“Call someone Arab inside the city and then you can go in,” the Iraqi Special Forces soldier told my Kurdish colleague as we pulled into the main entrance of Kirkuk city.

“Really? But we are journalists!” my colleague replied, hoping to skirt the rule by sounding shocked.

“Just joking,” the soldier said, laughing. “You can go in.”

At that, we really were shocked. On Monday evening we were reporting on what looked like the beginning of a civil war between Arabs and Kurds, with mortars reaching kilometers beyond the city and armed civilians flocking to the fight. Kurdish Peshmerga forces were struggling to fend off Iraqi forces sent by the central government in Baghdad to take Kirkuk, an oil-rich city the Peshmerga have held for the past three years.

Thousands of people fled their homes Monday, amid reports of heavy casualties, at least from the Kurdish side of the conflict. But the following morning, the city was open and Arab soldiers were joking with Kurdish journalists.

The city was also quiet, with no signs of conflict except the flames coming from a Kurdish ruling party building as it burned to the ground. The Kurdish flag had been removed from the main government headquarters, but no one had bothered to remove every Kurdish flag in town.

“The most important thing for us is that Kurdish families come back,” said Ali Mehdi, a Kirkuk city council member and a member of the Iraq Turkmen Front, a political party representing Turkmen, one of several minority groups in the city.

Kurdish Families in Kirkuk

Among civilians in the city, the response to the rapid takeover varied by neighborhood, and ethnicity, with Arabs and Turkmen generally pleased with the shift in local power and Kurdish families mixed in their levels of distress.

In one Kurdish neighborhood, families were coming back after most people fled the day before.

Minutes after arriving back into her house, Nasreen, 35, burst into tears. The night before she had slept in a field with her thee children, her husband and a crowd of other scared families. The return trip was uneventful, but the symbolic loss of Kirkuk broke her heart, she said.

“I wish I had died before seeing this,” she added.

Across the street, outside a home topped with a large white pigeon house, another man, carrying a pistol, showed us bullet wounds on his chest from fighting Islamic State militants. He was also Kurdish, but disagreed with Nasreen.

“Of course I dream of an independent Kurdistan,” he explained. “But it wasn't the right time.”

The Iraqi-Kurdish standoff around Kirkuk began last week, when Baghdad announced that it would take back Kirkuk, by force if it had to, in response to a controversial independence referendum that won overwhelming support among Iraqi Kurds, but condemnation from Baghdad and the international community.

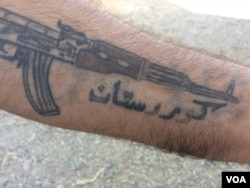

The man showed us his tattoo of a gun and the word “Kurdistan” and gave us a little insight as to why outside observers reported battles amid other reports that the Peshmerga forces had quickly retreated. The forces were divided by political party, he said. Some were ordered to stay and fight, others were told to stand down.

Down the street, Wushiar Khalid, a 22-year-old day worker, was riding an old bike with pink trimmings saying “Love and Peace.” He offered further explanation.

“The regular Peshmerga soldiers were not here,” he said. “But civilian volunteers took up arms against the gangs.”

By “gangs” he meant the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) that were recently formalized under Baghdad’s control, also known simply as Shia militias. While Khalid was deeply disappointed that Kurdistan lost control of Kirkuk, he said it was too soon to know if their fear that the PMUs would harm civilians was even realistic.

“It's only been one day,” he said.

Somber journey

On the way out of town, we see some families celebrating the change of guard, waving Iraqi flags. But most people went about their business without fanfair. Onlookers filmed the burning party building with their mobile phones as the fire department arrived to put out the blaze.

At a checkpoint just outside the city, Iraqi Special Forces seemed jubilatory, flashing the victory sign and posing for pictures. “We have been fighting IS for three years,” one soldier told us. “So we took this city easily.”

But beyond the massive berms Peshmerga soldiers have built to establish new defense lines between Kirkuk and Irbil, their regional capital, humvees lined the streets and units of Peshmerga soldiers guarded the highway.

“How was Kirkuk?” asked one soldier as he examined our IDs at a checkpoint. He looked like he had just swallowed rotten food.

“There were PMUs everywhere and a party building was burning, but otherwise it was really normal,” my colleague told him.

“Really?” he said. “This is so sad.”