The most frequently heard question in the wake of a North Korean attack on a South Korean island is "why?" Those who have devoted their careers to studying North Korea, one of the world's most opaque nations, say it is difficult to get a clear answer. One theory ties the artillery attack last week to efforts to establish the son of leader Kim Jong Il as his successor.

Last Tuesday's shelling of a community on a South Korean island was not the first time North Korea has lashed out at its neighbor since the Korean War in the 1950s.

And, a number of experts on North Korea say, it will not be the last. Indeed, several say South Korea and the United States, which has 25,000 troops in the country, may have to contend with additional military actions by North Korea in the months and years ahead.

Military first

They say it is an inevitable part of the transition of leadership in a country that has declared a "military first" policy for its scant resources.

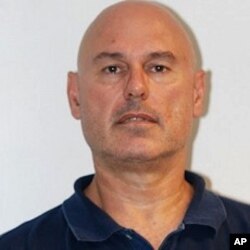

Retired General John Wickham Jr. shares that view. The former U.S. Army Chief of Staff and commander of U.S. forces in South Korea says the North Korean military is critical to a successful leadership transition in Pyongyang.

"It's conceivable that Kim Jong Il has given more independence to the military as a quid pro quo - 'if you will support my initiative here, which you may not like, my efforts to put my son in to follow me," Wickham said.

Seeking support

In the past few months, North Korea's government has established leader Kim Jong Il's son, Kim Jong Un, as his successor. The younger Kim, who is about 28 years old, was made an army general in September, although he has no military background. Some North Korea scholars think that by allowing, or even encouraging, the military to strike out at South Korea, the elder Kim hopes to secure support for the succession.

Although two South Korean civilians and two marines died in the shelling last week, Seoul responded only with a limited amount of return fire, and announcements of new military training with the United States. The training includes naval maneuvers that started Sunday and involve a U.S. aircraft carrier.

More strikes ahead?

While some critics say Seoul and Washington responded too softly, Wickham says they may have no choice but to continue with a restrained response. He expects Pyongyang's military, which is believed to have a few nuclear weapons, to conduct more limited strikes.

"This could be a manifestation of the North Korean military exercising its independence and exercising some of the military prowess that they have to demonstrate that 'we are strong and we are - for our own purposes and for neighboring countries' purposes - capable of defending our interests," Wickham said.

Northeast Asia analyst Daniel Pinkston of the International Crisis Group says there should not be any expectations that influential moderate voices, if there are any in Pyongyang, will be heard.

"[For] any of the military leaders that are on the rise and that have influence in the North Korean government to counsel restraint or to show weakness could result in their political demise. So it's very dangerous at the moment, I think," Pinkston said.

Certainly, the talk out of Pyongyang is tough.

Joint exercises

A North Korea television newscast describes the U.S. aircraft carrier leading the exercises with South Korea as the spearhead aggressive force targeting Pyongyang.

The announcer reads an official statement that calls the maneuvers "nothing but an attempt to stubbornly light the fuse of war by inventing a justification of aggression by whatever means."

Both the U.S. and South Korea are hesitant to push North Korea too far. A miscalculation could lead to a war that leaves, by some estimates, more than a million people dead, and would devastate South Korea's robust economy.

Motivations

Despite Pyongyang's tough talk, other regional analysts theorize North Korea does not realistically expect to defeat South Korea's military or force Washington to back off.

Rather, they say, Pyongyang hopes to bring South Korea down a notch by creating so much uncertainty that its economy is damaged. Or Pyongyang is trying to convince South Korean voters it would be better to replace the current conservative government with one resembling preceding administrations.

The previous two South Korean governments tried to better relations, and gave substantial aid to North Korea, hoping that would persuade Pyongyang to abandon its nuclear programs and peacefully co-exist.

The current government of President Lee Myung-bak, however, has taken a tougher line, cutting off most aid to the impoverished North until it makes progress on its pledges to halt its nuclear weapons programs.