GENEVA —

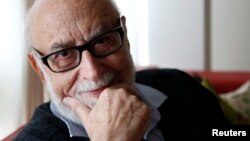

Francois Englert, the Belgian physicist widely tipped to share a Nobel prize this year with Britain's Peter Higgs, said on Tuesday many cosmic mysteries remain despite the discovery of the boson that gave shape to the universe.

And he predicted that new signs of the real makeup of the cosmos, and what might lie beyond, should emerge from 2015 when the world's most powerful research machine - the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN - goes back into operation.

“Things cannot be as simple as our Standard Model,” Englert told Reuters, referring to the draft concept of how the universe works for which the last missing element was provided when the long-sought particle named for Higgs was spotted last year.

“There are so many questions that the model doesn't answer. There must be much, much more. And we look to getting closer to understanding what that is when the data starts emerging from a more powerful LHC,” he said.

Englert, 81, spoke during a visit to CERN, the research center near Geneva where discovery of the boson - which with its linked force field made creation of stars and planets possible after the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago - was made.

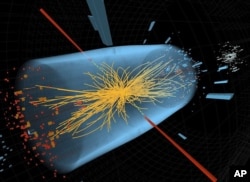

The giant subterranean LHC was shut down in February to be equipped to collide particles at close to the speed of light with twice as much force as during its first three years of operations, crowned with the Higgs' appearance.

Englert's visit, with Belgium's Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo, came amid discussion among scientists on whether the particle should remain tied to the name of Higgs or also bear a reference to Englert and another Belgian physicist Robert Brout.

Three research efforts

The concept of a particle and field that turned flying matter into mass after the primeval explosion that gave birth to the universe emerged in 1964 - the product of three separate research efforts by six physicists in all.

While Higgs, now 83, worked largely alone, Brout - who died in 2011 - and Englert combined their investigations in Belgium while another team - two Americans, Gerald Guralnik and Carl Hagen and Briton Tom Kibble - worked on the idea in London.

Brout and Englert published a paper on their research at the end of August 1964, and Higgs of the University of Edinburgh issued his own six weeks later, followed by Guralnik, Hagen and Kibble a month after that.

But as interest grew in the idea of what was initially called a “scalar” field and boson, the concept became popularly associated with Higgs. Exactly how this happened has never become clear, although there are several theories.

In Belgium it was dubbed the “Brout-Englert-Higgs” or BEH mechanism, a term used by Englert in a short speech to CERN researchers and students on Tuesday. Belgian newspapers have championed the idea of renaming it that way.

Others, including Hagen himself, have insisted that the work of his London team which was based at the British capital's Imperial College, should be recognized.

The issue has gained spice because it is likely that the Nobel committee will award its annual physics prize this autumn for discovery of the boson - and such an honor can, under current rules, go to no more than three living people.

CERN, and its U.S. counterpart Fermilab near Chicago, decline to take a position, either on the prize or a name change. “One thing is clear, the Nobel people have a helluva problem to resolve,” said one senior CERN official.

And he predicted that new signs of the real makeup of the cosmos, and what might lie beyond, should emerge from 2015 when the world's most powerful research machine - the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN - goes back into operation.

“Things cannot be as simple as our Standard Model,” Englert told Reuters, referring to the draft concept of how the universe works for which the last missing element was provided when the long-sought particle named for Higgs was spotted last year.

“There are so many questions that the model doesn't answer. There must be much, much more. And we look to getting closer to understanding what that is when the data starts emerging from a more powerful LHC,” he said.

Englert, 81, spoke during a visit to CERN, the research center near Geneva where discovery of the boson - which with its linked force field made creation of stars and planets possible after the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago - was made.

The giant subterranean LHC was shut down in February to be equipped to collide particles at close to the speed of light with twice as much force as during its first three years of operations, crowned with the Higgs' appearance.

Englert's visit, with Belgium's Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo, came amid discussion among scientists on whether the particle should remain tied to the name of Higgs or also bear a reference to Englert and another Belgian physicist Robert Brout.

Three research efforts

The concept of a particle and field that turned flying matter into mass after the primeval explosion that gave birth to the universe emerged in 1964 - the product of three separate research efforts by six physicists in all.

While Higgs, now 83, worked largely alone, Brout - who died in 2011 - and Englert combined their investigations in Belgium while another team - two Americans, Gerald Guralnik and Carl Hagen and Briton Tom Kibble - worked on the idea in London.

Brout and Englert published a paper on their research at the end of August 1964, and Higgs of the University of Edinburgh issued his own six weeks later, followed by Guralnik, Hagen and Kibble a month after that.

But as interest grew in the idea of what was initially called a “scalar” field and boson, the concept became popularly associated with Higgs. Exactly how this happened has never become clear, although there are several theories.

In Belgium it was dubbed the “Brout-Englert-Higgs” or BEH mechanism, a term used by Englert in a short speech to CERN researchers and students on Tuesday. Belgian newspapers have championed the idea of renaming it that way.

Others, including Hagen himself, have insisted that the work of his London team which was based at the British capital's Imperial College, should be recognized.

The issue has gained spice because it is likely that the Nobel committee will award its annual physics prize this autumn for discovery of the boson - and such an honor can, under current rules, go to no more than three living people.

CERN, and its U.S. counterpart Fermilab near Chicago, decline to take a position, either on the prize or a name change. “One thing is clear, the Nobel people have a helluva problem to resolve,” said one senior CERN official.