Pakistan's decision not to allow a U.S. diplomat from leaving the country for his role in a fatal road accident has fueled tensions between the two countries.

U.S. defense attache, Joseph Emanuel Hall, on Saturday planned to board an American military aircraft at the air force base near Islamabad but was not permitted to do so and returned to the embassy, security officials confirmed to VOA on Sunday.

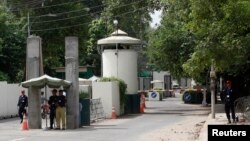

They said several embassy officials had accompanied Hall when he arrived at Nur Khan Air Base where immigration authorities informed him his name is on a government "blacklist" because of the criminal case pending against him.

Pakistani officials said the U.S. military aircraft had arrived in the country from Afghanistan to fly Hall out but went back without him.

A U.S. embassy spokesman declined to comment on the situation with the diplomat nor would he confirm or deny that Hall was prevented from leaving the country.

On April 7, the American defense attache ran a red light in Islamabad, killing a motorcyclist and seriously injuring another person on the bike.

U.S. officials swiftly expressed their "deep sympathy to the family of the deceased and those injured," and pledged to fully cooperate with local authorities in the investigation.

The family of the deceased Ateeq Baig later approached the capital city's high court, demanding Hall be brought to justice.

Washington has rejected the Pakistani demand to withdraw Hall's diplomatic immunity to hold the diplomat accountable for his "criminal" act.

"This level of diplomat, he is not a contractor, has diplomatic immunity. But having said that immunity does not mean that they can flagrantly flout the host country's laws with impunity," Sherry Rehman, leader of the opposition in the Pakistani Senate, told VOA. She has also served as Pakistan's ambassador to the U.S.

Pakistan barred Hall from leaving the country a day after it placed unspecified travel restrictions on American diplomats and withdrew concessions Islamabad had granted to U.S. missions as part of the "war on terror" partnership.

The restrictions went into effect on Friday the same day Washington announced Pakistani diplomats would be required to seek permission five days in advance before traveling more than 40 kilometers from their posts in the United States.

The Pakistani foreign ministry through a formal letter also informed the U.S. embassy its officials would no longer be entitled to special treatment at the airports and their cargo will have to be scanned like that of other passengers.

American diplomats have also been barred from "installing radio communication at residences and safe houses" without prior government permission. They have also been disallowed from using "tinted glass" on vehicles as well as rented transportation and installing non-diplomatic license plates on official vehicles.

Pakistan had granted those concessions to the U.S. after Pakistan joined the "war on terrorism" 17 years ago.

Rehman saw the diplomatic dispute as an "unprecedented stalemate" in relations between Pakistan and the U.S.

"They symbolize a downward spiraling in an already tense relationship. It puts both embassies and missions under a cloud of very unpleasant situation, circumstances and working conditions," Rehman said.

She called for both Pakistan and the U.S. to apply "some serious crisis management diplomacy" to address what Rehman said was a "precipitous and worrying downturn" in the fragile tension-marred bilateral relations.

Pakistan's relations with the U.S. have steadily deteriorated since President Donald Trump announced a new South Asia strategy in August that blamed Islamabad for covertly supporting terrorist groups and the Taliban in neighboring Afghanistan.

While U.S. financial assistance to Islamabad has significantly declined over the yeas, Trump also suspended military aid to the county until Islamabad takes deceive action against terrorists on its soil.

Pakistan rejects the charges and maintains it is being scapegoated for U.S.-led international security failures in Afghanistan.