Pakistan’s government has decided to refer 29 cases of terrorism to military courts for investigation and trial.

The courts were established two years ago after the deadly Taliban attack on a military-run school in Peshawar that claimed the lives of more than 130 children.

Last week Pakistan’s Interior Minister Ahsan Iqbal confirmed the federal cabinet’s decision.

“In the last cabinet meeting, 29 cases were cleared to be forwarded to military courts,” Iqbal told local Pakistani media.

The cabinet decision was taken after Pakistan’s Army Chief Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa sent a letter to Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi expressing his concerns that no terrorism-related case has been referred to the military tribunals this year.

“I have no doubt that the government is serious about implementing the National Action Plan. However, no case has been forwarded to military courts for last many months,” the Army Chief reportedly wrote.

The military is apparently concerned that the lack of referrals may undermine the rhetoric the country adopted after the Peshawar school attack, when it vowed to crack down on militants posing a threat to the country’s national security.

Iqbal said the concerns of the military have been addressed and that the federal cabinet will soon decide whether another 80 terrorism-related cases will be sent to the military courts for trial.

“After this, the interior ministry will not have any more cases pending,” he added.

Number of measures taken

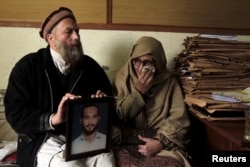

The December 2014 school massacre in Peshawar pushed the country to take a number of measures to address the growing threat of militancy to regional security and Pakistan’s national security.

Following the attack, Pakistan’s National Counter Terrorism Authority (NACTA) was established and the new entity devised a strategy to combat terrorism and militancy in the country. The new strategy known as the National Action Plan proposed a number of steps, including the creation of special courts under the supervision of the country’s military.

In January 2015, Pakistan’s lower house of parliament unanimously amended the constitution and allowed civilians with ties to terrorist organizations to be tried in military courts.

Rights activists are concerned that the establishment of these courts sets dangerous precedents because due process in military courts lacks transparency.

“The politicians felt pressured after the school attack to give their approval despite rights activists’ reluctance and questions regarding the secret courts,” Shama Junejo, a human rights activist said.

“The situation was chaotic and the whole nation was in shock. So, military tribunals were thought to be the best possible solution under the circumstances,” Junejo added.

Fairness concerns

Rights activists are concerned that suspects accused of ties to terrorism are deprived of their rights to a lawyer of their choice and the option to appeal a verdict. The trials are also held without access by the media and the public. There were also reports that judges deciding terrorism-related cases in military courts lacked the required legal qualifications.

According to media reports, the military courts have issued the death penalty to 160 people and 20 people have been executed so far.

Opponents cast doubt at the overall fairness of these military tribunals.

While some experts agree that there are flaws in the military courts, they point to the ineffectiveness of the civil courts, which fail to process terrorism-related cases in a timely fashion.

“Hundreds of thousands of cases remain pending for decades in the civil court system. The hard-core criminals and terrorists cannot get speedy trial and justice through these courts,” Brigadier Said Nazir, a defense and security analyst told VOA.

“Yes, the civil rights activists have raised their concerns on military courts but there’s another side to the picture. These terrorists have killed thousands of innocent people through mass killings, attacks on mosques and on security agencies, which is the biggest human rights violation in itself and deserve no mercy,” Nazir added.

The law passed in 2015, which allowed military courts to operate, expired this January. Pakistan’s parliament extended it with new amendments, including allowing defendants to hire a lawyer of their choice to defend them in the court.

Slippery slope

Analysts like Shama Junejo are concerned that this parallel court system could be abused. She said that despite the few amendments in the existing military courts law, the government must ensure that only terrorists are tried through these courts.

“There are still concerns the military courts do not fit into the national security paradigm. There was a consensus among majority of the civil and human rights activists that only known terrorists’ cases should be referred to these courts. This conflict is still there, in fact it has escalated with time,” Junejo said.

According to local media reports, around 11 military courts are working in Pakistan, including three in Punjab, two in Sindh, three in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and one in Balochistan.

VOA Urdu’s Behjat Gilani contributed to this report.