The yet to be confirmed summit between U.S. President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has raised expectations that a major breakthrough in resolving the nuclear crisis on the Korean Peninsula is within reach.

“It is expected that there will be more rapid progress regarding the freezing and dismantling of the North Korean nuclear programs than in the past, as the leaders of the U.S. and North Korea will meet directly this time,” said Cheong Seong-chang, a North Korea analyst at the Sejong Institute in South Korea.

However the process to achieve the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula is complex and will require significant concessions from all involved.

Deal or no deal

On Saturday, Trump said his meeting could fizzle without an agreement or it could result in "the greatest deal for the world" with the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

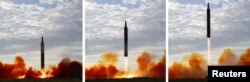

In the short term, Kim could make a seemingly dramatic offer to stop developing its intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capability that directly threatens the U.S., to extend its unilateral freeze on missile and nuclear tests, and even to reduce over time its stockpile of nuclear material.

It is unclear what concessions the U.S. might offer in return. The Trump administration is wary of providing relief and assistance in exchange for promises, given Pyongyang’s record of reneging on past agreements. Washington would likely demand that international inspectors be given access to verify the freeze and dismantling process, before agreeing to reduce economic sanctions.

But to get a significant deal Trump must offer something significant in return.

“In order to make this whole process successful, for which Donald Trump will be responsible, he would have to provide economic concessions,” said Go Myong-Hyun, a North Korea analyst with the Asan Institute for Policy Studies in Seoul.

No preconditions

Both Pyongyang and Washington have already made significant concessions in moderating their conditions for dialogue.

The Kim government has agreed to suspend all missile and nuclear tests during negotiations and discuss the possibility of giving up its nuclear deterrence if their security concerns are assured. Since November of 2017 North Korea has refrained from provocative actions after a two-year period in which it conducted two nuclear tests and accelerated efforts to develop a nuclear-armed ICBM that can target the U.S. mainland.

For his part, Trump has dropped the longstanding U.S. condition that Pyongyang first take concrete measures to end its nuclear program before there can be talks. The Trump administration insists, however, that its “maximum pressure” campaign will remain in place until a deal is reached. U.S. led efforts at the United Nations produced tough sanctions, banning billions of dollars of North Korean exports. The Trump administration also emphasized the threat of U.S. military action, if sanctions were to fail, to increase pressure on Kim to eliminate the nuclear threat.

Delay tactics

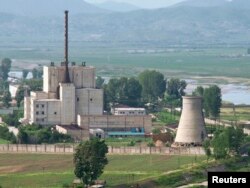

North Korea is estimated to have between 13-30 nuclear weapons, hundreds of medium and long-range missiles, and is continuing to produce enough fissile material for two to three nuclear bombs a year. In addition to its nuclear reactor in Yongbyong, which produces plutonium, North Korea reportedly has hidden uranium enrichment facilities, as well, to produce nuclear fuel.

Even if inspectors were allowed in, it would take possibly years to properly inspect and dismantle the North’s nuclear program. The Kim government strategy may be cooperate enough to reduce sanctions, but to delay and obstruct the denuclearization process for years on end.

“If North Korea can have nuclear weapons for the next 20 years in the process of nuclear disarmament, then North Korea becomes a de facto nuclear state,” said Go with the Asan Institute.

Inter-Korean summit

South Korean President Moon Jae-in, who has worked to facilitate talks between Pyongyang and Washington, will hold a leaders summit with Kim in April, prior to the U.S.-North Korea summit.

The inter-Korean summit is expected to deal with restarting military to military communications, organizing reunions for families separated since the Korean War divided the country, and resuming humanitarian aid.

The Moon administration may also offer Kim economic incentives contingent on denuclearization progress, such as reopening the jointly run Kaesong complex of South Korean manufacturers that employed over 5,000 North Koreans before it was shut down after a 2016 nuclear test.

The Unification Ministry in Seoul said on Monday it would only consider restoring these economic ties once denuclearization progress is made.

“The issue of reopening the Kaesong Industrial Complex can be discussed in a process where the inter-Korean relations and North Korea’s nuclear issue are in progress as a mutually virtuous cycle,” said Baik Tae-hyun, the spokesman for the Ministry of Unification.

Peace treaty

Clarifying North Korea’s stance on denuclearization would be a key long-term goal in the upcoming summit between Trump and Kim. The North Korean leader reportedly said his country would have no reason to retain nuclear weapons if the military threat from the U.S. and its allies is resolved.

But in the past, Pyongyang has called for a permanent peace treaty to the replace the armistice ending the Korean War, which has been used to justify the continued presence of 28,000 American military forces in South Korea.

“When North Korea says it will give up its nuclear weapons and missiles, it is expected that the United States will have to cease all joint South Korea-U.S. military exercises, completely eliminate the international community’s sanctions on North Korea, and to accept establishing diplomatic ties between the U.S. and North Korea,” said Cheong with the Sejong Institute.

Washington and Seoul oppose ending their longstanding military alliance that is defensive in nature in exchange for the North’s denuclearization.

North Korea has still not officially commented on the upcoming summits or responded to recent inquiries from the South Korean government.

"I feel they're approaching this matter with caution and they need time to organize their stance," said the Unification Ministry spokesman.

Lee Yoon-jee contributed to this report from Seoul.