Sirens wail frequently outside Bronwyn Mayden’s office, with ambulances and squad cars rushing to the University of Maryland Medical Center half a block away. It’s a trauma hospital, the one where 25-year-old Freddie Gray wound up dying in April from a neck injury sustained in police custody.

Mayden deals with trauma, too, but of a different kind. Assistant dean at the university’s School of Social Work, she’s also executive director of Promise Heights, an academic-community partnership that assists one of West Baltimore’s neediest neighborhoods just over a mile from her office.

Upton-Druid Heights – like the adjacent Sandtown neighborhood where Gray grew up, and like many other poor areas in the U.S. and abroad – cries out for urgent care.

"This is a neighborhood of extreme poverty," said Mayden, 62, who also grew up in predominantly black West Baltimore.

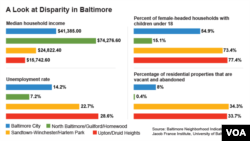

More than half of the neighborhood’s households have incomes below $15,000; three out of five youngsters live in poverty. It has the city’s lowest life expectancy, at 63 years, and among its highest rates of unemployment and incarceration. Sagging, boarded-up row houses mar many streets.

"I could take you in apartments that we’re attempting to raise children in," Mayden said, "that are filled with rats."

The challenges have grown since Gray’s death April 19 sparked sometimes-violent demonstrations against excessive use of force by police.

The beleaguered city now grapples with a soaring homicide rate, the worst in 40 years. May alone brought 43 homicides.

Several West Baltimore residents told The Associated Press they suspect sudden neglect by law enforcement and see more brazen criminal behavior, such as guns flashed on the street. Arrest rates have sunk citywide.

Offsetting challenges

Promise Heights was designed as a counterweight to those burdens.

Launched in 2009, it uses four public schools – two elementary, a middle and a high school – as hubs for delivering services to nurture students, their families and the entire community.

The university and 25 other partners – city and state governments, philanthropies and churches – offer comprehensive, “cradle-to-college-to-career” support. That ranges from enrolling pregnant women in the city’s prenatal care program, to tutoring youngsters, to counseling parents on paying bills or even lining up a burial plot.

One of these community schools is Historic Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Elementary (HSCT).

Mayden placed social worker Henriette Taylor there to coordinate services for its 467 pre-K through fifth-graders and their families. The school sits across the street from McCulloh Homes, a public housing project that served as a backdrop for the gritty HBO series “The Wire.”

The drama continues in real life, said Taylor, who introduced herself after school one spring day as she shepherded some youngsters heading home to McCulloh. As she said later: "I work in an at-risk, trauma-informed school. My kids experience all types of violence."

Over the Memorial Day weekend, for example, a 9-year-old student lost an older friend to gunfire, Taylor recounted. "Violent death is not a stranger in our neighborhood – except now people are watching."

Mental health professionals continuously staff a resource room where teachers can bring students showing signs of anxiety or anger. It has crayons, Play-Doh and stress balls for those too young or too frustrated to articulate their concerns.

"When we talk to the children, they say, 'Everything’s great, everything’s fine,'" Taylor said.

But their artwork says otherwise.

After this spring's rioting brought in the National Guard and legions of additional law enforcement, one youngster drew "little brown figures, all smiling, then little blue figures with scary teeth," Taylor said. "... We see a lot of pictures about tanks, and inside the tanks [are] people with guns."

Chronic stress and its impact

The sound of gunfire in the night sends fifth-grader Shamira Wedlock bolting to her step-grandmother’s bedroom for reassurance, she said in a phone conversation days after meeting a reporter near her school.

Her older sister, Kishawna Pinder, was fatally shot in a triple homicide in West Baltimore on March 19, 2013, a date Shamira has committed to memory. Now she monitors what's happening around her.

"I watch the news every day, and sometimes I hear stuff and I Google it on my grandma’s phone," the 11-year-old said.

Steady exposure to community violence, and poverty itself, carries risks for youngsters – whether in a poor U.S. neighborhood, a refugee camp in Syria or a bunker in eastern Ukraine.

It "impacts the stress system of young children – and that has a lasting effect on their biology and on their brain development," said Nathan Fox, a developmental psychologist and neuroscientist who runs the University of Maryland Child Development Lab in College Park. Stress prompts the body to release cortisol, a hormone that, in elevated amounts, "actually has a neurotoxic effect on brain connections."

Chronic stress can stunt brain development, trigger fear and anxiety and compromise learning. So Promise Heights strives to ensure a supportive climate at school and at home.

"We work with those social-emotional factors ... so their little brains are ready to receive the instruction that their educators are giving them" at HSCT, Taylor said.

Involving the young

Outreach to families starts before youngsters reach pre-K, sometimes even before they’re born, and continues through early adulthood. Promise Heights personnel, including interns from the School of Social Work, visit neighborhood homes to let residents know about available resources.

"We knock on doors and we find every pregnant woman that we can … to get her into care," Mayden said.

The women are referred to B’more for Healthy Babies, a city health department program aimed at reducing mortality rates. In Baltimore, black babies die at three times the rate of white babies.

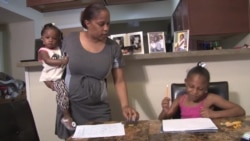

Promise Height’s Parent University teaches grownups how to better care for their offspring to improve bonding and learning.

One morning a week for 10 weeks, they come for a breakfast and training in areas such as good nutrition, immunization, or reading as a means of bonding and building vocabulary. They also learn how to set boundaries and use discipline other than spanking.

"We teach them how to sit on the floor and look into their kids' faces," said JoAnn Brewer Wedlock, who leads a Parent U peer group and is Shamira Wedlock’s step-grandmother. "... We see a parent not interacting, we step in and say, 'Turn your child around, let him face you.' We teach them to read to the children."

Most of the 86 participants so far have been single, unemployed moms with a basic education. Almost a third improved how they responded to their children’s needs – soothing them, playing with them and encouraging cognitive development, program administrators said.

Depends on partnership

Promise Heights has a host of other programs and partners, too.

The nearby Union Baptist Church’s congregants tutor youngsters in reading, for instance, and the nonprofit organizations Laureate Education and KaBOOM built the school a playground last year with help from the Baltimore City Police Academy and hundreds of other community volunteers. The local Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation renovated the school’s library for students and their families.

With United Way of Central Maryland, Promise Heights runs a family stability program intended to reduce household moves that can disrupt youngsters’ academics as well as relationships at school and in the neighborhood. More than a third – 38 percent – of HSCT students moved during the previous school year, down from a high of 58 percent in 2009.

The program has some funds "to stave off eviction or to pay for rent," Mayden explained.

In one recent case, she said, a woman facing eviction appealed for help from the program. A case manager "got a meeting going, the landlord came, he listened. He said, ‘How would you like to own this house?'" Mayden recalled. They structured a deal enabling the woman to rent to own within 30 years.

As a partner, the University of Maryland Baltimore assists not only with social work but through several of its other professional schools. Law students host periodic sessions to help neighborhood residents with housing problems and small claims. Dental students swing by the four Promise Heights schools to check youngsters’ teeth and encourage good brushing and flossing habits.

The university hospital’s Breathmobile – a recreational vehicle outfitted with exam rooms – routinely visits the two elementary schools and a Head Start program to treat more than 90 young patients with asthma. The condition can be exacerbated by pesticides used in public housing projects, Mayden said, and is a leading cause of absenteeism.

Mayden cites other gains that she attributes, at least in part, to supportive services, including an expanded learning day and after-school enrichment programs for language, music and arts.

The Promise Heights schools "are calmer – they’re not suspending as many kids," she said. "I believe children feel safer."

Accolades for schools

Mayden has some cause for optimism.

On Tuesday, a national program announced Promise Heights and several local partners will get at least $75,000 to develop a comprehensive youth violence prevention plan for Upton-Druid Heights. Theirs is among 18 community collaborations out of 300 applicants nationwide selected for BUILD Health Challenge grants.

And on Wednesday, the national Coalition for Community Schools honored Baltimore Community Schools – a network of 45 public schools, including the four in Promise Heights, all overseen by the Family League of Baltimore – for reducing chronic absenteeism and bolstering participation in after-school programs.

The coalition also lauded five individual schools nationwide, including three in Baltimore, for excellence and provided each with a $2,500 award at a ceremony in Washington. HSCT was among them.

"We chose Taylor and her school because they showed really strong family engagement practices that have clearly helped raise the performance" of students, said Mary Kingston Roche, public policy manager for the coalition, which supports approximately 100 community school networks in 38 states.

A measurable difference?

It’s still not clear how much Promise Heights – or any other program of wraparound services – ultimately will help poor youngsters overcome chronic disadvantages and narrow the yawning socio-economic gap in student achievement.

See related video by VOA's Jeff Swicord:

In 2012, Promise Heights got a $500,000 planning grant through the federal Promise Neighborhood program to support distressed neighborhoods. It was one of 50 communities to get some funding; 12 of them, considered full-fledged Promise Neighborhoods, got additional money.

"Right now, there’s not a lot of evidence" compiled in that program, though that will change over time as data accrue, said Megan Gallagher, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute, a Washington think tank. She’s evaluating a site in Washington, D.C.

"It takes years of all these partners working together to drive these outcomes," she said.

Meeting needs

Ultimately, improvement comes down to commitment and resources, the Promise Heights people say.

Days after the April rioting, Mayden said she saw this as a pivotal moment in Baltimore, one where the city leaders and residents "will look at neighborhoods like this, economic policies, what can we do differently…. Now we have some opportunity to begin to move forward."

She and others had hoped the media spotlight would yield sustained attention and stronger support for schools in distressed neighborhoods. But in May, Maryland’s governor announced the state was cutting its education budget, trimming $11 million from Baltimore city schools.

"My principal and other administrators do battle just to get basic resources," Taylor said.

Air conditioners don’t work, and water fountains have been turned off because of lead from corroding pipes.

Worse, she said: "We have 24 computers for 467 students. We’re supposed to do all of our testing on computers. Our principal is supposed to make up a plan so that every student is familiar with computers before testing.… It’s not fair."

A more immediate concern is making provisions for summer school to minimize the notorious "summer slide" in academic skills. The school will host a program for roughly 50 students, fewer than it had hoped for.

"What are our children supposed to do during summer? All those political promises? Haven’t heard a peep," Taylor said recently. "I need people to protest when we get budget cuts.… There’s so much dire need."

Back at the university, Mayden reflected on those needs. The campus is just blocks from the Inner Harbor, a downtown waterfront development with tourist attractions such as an aquarium and major league baseball park.

"We’ve spent a lot of time developing the Inner Harbor," Mayden said. "Now we need to talk about the other Baltimore."