Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has a deep bond with the United States and Americans.

And as he prepares to give a controversial speech to the U.S. Congress in Washington on Tuesday, he knows the halls of political power in America as well many home-bred U.S. politicos.

The man nicknamed “Bibi” was born in Tel Aviv in 1949. But seven years later, his father brought the family to the suburbs of Philadelphia.

Professor Ben-zion Netanyahu, a Jewish historian and staunch Zionist, was no stranger to the U.S.

During the 1940s, the elder Netanyahu had spent eight years in the U.S. as the executive director of the New Zionist Organization, lobbying for the creation of an Israeli state and the rescue of Europe’s Jews.

Ben-Zion is credited for having convinced the Republican Party to adopt into the GOP platform a call for “refuge for millions of distressed Jewish men, women, and children driven from their homes by tyranny” and establishment of a "free and democratic" Jewish state. The Democrats followed suit a month later.

The Israeli state that the elder Netanyahu envisioned did not include dividing then-Palestine, but creating a single Israel that would include present-day Jordan. Ben-Zion’s views were uncompromising.

“The Bible finds no worse image than this of the man from the desert,” Time magazine quoted him in a 2009 interview. “And why? Because he has no respect for any law. Because in the desert he can do as he pleases … His existence is one of perpetual war.”

'Organized and committed'

Observers say the younger Netanyahu was raised on “a fear of the enemy.” It was almost inevitable, they say, that the son would cling to his father’s ideology.

“To a considerable degree, Bibi Netanyahu’s internal struggle as Prime Minister is a struggle between an inherited ideology and the tug of political contingencies,” columnist David Remick wrote in the New Yorker in May, 1998. “His dilemma is always to what degree he can, or should, remain true to the ideals, the stubbornness, of his father.”

Just as his father had, the younger Netanyahu seemed to split his time between the U.S. and Israel.

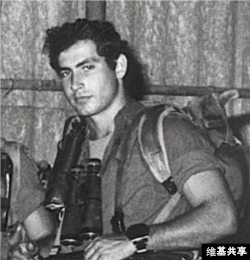

In 1967, he returned home to join the Sayeret Matkal—the Israeli Defense Force's elite Special Forces unit.

In 1972, he was discharged from the IDF and returned to the U.S. to study architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

In October 1973, he returned to Israel for 40 days to fight in the Yom Kippur War.

He then returned to the U.S. and spent the next four years studying at MIT, where he earned two degrees--in architecture and management. Former professor Leon B. Groisser would later remember Netanyahu as bright, organized, strong and powerful.

“He knew what he wanted to do and how to get it done,” the professor told MIT News in June, 1996. “He's not the flippant, superficial person I keep reading about in the newspapers. He was organized and committed.”

In May 1976, he began work on his doctorate in political science, but left the U.S. abruptly after his brother Yonatan [Yoni] was killed in June 1976, during an Israeli rescue operation to free passengers of an Air France airliner being held in Uganda.

Upon another return to the U.S., he was recruited as a management consultant for the Boston Consulting Group in Massachusetts, working at the company between 1976 and 1978.

He developed a good friendship with one of his colleagues there, future U.S. presidential candidate, Mitt Romney. Romney later said Netanyahu had a “strong personality with a distinct point of view.”

It was during the 1970s that Netanyahu, now in his 20’s, changed his name to Benjamin Ben Nitay, after a Talmudic sage by the same name.

Netanyahu said he changed his name so that it could be more easily pronounced by Americans, but critics in Israel later said that he was more “American” than Israeli.

He was only 28 when he appeared in a debate on Boston public television about the Middle East (above). Introduced as a “graduate of MIT, an Israeli, and a man who has written widely about the Palestinian issue,” Netanyahu said he thought the U.S. should oppose the creation of a Palestinian state:

“It is unjust to demand the creation of a 22nd Arab state and a second Palestinian state at the expense of the only Jewish state,” he said. “I believe we should fight for our survival. If I have to, I will fight again, but I hope not to.”

Devastated over the loss of his brother in Uganda, Netanyahu helped form the Jerusalem-based “Jonathan Institute of Peace” with a purpose, he later wrote, “to educate free societies as to the nature of terrorism and the methods needed to fight it.”

He organized two international conferences on terror in Jerusalem, which were attended by a number of leading U.S. political figures—George P. Schultz, former FBI Director William Webster and former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Jeane Kirkpatrick.

In those conferences, Netanyahu detailed how, he believed, the Soviets were training Muslim terrorists, and, it is said, strongly influenced the way the U.S. crafted its war on terror.

“The root cause of terrorism lies not in grievances but in a disposition toward unbridled violence. This can be traced to a world view which asserts that certain ideological and religious goals justify, indeed demand, the shedding of all moral inhibitions.” – Benjamin Netanyahu, in Terrorism: How the West Can Win, 1987.

When former Israeli ambassador to the U.S. Moshe Arens came to Washington, he appointed Netanyahu as his information minister. From this point on, the young diplomat’s rise was meteoric.

In 1984, Netanyahu was appointed Israel's ambassador to the United Nations.

Returning to Israel in 1988, he was elected to the Knesset on the Likud party list and was appointed Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs.

He became one of Israel’s most effective—and recognizable—spokesmen. During the first three days of the 1991 Gulf War, he gave 50 television and radio interviews to international media, such as this interview with American journalist Tom Brokaw:

“With Netanyahu, the American television viewer was provided with someone who looks and sounds ‘like us’ and who markets a tried-and-true product: Israel, the American ally, securing Washington's interests in the Middle East against radical Soviet-Arab-Muslim terrorist bogeymen,” commented political analyst and journalist Leon T. Hadar that year.

Netanyahu has given many speeches in Washington. But two stand out in particular.

In January, 1998, during his first premiership, Netanyahu addressed hundreds of Christian and Jewish supporters at a Washington D.C. hotel. He also met with Christian evangelical leader Jerry Falwell, a vowed Bill Clinton-hater who had accused the U.S. president of drug peddling and even murder.

“By stressing his alliance with some of the administration's fiercest critics, Netanyahu steered the pro-Israel effort -- traditionally and obsessively bipartisan -- in the direction of the partisan wars,” read one commentary at the time.

In a speech to the U.S. Congress in 2011, Netanyahu got 20 standing ovations for his comments.

“Israel will not return to the indefensible boundaries of 1967,” he said. It was clear, the Christian Science Monitor noted, that Congress stood with Israel, not with U.S. President Barack Obama.

On Tuesday, Netanyahu will address Congress once again, this time to try to block a nuclear deal with Iran. News reports say more than 30 Democrats plan to boycott the event.

One poll shows that almost half of all American voters say that Congress should not have invited Netanyahu to speak without first notifying the President Obama.

“It’s important for us to maintain these protocols, because the U.S.-Israeli relationship is not about a particular party,” Obama said, explaining why he would not be meeting with Netanyahu this time around. “The way to preserve that is to make sure that it doesn’t get clouded with what could be perceived as partisan politics.”

But in a Monday morning speech in Washington to the American Israeli Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), Netanyahu expressed "boundless gratitude" to both parties in the U.S. Congress for their long-term support of the Jewish state.