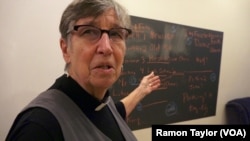

In her cozy first-floor office at Judson Memorial Church, the Reverend Donna Schaper spends hours strategizing, mobilizing, providing legal help and services for New York City’s undocumented immigrants. Often, she puts her intermediate Spanish skills to the test.

On any Tuesday or Thursday night, several hundred people show up at the church “trying to get help about a detained relative or a relative about to be deported,” said Schaper, Judson’s senior minister and co-founder of the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York City.

Sanctuary churches, like Judson, are fearful Donald Trump will act on his post-election pledge to deport 2 million to 3 million undocumented immigrants “that are criminal and have criminal records, gang members, drug dealers...”

President Barack Obama also targeted undocumented immigrants with criminal records and deported a record 2.5 million people in his two terms in office.

The PICO Network, a coalition of faith communities that provide sanctuary, says five people are currently being sheltered in coalition churches as they fight to stop Obama administration deportation orders.

The cases are in Denver, Philadelphia, Phoenix and Chicago.

Sanctuary, then and now

What is known as the “sanctuary movement” began in the 1980s when congregations across the United States began providing shelter to asylum-seekers fleeing civil war in Central America.

Today, millions of undocumented immigrants from all walks of life can seek sanctuary. In New York City alone, 1 in 3 residents was born outside the United States, and half a million are undocumented.

Immigrant-friendly organizations that played a role in protecting immigrants more than 36 years ago are again overburdened with requests.

Like 40 other cities and 364 counties nationwide, New York is a sanctuary city. Since 1989, it has limited assistance to federal authorities that might result in an undocumented immigrant’s deportation.

Proponents of tougher immigration laws, like Republican Senator Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania, object to the sanctuary cities.

“We confer this special privilege on, in many cases, dangerous, violent criminals because they came here illegally,” said Toomey, who has proposed legislation that would strip cities of federal development assistance if they fail to cooperate with federal authorities.

The impact of his bill, called the “Stop Dangerous Sanctuary Cities Act,” would fall mainly on low-income neighborhoods that rely on the federal aid for affordable housing and public services.

Watch: In New York, Fear of Deportation Propels Sanctuary Movement

IDNYC

“What makes a criminal?” asked Poonam Dass, whose family migrated from Suriname when she was 3 years old.

Dass, who lives in Queens, New York, is a beneficiary of President Barack Obama’s 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy, which protects undocumented immigrants whose parents brought them to the United States as children.

“Technically, I’m a criminal because I don’t have a piece of paper that determines my status,” she said.

In 2014, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio tried to mitigate the piece-of-paper problem by creating the nation’s largest municipal identification card program, called IDNYC, which requires proof of identity and residency, but does not ask for information regarding immigration status.

Almost 1 million people applied for and received the identity documents. But the program has come under fire in recent weeks over a provision that authorizes the city to destroy all personal data if it is pressed to turn over that information to the federal government.

“The reason people were willing to trust us is that we made it very clear we would never be in a situation where it would lead to their deportation, and we’re going to keep that pledge,” de Blasio said during a press conference in December.

But two Republican New York State Assembly members have filed a lawsuit to block any such purge of personal data.

Assemblyman Ron Castorina, Jr. told VOA the purpose of his action is to prevent any violation of the state’s Freedom of Information Laws (FOIL) and to guard against fraud.

“We’re asking for [the information] to be maintained for security issues,” Castorina said. “No one’s looking for a list to round people up.”

Sanctuary schools

The president-elect, who once spoke of deporting all undocumented immigrants, now speaks only of deporting those with criminal records. He has also indicated he may find a solution for DACA recipients.

“We’re going to work something out that’s going to make people happy and proud. But that’s a very tough situation,” Trump said in a Time Magazine “Person of the Year” interview in December. But this has not eased the fears of DACA beneficiaries like Dass.

Anand Ahuja, a lawyer and co-founder of Indian-Americans for Trump, says DACA beneficiaries should not expect to escape the consequences of their parents’ actions.

“It’s the fruit of a poisonous tree,” Ahuja told VOA. “If you can inherit your parents’ assets, you should inherit your parents’ liabilities also.”

Only by setting a strong precedent, he argues, can the government deter others from illegally entering the country.

Because of the fear many students face, a number of New York City-based universities have joined the mayor’s sanctuary efforts.

In the event DACA is either “terminated or substantially curtailed,” wrote Columbia University Provost John Coatsworth, “the university pledges to expand the financial aid and other support we make available to undocumented students.”

While deeply skeptical of Trump’s intentions, immigration lawyer Victoria Campos doubts the president-elect will ultimately repeal DACA, a program she described as “very strict” with regard to criminal records.

“You’re not talking about immigrants that are just being protected, these are people with credits, these are people with debts,” said Campos, who reported a post-election surge in cases involving minors. “Not to mention the manpower that it would take.”

Safety concerns

One of the fundamental debates surrounding sanctuary cities — apart from their legality — is whether they put residents at danger or make them safer.

“I have met with many of the great parents who lost their children to sanctuary cities and open borders,” Trump said during an immigration speech in August.

But Francis Madi, a regional outreach associate with the New York Immigration Coalition (NYIC), said the public is at greater risk if undocumented residents are afraid to report crimes.

“If people don’t feel comfortable enough to come to the police, then there’s not going to be any type of trust and the police is not going to prevent these crimes from happening in the future,” Madi said.

Guiding the spirit

Moving gently back and forth on her rocking chair, Reverend Schaper lets her eyes wander as she ponders the future of some of her closest friends.

“If [Trump] follows through with what he says he’s going to do, it will radicalize the immigration movement, and that will be a good thing.” She pauses. “But the suffering — the human suffering — along the way will be horrifying.”

At 70, Schaper says she is both emboldened and tired. Suddenly, her face lights up.

“The first week we had our friend in physical sanctuary here, a hundred or so undocumented people showed up and threw a great party, and brought food they probably couldn’t afford and drink they probably couldn’t afford, and it was so beautiful.” She smiled. “I believe people will take care of each other.”