In celebration of the National Park Service’s 100th anniversary this year, adventurer Mikah Meyer is traveling across America with the goal of visiting every one of the more than 400 sites within its jurisdiction.

The young traveler set out from Washington, D.C., in June and has already experienced dozens of sites. And VOA has been following him every step of the way.

He recently wrapped up visits to three national parks… a historic battlefield, a peace memorial and a U.S. presidential home with a famous front porch. All three sites, connected by history, gave Mikah a rare window into America during the 1800s.

The War of 1812 – a short history

In a military conflict that is often referred to as America’s second war of independence against the British, there were no declared winners. But despite humiliating losses for the U.S., especially when the British captured and set fire to much of Washington, including the U.S. Capitol building and the White House, the Americans at the time believed they won the war… and with good reason.

They had successfully defended their sovereignty against British aggression, British capture of American seamen and British incitement and support of Native American attacks on U.S. citizens along the Northwest frontier. The Royal British navy was shocked by a number defeats at sea in ship-to-ship battles with American frigates.

And the British suffered humiliating losses in the battle of New Orleans, where its army experienced one of its worst defeats in history – at the hands of mostly untrained American volunteers which included blacks and Native Americans.

The war also secured American's westward expansion - something Britain and Spain were desperately trying to stop.

Ultimately Britain, the world's foremost military superpower, was forced to settle for a negotiated peace without any territorial concessions. The two sides eventually wound down the war with the signing of a peace treaty in Ghent, Belgium, on December 24, 1814.

Native American defeat

The biggest losers of the war of 1812 were Native Americans, who had aligned themselves with the British to defend their territories.

During the two-year and eight-month-long conflict, they lost their revered Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, who had formed a confederation of tribes to block American expansion into their territories.

They also lost sovereignty of their lands in the “Old Northwest” - territory that included the modern states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and the northeastern part of Minnesota.

The River Raisin National Battlefield Park in Monroe, Michigan, commemorates a series of battles that took place there in the winter of 2013 when it was known as Frenchtown, Michigan.

From January 18–23, the north bank of the River Raisin became a battleground where the Americans and the British fought for control of Michigan and the Lower Great Lakes, and - some say - for the future of Frenchtown, Canada, and Tecumseh's alliance of Native American tribes. The battles ended with a decisive victory for the British and the indigenous tribes. It took about nine months for U.S. forces to regain their momentum.

Encompassing about 30 hectares (76 acres), River Raisin is one of four national battlefield parks within the national park system, and the only one that focuses on the War of 1812.

Atrocities committed on all sides

Mikah said his main takeaway from his experience there was how openly and fairly the National Park Service has handled a battle site where “all sides committed atrocities, including the United States.”

“Usually we talk about ourselves only as the good guys and everything we did was as heroes,” he said. “But they really acknowledge that every side did some really nasty things to each other and they want to make sure that they are telling all those sides of stories.”

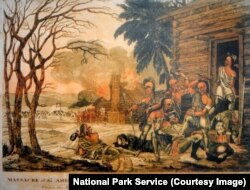

To make his point, he gave the example of a painting on display there that depicts Native Americans scalping Americans, which he described as “propaganda by the U.S.”

“It was Native Americans scalping Americans but they were holding knives and whiskey that was labeled with labels from Britain, so the idea was to try to incite the rest of America into being angry at the British because the British had enlisted the natives to fight for them.”

Mikah got a tour from a park ranger, who told him he had to be careful about his description of the park's history, "depending on who is visiting - if it's a native person, if it's a Canadian or Brit, [Canada was part of the British colony then] or if it's somebody from the U.S. - because people can get really offended.”

“One man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter, so it depends on who's hearing the story,” the ranger added.

“Remember the Raisin!" became a popular rallying cry during the War of 1812 after the battles in River Raisin. The aftermath of the forced removal of Native Americans from the Northwest Territory at the conclusion of the war continues to influence the United States today.

Battle of Lake Erie

A major turning point in the war came on September 10, 1813, when U.S. Captain Oliver Hazard Perry led a fleet of nine American ships to a victorious battle over six British warships on Lake Erie off the coast of Ohio.

It is considered one of the biggest naval battles of the War of 1812.

By winning control of the lake, the Americans were able to cut off British forces, and their Native American allies, from their supply base. It also allowed the Americans to gain control of the Northwest Territory, recover the city of Detroit, which had fallen into British hands, and kill Tecumseh.

Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial in Put-in-Bay, Ohio, was established to honor those who fought in the Battle of Lake Erie, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Put-in-Bay.

Mikah pointed out that the focus of the historic site is not to commemorate the battle itself, but “to celebrate the long-lasting peace among Britain, Canada and the U.S. that still endures,” and also the world's longest undefended border, about 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles).

“The whole town - and all around the island - they have American flags and British flags, local flags and peace flags,” he said. “So I think as a community, they’ve really taken on this idea of representing this peace that has been lasting since the Treaty of Ghent.”

“Don’t give up the ship”

During his visit to the Peace Memorial, Mikah noticed the recurring phrase “Don’t give up the ship!” posted in various forms throughout the town of Put-in-Bay.

“That was their battle cry,” he explained. “Because the U.S. had nine ships and the British had six - the U.S. lost their flagship right away – the Lawrence - and then ended up transferring the flag over to the Niagara to finish the battle and basically it was this idea of don't lose this battle.”

A fitting symbol

The park’s centerpiece, a Doric column rising 107 meters (352 feet) over Lake Erie, stands about eight kilometers (five miles) from the U.S.-Canadian border.

The pillar “is the tallest open-air observation deck in the entire national park system,” Mikah noted, “even taller than the Statue of Liberty.”

It is a fitting tribute, Mikah observed, “that at the base of that peace memorial there are three American sailors and three British sailors buried together in the crypt.”

A two-hour drive along the lakeshore from Put-in-Bay is Mentor, Ohio, home of James Abram Garfield, the 20th President of the United States, who served from March 4, 1881, until his assassination later that year.

His home, at the James A. Garfield National Historic Site, stands on what remains of the President’s 65-hectare (160-acre) farm, which includes a Visitor Center in a restored carriage barn built in 1894, a windmill and other buildings.

The most interesting part of Mikah's visit was learning how hard the National Park Service worked to make the interior appear as it would have when the president actually lived there.

Mikah said there had been many changes made to it both during and after Garfield's life, and he thought the park service did a "fantastic" job of recreating the rooms to their original state.

“So from that perspective, it was the best-maintained and the best-preserved house site that I've been to this whole trip,” he said.

Presidential porch

What Mikah also found interesting was Garfield’s “Birth-of-the-front-porch” campaign. In 1880, he would greet thousands of well-wishers during his presidential campaign as they stopped by his front porch.

“That’s because the train let out in the backyard of his farm, so people would get off the train and they would walk to his front yard and they would set up camp, they’d put up tents and wait for the next day to hear him speak on his front porch.”

Mikah remarked how unlikely that scenario would be in today’s presidential campaigns!

Coming attractions

In the coming days, Mikah will be visiting Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site in Buffalo, New York and Niagara Falls, which is not part of the US National Park Service, but will make a fascinating story nonetheless.

To follow Mikah and learn more about the places he’s traveling to, he invites you to visit him on his website.