Native American tribal leaders, conservationists, wildlife managers and buffalo producers are exploring the cultural and economic benefits of restoring buffalo — known scientifically as bison — to tribal lands and beyond. They are addressing the issue at the first annual Tribal Buffalo Conservation Summit, a three-day event in Denver, Colorado culminating on November 3, National Bison Day.

Prior to the arrival of European settlers, tens of millions of bison grazed and stampeded across America's Great Plains in herds that could stretch 160 kilometers (100 miles) end-to-end. The huge animals were crucial to the lives and economies of Plains tribes, providing shelter, food, clothing, weapons, tools and even children's playthings. Tribes revered the animal as a gift from the Creator, and it was--and remains--central to their spiritual beliefs.

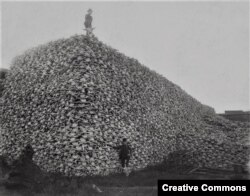

During the latter half of the 19th Century, as part of its strategy to subjugate tribes, the U.S. Army slaughtered buffalo by the millions, and by 1900, fewer than 100 animals remained. About two dozen buffalo found a haven in Yellowstone National Park, where they have been protected and roamed freely ever since.

"The history of Native American people and buffalo is very similar in that we both now live on remnants of our former vast territories—buffalo in parks and refuges and Native Americans on reservations," said Jason Baldes, bison consultant for the Eastern Shoshone Tribe of the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming and tribal buffalo coordinator for the National Wildlife Federation's tribal partnerships program.

"After the atrocities suffered by Native American people through federal policy, we finally have the ability to finally return buffalo back to our communities," Baldes said. "It's really a way to help us heal."

Today, about a half million buffalo live in the U.S. and Canada. Most are not genetically pure, having been cross-bred with cattle, so they are classified as livestock, not wildlife. However, a genetically pure herd of about 5,000 bison roams freely throughout Yellowstone National Park.

More than 60 tribes comprise the Inter-Tribal Buffalo Council and today manage a collective herd of more than 20,000 buffalo—among them:

The Eastern Shoshone Tribe has partnered with the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) to restore 20 buffalo to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming with the goal of expanding the herd to more than 1,000.

The Blackfeet Nation in northern Montana launched a buffalo restoration program in 2016, releasing 88 buffalo from a historic herd from Elk Island National Park in Alberta, Canada.

The A'aninin and Nakoda tribes reintroduced 31 buffalo to the Fort Peck Reservation in north-central Montana in 1977. The herd now numbers more than 600 head, and with the help of the national non-profit conservation organization Defenders of Wildlife (DOW), the tribes have reintroduced genetically pure wild buffalo from Yellowstone.

The Assiniboine and Sioux tribes in 2000 purchased 100 buffalo from the Fort Belknap tribes and with help from the NWF and DOW, secured an additional 200 genetically pure Yellowstone buffalo in 2012; their arrival was documented in the video below.

These projects are a beginning, said Baldes, and tribes are a long way from restoring the herds of the past.

"The challenges are overcoming the assimilationist and colonialist mindset that restoring the buffalo is contrary to progress," he said. "At Wind River, we are working on a process to manage buffalo as wildlife, and that's extremely difficult because for some reason we're stuck in a paradigm of belief that we have to manage buffalo like cattle—having them fenced in and doing roundups, ear tagging and vaccinations."

Not 1860 anymore'

Baldes envisions expanding buffalo habitat from tribal to public lands, a prospect that makes western cattle and sheep ranchers shudder.

"We certainly understand past cultural connections to bison grazing and the fact that there is an industry burgeoning around bison now," said Ethan Lane, executive director of federal lands at the National Cattlemen's Beef Association. "But the reality is that a 1,000- or 2,000-pound (450- or 900-kilograms) grazing animal needs to be managed in that environment, and the idea that you are just going to roam free without any management is just not realistic.

He cites fears about the transmission of brucellosis, an infectious bacterial disease that can decimate sheep and cattle herds. Ranchers also worry that wild-roaming buffalo could exhaust grazing and water resources.

"Our antennae really go up when we see these pushes to pursue an idealistic, fence-free roaming bison herd. It's simply not 1860 anymore, and you can't go into these things with blinders on."

At this week's summit, tribes and leaders from the NWF, DOW and the World Wildlife Fund will discuss the spiritual and cultural benefits of restoring buffalo, share management success stories, and address ranchers' environmental concerns.

"The story of buffalo is not unique to Native Americans," said Baldes. "The buffalo has been designated America's national animal and is important to all Americans. We have to begin thinking about making room and allowing buffalo to be buffalo."