Washington is becoming increasingly concerned with the mass protests in Pakistan demanding the resignation of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. Questions are being raised about the political stability of the country and how that could impact U.S. interests in the region.

“Washington is watching this protest very carefully, not just because of the inherent domestic threat to the stability in Pakistan, but also because of the regional implications which can be quite troubling and destabilizing,” said Michael Kugelman, senior program associate for South and Southeast Asia at the Woodrow Wilson Center, a Washington-based policy institute.

Thousands of protestors are camped outside country’s parliament in Islamabad in two separate protests.

One protest is led by cricket star turned politician Imran Khan, leader of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party. He is demanding Sharif’s resignation, claiming his election victory last year was tainted by wide-spread electoral fraud.

The other protest, led Dr. Tahirul Qadri of the Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT) party, is demanding a broader “revolution of the system,” according to Claude Rakisits, nonresident senior fellow at the Washington-based Atlantic Council. Specifically, PAT is pushing for sweeping political reforms that will end the hold of wealthy landowners and businessmen on the country's politics.

Sharif has said he will not resign, contending that he must respect his mandate to rule Pakistan until 2018.

While analysts believe the Sharif government is not on the verge of collapsing, they say Washington is concerned about the protests’ impact on Pakistan’s stability, and how that might affect Washington’s anti-terrorism campaign in northern Pakistan and in the planned troop drawdown in neighboring Afghanistan.

“The long term stability of the region depends on Pakistan,” said Cameron Munter, U.S. ambassador to Pakistan from 2010-2012 and currently a professor at Pomona College.

“These protests are likely to draw the Sharif government’s attention and energy away from important long-term issues such as education, health, and public security,” Munter said.

“The long-term issues that will make Pakistan a success, are something America cares about, too,” Munter said. “The longer those long-term issues are neglected, the harder they are going to be [to solve].”

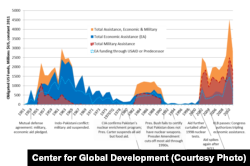

The United States has spent a lot of money to help secure Pakistan’s stability. Between 1951 and 2011, U.S. aid – most of it military assistance - came to almost $67 billion. In 2009, the Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act, commonly known as the Kerry-Lugar-Berman Bill, added another $7.5 billion in civil aid designed mostly bypass the government to assist grassroots social organizations.

U.S. Aid to Pakistan 1951-2011

Impact on Drawdown

A more immediate worry for Washington, according to analysts, is the impact the protests in Islamabad could have on the U.S. drawdown from Afghanistan, which plans to reduce troops in Afghanistan to almost 10,000 by the end of 2014 from a peak of 100,000 and then a complete drawdown by 2016.

The Wilson Center’s Kugelman said U.S. interests in Pakistan were dominated by stability and any incident that could affect the troop drawdown would be of concern to Washington.

Washington is also concerned about the protests strengthening an already powerful military that could deteriorate the situation in Afghanistan before the drawdown, Kugelman said.

“The Pakistani military is a very destabilizing player in Afghanistan because it is known to have links and connections to several militant groups in Afghanistan that launch attacks against U.S. forces and against the Afghan state,” he said.

Madiha Afzal, non-resident fellow at the Brookings Institution, said the protests were also diverting attention away from the Pakistani military operation against militants in North Waziristan, something else that would worry Washington.

“In some sense by making the country unstable in Islamabad, you’re giving the militants space to imagine a weakened Pakistan and stronger footing for themselves,” Afzal said.

Anti-American Rhetoric

Imran Khan, responding to the State Department’s re-affirmation of its backing for Prime Minister Sharif, told his supporters Thursday “while the U.S. was with Sharif, God is with me.”

At the same time, Khan announced he was pulling out of talks with the government until Sharif resigns. In an interview with VOA, Arif Alvi, chief whip for the Khan’s PTI and a member of the negotiating team with the government during the protests, reiterated that the PTI felt the U.S. was backing the Sharif government.

Analysts say Washington is unlikely worried by such statements, which are not new.

“[Khan] is playing on the view in Pakistani public opinion that anyone/anything that the U.S. supports couldn't possibly be in Pakistan's interest,” said Marvin Weinbaum, who served as an analyst on Pakistan and Afghanistan in the State Department and is currently the director of the Center for Pakistan Studies at the Washington-based Middle East Institute.

Afzal, from the Brookings Institute, said Khan’s anti-American rhetoric was not a threat to Washington and was based on a naïve concept that Pakistan must have no interference from any other country, even in a globalized world.

While the statements may not worry Washington, there are concerns about Khan’s political views.

“He’s seen as a right-of-center politician that may sympathize with many of the really hard-line Islamists political parties, and that type of stuff is very worrying for the U.S. government,” said Kugelman, from the Wilson Center.

Limited Priority

Despite the protests and the political impasse, analysts believe the situation in Pakistan is not a top priority for the U.S. government.

Munter, the former U.S. ambassador to Pakistan called Pakistan a resilient country, and “not on the edge of a precipitous decline.”

“There are so many other issues that are going on in the world right now, that are really dominating attention and are worrying Washington a lot more,” said Kugelman.

Despite hopes by protest leaders that crowds would reach hundreds of thousands, Kugelman said much small turnouts have created a sense in Washington that the situation can still be diffused.