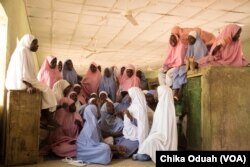

The students of the Government Girls Science and Technology secondary school stand under the gaze of the morning sun, belting out the national anthem. "…To serve with heart and mind, one nation bound in freedom, peace and unity," they sing in unison.

It’s Monday, May 7, the first time in nearly three months these students have sung the anthem together on their school grounds. On February 19, members of the extremist sect Boko Haram kidnapped 109 students from the school. A month later, the insurgents returned the girls, minus about five who died and Leah Sharibu.

Despite their relief, many of the parents are grappling with tough choices about whether to allow their daughters to go back to the Dapchi school or to even resume Western-styled education.

On April 30, the government of Yobe State, where Dapchi is located, mandated the school to re-open. But a week later, fewer than 220 of the school’s more than 900 students showed up.

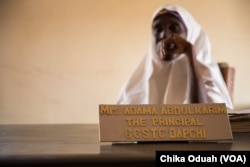

"The reason, we can assume or we can suspect, [was that] the parents were afraid to send down their children or the children were also afraid to come back," the school principal, Adama Abdulkarim, told VOA.

Fear lingers on campus

On the first day back, the students were visibly fearful, walking in groups across the campus from the dorms to their classrooms. Many of the students who came back are traumatized by their monthlong captivity with Boko Haram members.

"They snapped our photos and told us not to return to school, but I came back because I want to learn," said a 17-year-old student who asked for VOA to only use her first name, Maryam.

"I want Western education to improve my future. I came back to this school because I don’t want to change my environment. I have already started school here and I want to finish here. Boko Haram told us that if we go back to school, they will come back to kidnap us and kill us ... but they didn’t tell us exactly when they will come back.”

Mohammed Lamin, the Yobe State education commissioner, said students must be resilient because other attacked schools in the area have resumed.

"Life has to continue. The students will have to learn, they have to study,” he told VOA.

Expectations, threats keep girls out of school

Female students in many parts of Nigeria face unique challenges that often hinder their educational ambitions, including cultural norms that expect females to marry by a certain age.

In addition, Boko Haram’s violent campaign often targets girls. When the insurgents returned the Dapchi students in March, they told the parents that "boko" (slang for books, which refers to Western education) is "haram" (sinful), so they should not return their daughters back to school.

“They believe that girls are weaker than the boys,” said Garba Haruna, whose daughter was among the abducted and returned Dapchi schoolgirls.

Western education in northeastern Nigeria has taken a blow since the insurgency began in 2009. Nearly 2,300 teachers have been killed and 19,000 displaced, and almost 1,400 schools destroyed. Last year, the U.N. Children’s Agency said the violence in the region forced more than 57 percent of schools in Borno State to close, leaving about 3 million children without an education as the 2017-18 school year began.

A multimillion dollar, UNICEF-supported Safe Schools Initiative, launched in the wake of the 2014 abduction of the Chibok girls, is supposed to make schools in northeastern Nigeria more conducive to learning by training teachers on security and providing clean water, among other measures.

In Dapchi, it was only after the February abductions that UNICEF came in, handing out backpacks and school supplies to the students. Soldiers have been posted at the main gate, while local vigilante and civil defense forces stand at the second gate.

The parents of the Dapchi schoolgirls say these measures are helpful. They’ve been meeting to discuss the security situation and have opted to defy Boko Haram’s demand to keep girls out of school.

“We have to fight it. We have to fight it. They cannot beat us and they can never win because we must see that we send them back to school. Let them go,” Haruna said.

The one left behind

It’s a different story for Rebecca Sharibu, whose 15-year-old daughter Leah is the sole Dapchi schoolgirl whom Boko Haram did not release, reportedly because she refused to convert to Islam. Sharibu and her son look at Leah in a family photo.

"When my daughter comes back, I will not allow her to go to that school again. No any government come for us and help us or tell us anything about Leah," Sharibu said, speaking in Nigerian pidgin slang English.

These days, Rebecca often finds herself going into her daughter’s bedroom to cry.

Across the street from the Sharibus' home, Leah’s classmates are taking a huge risk simply by going to school.