Today in East Harlem, there is a diamond.

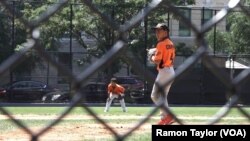

Along two of the diamond's sides, a championship baseball team stands in all its gear. The players, each with a hand to heart and baseball cap removed, look 168 feet in the distance to an American flag flying in right field, with a backdrop of beige and red brick apartment buildings.

A noise pops, and a flashback recording from the 1990s plays over the loudspeaker:

"Now to honor America, especially the brave men and women serving our nation in the Persian Gulf and throughout the world, please join in the singing of our national anthem. ..."

The scene is award-winning singer Whitney Houston performing one of the most memorable renditions of "The Star-Spangled Banner" during the Super Bowl halftime show before 73,000 cheering fans.

The year was 1991. George H.W. Bush was president, the U.S. was engaged in Operation Desert Storm, and, at the end of the game, the New York Giants were crowned Super Bowl XXV Champions.

That same year, on a much smaller scale, a sporting event occurred at East 101st Street: A baseball program for New York inner-city youth, called Harlem RBI, was born.

Program executive director Richard Berlin described the property as "once a garbage repository for the Washington Houses," referring to a public housing development in existence since 1958, "an unused parking lot, and what we call a tree jail: a park that was asphalt and chain-link fence and a bunch of trees planted."

East Harlem, then and now

Historically, East Harlem, a predominantly minority neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, has endured a high poverty rate and low reading and math scores among public school students. They include a high percentage of special needs and ESOL (English for speakers of other language) learners.

For residents who moved out, East Harlem in 1991 was a very different place.

"It was very scary. Burnt-down buildings, a lot of homeless, drug addicts," said Marilyn Morales, the proud mother of Ian, a sixth-grader and champion pitcher for the Cooper Pilots.

Morales, who now lives in Westchester County, New York, commutes every day with her son so that he can play in Harlem RBI's summer league and become integrated in a neighborhood she is proud of today.

"We all have different attitudes, we all speak differently, we all dress differently," Morales said. "Being a part of New York City, that's what it's all about."

Morales says she wishes she could move back today, but it's not that simple. "It's too expensive, I can't live here!" she said, laughing.

25-year history

Thanks in part to an $85 million renovation, the East Harlem community is celebrating the 25-year anniversary of the program dedicated to helping inner-city students succeed and break the neighborhood's long-standing cycle of poverty.

Since 2005, Harlem RBI seniors have boasted a graduation rate of 96 percent, and a college-acceptance rate of 94 percent. In 2008, Harlem RBI added a charter-school program of its own, called DREAM.

With those figures, DREAM "outperforms the state, the city and the school district, while still serving a very high percentage of special-needs kids, English-language learners," Berlin said.

The executive director, who began with the program as a volunteer baseball coach in 1994, said the charter school fills "every one of our seats ... with a deserving child who wants to be here."

The lessons of baseball, he explained, serve as a practical metaphor for leading a successful life: "Baseball is a game of failure. If you fail seven out of 10 times, you are wildly successful in this game."

"I think for our kids, there is often an expectation — because of the way they look and where they come from — that failure is in their future, and that expectation comes from inside and outside their community," Berlin said. "So I think learning how to deal with failure and overcome it — which is … critical for any human being — may be especially important for our kids."

Confidence, perseverance, sportsmanship

To date, 2,000 boys and girls from East Harlem and the South Bronx, ranging from 5 to 22 years old, have become a part of Harlem RBI's success.

Ian says the best part of playing baseball is "getting educated and making new friends."

His mother said the program helps him stay focused in life.

"It keeps him off the street, it keeps him off drugs, hopefully, and it just helps keep him motivated," she said.

Some of the program's youth will go on to play baseball in high school, college or beyond. But the success of the program is built on the life skills that baseball teaches: confidence, perseverance and sportsmanship.

"In school, if I'm stuck on a math problem or the teacher calls me — when somebody wants to help me or they keep saying, ‘oh, you know the answer' and they try to motivate — it kind of relates to when we come back on the field," said eighth-grader Taina Figueroa.

The star shortstop and pitcher, who has been with Harlem RBI for six years, says baseball has taught her to work as a team and to compromise — skills that could serve her well should she one day become a district attorney, which is her life goal.

But the best thing about the sport, she says, is the cheering.

"When people are on your side and they are rooting for you, it gives me motivation to hit the ball harder or pitch harder or run faster," Taina said.

She says nothing beats having her "second family" — her teammates — beside her on the field.

Win or lose, they are there for her.