When Doundou Chefou first took up arms as a youth a decade ago, it was for the same reason as many other ethnic Fulani herders along the Niger-Mali border: to protect his livestock.

He had nothing against the Republic of Niger, let alone the United States of America. His quarrel was with rival Tuareg cattle raiders.

Yet on Oct. 4 this year, he led dozens of militants allied to Islamic State in a deadly assault against allied U.S.-Niger forces, killing four soldiers from each nation and demonstrating how dangerous the West’s mission in the Sahel has become.

The incident sparked calls in Washington for public hearings into the presence of U.S. troops. A Pentagon probe is to be completed in January.

Who is Doundou Chefou?

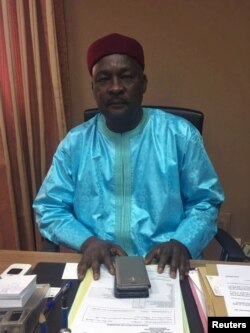

Asked by Reuters to talk about Chefou, Nigerien Defense Minister Kalla Mountari’s face fell.

“He is a terrorist, a bandit, someone who intends to harm to Niger,” he said at his office in the Nigerien capital Niamey earlier this month.

“We are tracking him, we are seeking him out, and if he ever sets foot in Niger again he will be neutralized.”

Like most gunmen in so-called Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, which operates along the sand-swept borderlands where Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso meet, Chefou used to be an ordinary Fulani pastoralist with little interest in jihad, several government sources with knowledge of the matter said.

The transition of Chefou and men like him from vigilantes protecting their cows to jihadists capable of carrying out complex attacks is a story Western powers would do well to heed, as their pursuit of violent extremism in West Africa becomes ever more enmeshed in long-standing ethnic and clan conflicts.

For now, analysts say the local IS affiliate remains small, at fewer than 80 fighters. But that was also the case at first with al-Qaida-linked factions before they tapped into local grievances to expand their influence in Mali in 2012.

The United Nations this week released a report showing how IS in northern Somalia has grown to around 200 fighters from just a few dozen last year.

The U.S. military has ramped up its presence in Niger, and other neighboring countries, in recent years as it fears poverty, corruption and weak states mean the region is ripe for the spread of extremist groups.

Genesis of a jihad

For centuries the Tuareg and Fulani have lived as nomads herding animals and trading — Tuareg mostly across the dunes and oases of the Sahara, and the Fulani mostly in the Sahel, a vast band of semi-arid scrubland that stretches from Senegal to Sudan beneath it.

Some have managed to become relatively wealthy, accumulating vast herds. But they have always stayed separate from the modern nation-states that have formed around them.

Though they largely lived peacefully side-by-side, arguments occasionally flared, usually over scarce watering points. A steady increase in the availability of automatic weapons over the years has made the rivalry ever more deadly.

A turning point was the Western-backed ouster of Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi in 2011. With his demise, many Tuareg from the region who had fought as mercenaries for Gadhafi returned home, bringing with them the contents of Libya’s looted armories.

Some of the returnees launched a rebellion in Mali to try to create a breakaway Tuareg state in the desert north, a movement that was soon hijacked by al-Qaida-linked jihadists who had been operating in Mali for years.

Until then, Islamists in Mali had been recruiting and raising funds through kidnapping. In 2012, they swept across northern Mali, seizing key towns and prompting a French intervention that pushed them back in 2013.

Turning point in 2013

Amid the violence and chaos, some of the Tuareg turned their guns on their rivals from other ethnic groups like the Fulani, who then went to the Islamists for arms and training.

In November 2013, a young Nigerien Fulani had a row with a Tuareg chief over money. The old man thrashed him and chased him away, recalls Boubacar Diallo, head of an association for Fulani livestock breeders along the Mali border, who now lives in Niamey.

The youth came back armed with an AK-47, killed the chief and wounded his wife, then fled. The victim happened to be the uncle of a powerful Malian warlord.

Over the next week, heavily armed Tuareg slaughtered 46 Fulani in revenge attacks along the Mali-Niger border.

The incident was bloodiest attack on record in the area, said Diallo, who has documented dozens of attacks by Tuareg raiders that have killed hundreds of people and led to thousands of cows and hundreds of camels being stolen.

“That was a point when the Fulani in that area realized they needed more weapons to defend themselves,” said Diallo, who has represented them in talks aimed at easing communal tensions.

The crimes were almost never investigated by police, admits a Niamey-based law enforcement official with knowledge of them.

“The Tuareg were armed and were pillaging the Fulani’s cattle,” Niger Interior Minister Mohamed Bazoum told Reuters. “The Fulani felt obliged to arm themselves.”

‘Injustice, exclusion and self-defense’

Gandou Zakaria, a researcher of mixed Tuareg-Fulani heritage in the faculty of law at Niamey University, has spent years studying why youths turned to jihad.

“Religious belief was at the bottom of their list of concerns,” he told Reuters. Instead, local grievances were the main driving force.

Whereas Tuareg in Mali and Niger have dreamed of and sometimes fought for an independent state, Fulani have generally been more pre-occupied by concerns over the security of their community and the herds they depend on.

“For the Fulani, it was a sense of injustice, of exclusion, of discrimination, and a need for self-defense,” Zakaria said.

One militant who proved particularly good at tapping into this dissatisfaction was Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, an Arabic-speaking north African, several law enforcement sources said.

Al-Sahrawi recruited dozens of Fulani into the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA), which was loosely allied to al-Qaida in the region and controlled Gao and the area to the Niger border in 2012.

After French forces in 2013 scattered Islamists from the Malian towns they controlled, al-Sahrawi was briefly allied with Mokhtar Belmokhtar, an al-Qaida veteran.

Today, al-Sahrawi is the face of Islamic State in the region.

“There was something in his discourse that spoke to the youth, that appealed to their sense of injustice,” a Niger government official said of al-Sahrawi.

Two diplomatic sources said there are signs al-Sahrawi has received financial backing from IS central in Iraq and Syria.

Enter Chefou

How Chefou ended up being one of a handful of al-Sahrawi’s lieutenants is unclear. The government source said he was brought to him by a senior officer, also Fulani, known as Petit Chapori.

Like many Fulani youth toughened by life on the Sahel, Chefou was often in and out of jail for possession of weapons or involvement in localized violence that ended in deals struck between communities, the government official said.

Yet Diallo, who met Chefou several times, said he was “very calm, very gentle. I was surprised when he became a militia leader.”

U.S. and Nigerien sources differ on the nature of the fatal mission of Oct 4. Nigeriens say it was to go after Chefou; U.S. officials say it was reconnaissance mission.

One vehicle lost by the U.S. forces was supplied by the CIA and kitted with surveillance equipment, U.S. media reported. A surveillance drone monitored the battle with a live feed.

The Fulani men, mounted on motorbikes, were armed with the assault rifles they first acquired to look after their cows.