 9, 2023, when former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s supporters stormed military installations to protest his arrest, the government and the military have lashed out at social media more frequently.

X is a politically active platform in Pakistan, despite a small user base. There, Khan’s diehard supporters and others openly call out the state-backed crackdown on the former prime minister’s political party and criticize the military’s alleged interference in civilian matters.

Toor criticized Pakistan’s top court on social media after it upheld a decision in January to deprive Khan’s party of its electoral symbol, and he says the state labels any news reporting against the establishment as fake news.

“What is the fake news? When people talk about the election? Which everybody says is a very controversial election. You start calling it fake news,” Toor said. “When anybody reports against the establishment, you call it fake news.”

Amber Rahim Shamsi, director of the Karachi-based Center for Excellence in Journalism, said there is some truth to the Pakistani government’s claims of a rise in the spread of misinformation.

Shamsi’s team runs a fact-checking platform called iVerify and recorded spikes in misinformation claims in the lead-up to the February 8 poll. But suspending X, she said, hurts rather than helps.

“It is also hindering the ability of journalists and independent fact checkers to, you know, monitor, trace and correct disinformation, misinformation,” Shamsi said. She is also part of a group of four petitioners challenging the suspension of X in the Sindh High Court.

Most of the false information, she said, is shared via Whatsapp, a popular private messaging app owned by Facebook’s parent company Meta.

Platform vs. user

Justifying the suspension of X, Pakistan’s interior ministry told the high court the platform was not registered locally as a company and ignored requests by the cybercrime wing of the Federal Investigation Agency to remove content maligning the chief justice of Pakistan.

Haroon Baloch, a senior program manager at Bytes for All, a Pakistani think-tank that focuses on information and communication technologies, told VOA that requirement written into the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (2016) is an attempt to influence a company and gain access to users’ data.

“They [Pakistani authorities] wanted data of Pakistani social media users to be housed or hosted through Pakistan and not be hosted outside Pakistan,” Baloch explained.

X’s response

After staying silent on the suspension, X’s Global Government Affairs account finally posted a brief statement Thursday.

“We continue to work with Pakistani Government to understand concerns,” it said.

Baloch said that for media freedom workers, engaging with X to seek support is almost impossible.

“Before [Elon] Musk took over, a team in Singapore was accessible but now there’s no team looking into human rights or policy,” he said.

Last year in March, Musk famously tweeted that emails to Twitter’s press team will automatically get the poop emoji as a response.

Bytes for All research indicates the global content hosting company Akamai may be helping Pakistan implement the ban by rejecting requests from users to connect to X.

VOA asked Akamai if Pakistani authorities had requested help to block users. The company said via email that it was “currently not aware of any such requests.”

Pakistan’s plan

Responding to VOA while interacting with media, Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar said it was the government’s prerogative to take actions “in the best interest of Pakistan.”

“Surely, the country will take its own decision in the light of different reasons, which were the basis of — you know — putting it off [suspending it],” he said.

Taking an apparent swipe at Washington’s efforts to ban TikTok unless it cut ties with its Chinese parent company, Dar said “may I ask those countries that they also have put [a] ban on certain apps … so, one country is OK, and Twitter banned in Pakistan is not OK?”

The Sindh High Court gave the interior ministry a week from April 16 to rescind its letter to suspend X.

Shamsi is not hopeful access will be fully restored soon but said her petition has already had an important victory.

“We have been able to extract information from relevant ministries that the basis of the ban is a letter from the Ministry of Interior, and this was not information publicly available,” she said.

That revelation worries Baloch about the independence of the PTA.

“We can see it’s a clear influence on the regulator,” he said.

Both Shamsi and Toor say they believe the ban is driven by the Pakistani state’s aversion to dissent. They say it is a sign the state is failing to present a strong counter-narrative.

“[The] answer of fake news is not banning any platform,” Toor said as he braces for a possibly prolonged legal battle. “Answer [to] fake news is more credible news.”