As Hurricane Katrina washed over New Orleans in August, 2005, live TV news reports showed dramatic images of levees breaking, and water inundating a wide swath of neighborhoods. Tens of thousands of people stayed in the city because they had no means of getting out or they didn't believe the storm would be as bad as it was. Water rose to the treetops. Houses were underwater. Residents were evacuated to the city's poorly-equipped convention center, where sanitation conditions quickly deteriorated.

Seeing these televised reports at his home in New York City, comic book artist Josh Neufeld was deeply disturbed. He recalled the helplessness he had felt after the September 11th attacks. "There was nothing to do. There was no way to give blood. There were no survivors," he says. But four years later, he explains, "actually this time, being able to do something was a very powerful motivating factor for me."

An artist's perspective

Neufeld went to the local Red Cross office to volunteer. The private aid organization sent him to Biloxi, Mississippi, a city just east of New Orleans that was also hard-hit by Katrina. He spent three weeks working on an emergency response vehicle. His job was to help feed people whose homes had been destroyed. He worked 16 hours a day and slept in barracks with 600 other volunteers.

It was a different experience from the daily life of an artist. Neufeld blogged about it. That blog turned into a self-published magazine of his blog posts along with photographs from Mississippi and New Orleans.

The journal caught the eye of publishers of the on-line magazine, Smith. They asked Neufeld to connect with Hurricane Katrina survivors and detail their experiences in graphic form.

"My biggest challenge," he says, "was to try to weave all of their stories together in a way that made it satisfying as a work of art rather than just a staccato listing of experiences." The result was a comic-book style graphic narrative, released in 13 installments on the Smith website. Those "chapters" eventually became a nearly 200-page graphic book, titled A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge.

One natural disaster, six up-rooted lives

Frame by frame, Neufeld shows what happened to half a dozen New Orleans residents.

Denise, a social worker, stayed in the city with her family and ended up at the convention center. Her account casts a new light on reports of looting by gang members. Neufeld says she told him they were helping those stranded in the city, taking care of the old people and people who were sick. "When evacuation buses were supposed to come, they made sure the young people and the old people and the sick people would be brought to the front of the line and not get crushed, and that they'd have priority." Denise also told Neufeld the looting that made national headlines was to bring back needed supplies. "They weren't just ripping off televisions and jeans and CDs. They were bringing back food and water and medicine and clothing and things that people really needed."

The storm sends people in new directions

While Denise was at the Convention Center, long-time resident Brobson was still at home, where he had invited friends over for a party the night of the storm.

Kwame, a pastor's son, headed to Florida and the safety of his brother's college dormitory.

Shop owner Abbass stayed to guard his store with his friend, Darnell.

Leo, a musician and comic book collector, heeded storm warnings and evacuated with his girlfriend, Michelle.

Disturbing colors for stressful times

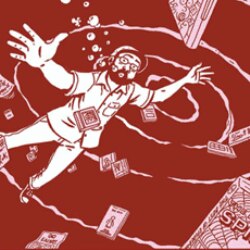

Neufeld's graphic style shuns the garish colors of mainstream comics. In A.D., he keeps to a single color pallet: black and white line drawings washed in one or two hues that change according to the action and the mood. Images in the chapter where the storm hits the city are tinted light green. The scenes of flooding are awash in bright pink. Kwame's family evacuates in a wave of yellowish-green. In a two-page spread, Neufeld depicts a nightmare that comic book collector Leo had about the flooding. He is sinking into putrid pink water as his ruined comics swirl around him.

The artist admits they're not pleasant colors. They're meant to convey the horror and tension of the situation. And, he says, that's an important distinction between his work and stories of comic book superheroes. "Generally mainstream comics tend to be very brightly colored and sort of hit you in the face with their intensity and over the top drama. And the type of work that I do, I want to connect with real people and real experiences," he says.

Neufeld adds that, "my particular approach to that is that I keep things at a sort of low-key tone. I don't do a lot of heavy shadowing and very extreme camera angles and dramatic super close-ups of someone screaming." Part of his mission as a cartoonist, he explains, is to prove to people that the medium of comics is suitable for any type of story and is an acceptable and worthwhile way to tell stories of any tone or subject.

A story that needs to be told

In the end, most of the characters in A.D. return to New Orleans to rebuild – both the city and their lives.

"It's a story that needs to continue to be told," Neufeld says. "And people need to know that New Orleans is still in recovery. It needs to be supported and appreciated as a unique place," Neufeld says.

He believes his new graphic narrative not only documents this story, but provides a valuable and accessible resource for those hoping to learn about Hurricane Katrina and its impact on one of America's best-loved cities.