As Tibetans prepared to celebrate a Buddhist new year festival with prayers and dance, police officers went to schools, airports and public squares to read out “21 kinds of dark and evil forces,” a list of new criminal targets.

“Number Two: Individuals associated with the Dalai Lama clique” — supporters of the Tibetan spiritual leader — said the list issued by the Chinese region's public security bureau. Slightly further down the list were people described as “Protecting the Mother Tongue” — those seeking to preserve the Tibetan language.

These targets are part of a new national campaign against alleged organized crime in China that expands the range of people law enforcement officials can take into custody in the name of preserving peace and order.

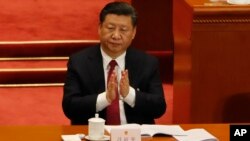

Analysts say the crackdown will help President Xi Jinping win political support in village, county and other lower-level jurisdictions. That could boost his legitimacy as he prepares to rule the country indefinitely following a surprise move to abolish presidential term limits.

More than 10,000 people have been seized within a month of the crackdown's launch in late January. Its wide scope has raised concerns that it will be used to ensnare political opponents of the ruling Communist Party and that police will have wide leeway to apprehend anyone they consider a troublemaker.

The official Xinhua News Agency reported that while previous campaigns against organized crime have focused on “social security,” the latest drive aims to “strengthen political power at the grassroots level.” In some local jurisdictions, particularly in rural areas, governments and industries are controlled by gangs.

The high-profile initiative encourages local authorities to go after “soft forces” — a reference to nonviolent behavior that the government nevertheless views as a threat to “political security.”

Legal experts and rights groups said the anti-mafia drive’s political focus is troubling.

“Police are given too much power to handle cases at their own discretion, which is in violation of human rights” said He Weifang, a lawyer who has advocated judicial reforms.

“People worry that the crackdown on ordinary crimes will turn into ideological and political repression,” he said. He noted that nonprofit groups with connections to the West, rights lawyers and some critical online commentators have been accused of threatening political stability.

In addition to Tibetan activists, announcements of the anti-organized crime drive have targeted Xinjiang “separatists,” people with complaints about medical malpractice, and organizers of people who petition government agencies over grievances.

In Tibet, residents have protested what they regard as China's heavy-handed rule and worry that their culture is being destroyed through the steady erosion of their native tongue. Beijing, meanwhile, accuses the Dalai Lama of trying to split the territory from China.

Authorities said “zero tolerance” will be shown in the restive far western region of Xinjiang, where notices about the campaign said it would be combined with “anti-separatist” efforts. Ethnic Uighur Muslims native to the region have experienced increasing religious and other restrictions in recent years.

“It is a worrying sign that China's top court announced that those who ‘threaten political security’ would be targeted alongside drug kingpins, loan sharks and other types of criminals,” said Maya Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch.

The campaign could “easily double as a partisan purge,” Wang said in a statement.

The potential for abuses from a crackdown of this nature was laid out in 2009. Bo Xilai, then party chief of the southwestern city of Chongqing, led a crackdown on alleged gangs that was later shown to have also been used to target his political rivals. People who had been arrested and jailed later described being tortured and having their assets stolen by the authorities.

In the new campaign, some police stations have posted quotas for how many criminals they sought to apprehend, and local publications have touted recent arrests.

“In one week, 1,481 people were captured,” said a headline in a business newspaper in central Henan province. It said more than 10,000 officers were participating in the sweep.

One Henan police bureau said it would give 30,000 yuan ($4,740) to anyone who reports crimes by mafia-like organizations that end up being prosecuted.

A police station in central Hubei province displayed its anti-gang efforts on the Twitter-like Weibo platform with images of officers inspecting businesses and questioning people in a dark room.

Police are spreading the message by holding public gatherings and meetings, handing out brochures and festooning buildings with banners.

The attention to so-called organized crime adds another notch to Xi's anti-corruption drive, which has taken down more than a million low and high-level officials since it was launched six years ago.

Political commentator Hu Xingdou said while the anti-graft campaign strengthened Xi’s grip on power at the top, the gang crackdown is aimed at “winning support from people at the grassroots level.”

An opinion piece on the website of state broadcaster CCTV warned that while “high enthusiasm” for the crackdown is a positive thing, local authorities should not be “swept away” by quotas.

Wang Guoqing, spokesman for China’s political advisory body, assured reporters that the anti-organized crime campaign would not become a competition between local governments seeking to improve their political records.

“Every case should be ironclad and able to stand the tests of history and the law,” he said.