As the earth’s climate changes, one tool for understanding its environmental impacts is the study of past climate changes, revealed by layers of sediment scientists take from the sea floor.

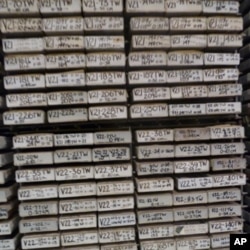

At the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, New York, frozen samples of those sediments are housed in a facility called the Core Repository.

Time capsule

Lamont research professor Maureen Raymo, the director of the Core Repository, slides open a long, narrow drawer from the cabinet. Like thousands of others here, the drawer contains a long, thin cylinder of layered sediment.

It’s a sample extracted from the ocean floor and below. According to Raymo, the cylinder’s distinctive stripes of varied colors and widths are a unique visual record, a sort of vertical time capsule.

“Imagine you are out on a boat, and you could see right through the four kilometers of water that is between you and the bottom. And on the bottom all the little fossils, all the little plankton that die over the years in the water column, their remains settled to the sea floor, just gently settled to the bottom," Raymo says. "And they accumulate, layer by layer by layer, over millions of years. So imagine you just came along and just stuck a big piston tube into the sediment, or took a straw and stuck it into the sediment and pushed it 20 meters down and extracted it, you would have a long core that would essentially be a record of sedimentation going back in time. For geologists, it’s the equivalent of a tape recorder.”

Invaluable resource

Lamont-Doherty oceanographic vessels started collecting these samples more than 50 years ago, at a time when no one was sure what they would be used for.

“The first director, Maurice Ewing, had the sense that these cores had to contain important information and it turns out they do," Raymo says. "They’ve been an invaluable resource in studying past climate change, past ocean circulation, past ocean temperatures, the evolution of life in the ocean in the past, and they are an incredible archive of the evolution of life in the ocean in the past.”

The core samples provide a reliable record partly because the deep ocean is a very peaceful place, compared to the shoreline.

“It’s very far away from the margins where there is a lot of erosional material coming in, where there are lots of waves breaking on the shores and on the continental shelf. Material that settles through the water column just gently layers on the bottom, layer by layer by layer, and it can just be undisturbed for millions of years.”

Vital clues

According to Raymo, the types of species one finds along a length of core reveal vital clues about past environmental changes where the sample was taken. She asks us to imagine a core sample from the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean:

“And you go down your core and you see these kind of sub-polar species, temperate species. Then all of a sudden, you see species that only live in sea ice or next to sea ice. And that tells you that at that location, at that time in the past, sea ice covered that part of the North Atlantic. Because you only see these polar species of plankton. You could go further south and look at a core and see it varying between tropical species and subtropical species, and that’s directly reflective of how the sea surface temperature was changing through time.”

Looking at climate changes of the past helps scientists understand the changes the earth is undergoing today, and is nearly certain to experience at an accelerated rate in the future. Raymo says that when she was a doctoral student in the 1980s, climate change was an esoteric subject few considered relevant.

“And now it’s obviously incredibly relevant. Humans are changing the atmosphere in profound ways by increasing greenhouse gases, and climate is responding to that. The earth is warming. And so there are a lot of questions about how high can CO2 go without causing fairly devastating changes in global climate, either through sea level rise as ice sheets melt, changing precipitation patterns.... And the people in my field, we really look it at as ‘the past is the key to the future’ here.”