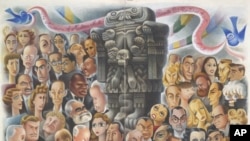

A new exhibit in New York explores the city's long history of cultural and political connections with Spain and Latin America - ties that have affected virtually every aspect of the city's development.

Whether it's the bilingual signs, the ever-present corner bodega grocery stores, or just the spicy rhythms of life in the Big Apple, it's hard to walk down a street in New York City and not sense its Latino flavor.

Marci Reavin is the curator at "Nueva York," a new exhibit on the subject mounted jointly by the Museo del Bario and the New York Historical Society. She says the roots of this influence go back to the 16th and 17th centuries, when the Spanish Empire controlled a swath of land extending from Central South America north through the Caribbean and into North America, from Florida to California.

"So some of the objects we have in the show are the kinds of things that would have been taken from Spanish treasure ships," says Reavin, "like a 16th century bar of silver or the beautiful piece of fabric which shows the red dye that was called 'cochenille.'"

Cochenille is the rare and beautiful scarlet dye made from South American insects. Europeans used it to make its finest royal, clerical and military cloth. It's just one of the New World's riches that imperial Spain exploited. But by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, that empire was beginning to weaken from a series of financially ruinous European wars, the cost of supplying and fortifying their outposts in the Americas, piracy and other factors.

The Spanish Empire was especially challenged during the 1850s, as the United States - with New York as its financial capital - sought to expand its influence south to Cuba, Puerto Rico, northern South America and other lands claimed by the Spanish monarchs.

"But they are also challenged by Puerto Ricans and Cubans who live in New York and are running the liberation struggles out of New York with the goal of freeing Cuba and Puerto Rico from their Spanish imperial masters," says Reavin. "New York is a free city. We have political freedom here. So revolutionaries from all over the world can meet here and plan for revolution in their home country. And they do that in New York during the 1850s and 60s and all the way up to the 1890s when the final war for Cuban liberation starts."

Other trends would couple the destinies of Latin America and New York, as Wall Street investment capital flowed south and raw Latin American goods and produce like tobacco, silver and sugar flowed to northern factories, where they were made into consumer export products. Nueva York historian Mike Wallace says that by the late 1880s, the metropolis was the sugar refining capital of the world.

"So New York, in an odd way, becomes a kind of second capital of Latin America," says Wallace. "And it's a place where many Latin Americans come to get an education, to see the wonders of modernity, to glimpse the future."

Wallace adds that during the early to mid 20th century, Latin rhythms became an important part of American popular culture. Latin American Nueva Yorkers like Machito, for example, teamed up with African American jazzmen to create new musical hybrids.

And out of this comes Afro-Latin jazz which eventually develops into salsa.

"Salsa people tend to think it is coming out of Latin America. But no. It's coming out of Latin Americans who come to New York City, interact with both blacks and Puerto Ricans and Cubans who are here already and their music is picked up by the music industry," says Wallace. "And you get this incredible dynamism that explodes in the 60s and 70s into salsa, an international phenomenon."

Latino immigration skyrocketed following World War II. Between 1945 and 1965, 800,000 Puerto Ricans came to New York. During the 1960s and 70s, hundreds of thousands of Dominicans arrived following the death of the dictator Rafael Trujillo and the escalating U.S. intervention in Dominican political affairs.

Ric Burns, who made a documentary film about postwar Latino New York for the exhibit, says that these newcomers could keep in close touch with their homelands in ways earlier generations could not.

"This is a telephone and airplane migration. People can call home," says Burns. "They are hours from home. It's a very modern change."

Mexicans are the latest comers in Latino New York. In 1984, there were 40,000 Mexicans here. Today, there are a half million. According to Burns, New Yorkers experience this change every day.

"So it's food. It's culture. It's dance. It's music," says Burns. "And what's really amazing is that all those things are mixing it up here. So although they are coming from Latin America and the Caribbean, this Pan Latino identity is an absolutely homegrown American product."

Indeed, as the Nueva York exhibit shows, New York is a hybrid mix, as immigrants from hundreds of countries each add their own flavor to urban life, and continue to change the meaning of the word, "American."