National parks traveler Mikah Meyer spent the month of January immersed in American history as he visited a number of historic forts along the southeastern U.S. coastline.

Reliving American history at war

One of his first stops was Fort Sumter, a federal fort in Charleston Harbor, just off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina.

The fort is famous for being the spot where the first shot of the Civil War was fired, and also where the first casualty of that war occurred.

After a decade of cultural and economic tension between the North and South, it was here, on April 12, 1861, that the southern army opened fire, marking it as the day the Civil War began. It is considered by many to be the bloodiest battle in U.S. history.

Standing inside the large, fortified walls of Fort Sumter National Monument, looking across the water to the port city of Charleston, Mikah imagined what it must have been like all those years ago.

“It was under siege at one point for 17 months,” he noted. “There were cannons that could fire from where I'm standing on the fort all the way to the old town. So imagine living there for 17 months and wondering if at any point that a cannon [shot] might come.”

Connecting with the past

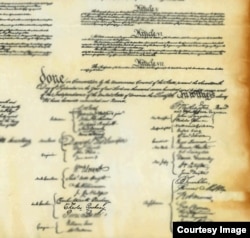

At the Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, also in South Carolina, Mikah had an opportunity to learn about a principal author and signer of the U.S. Constitution.

“Some people call him our forgotten founding father, but he was a political figure of early America who helped shape what our eventual Constitution ended up looking like,” Mikah explained.

The National Park Service helps preserve what remains of Pinckney's former plantation, and exhibits help tell the stories of 18th century plantation life for free and enslaved people.

Serendipity

During his journey through the south, Mikah, who’s on a mission to visit all of the more than 400 sites within the National Park Service, had an unexpected surprise...

“My phone started lighting up,” he said, with people letting him know that just south of Charleston, in the city of Beaufort, President Obama had just designated the Reconstruction Era National Monument as a National Park site. It was just two hours from where Mikah was traveling.

The Reconstruction Era (1861-1898) which followed the Civil War, was a transformative period in American history, as the United States grappled with the question of how to integrate millions of newly-freed African Americans into its social, political, economic and labor systems.

The new national monument will help tell that story.

“So all within the Charleston, South Carolina, area, you have these three sites now that are really related to either America becoming America, or America figuring out who America is,” Mikah noted.

Built like a castle

Driving south into the state of Georgia, Mikah stopped at Fort Pulaski National Monument. Built in 1847, the fort is considered one of the most technologically advanced fortifications of its time.

“This one was interesting solely just upon appearance,” Mikah said. “It had a moat, with water that circled the whole fort, which after seeing a number of forts that don't have moats, just that one little feature it's amazing how much more exciting that can make it!”

Just an hour south of Fort Pulaski, the scene couldn’t have been more different. At Fort Frederica on St. Simons Island, Mikah walked among the ruins of this once flourishing 18th century settlement.

“They're an interesting combination because Fort Pulaski, when it was built, it was one of the most technologically advanced forts of the time, and so perhaps because of that it’s still standing today… So it was an interesting one-two punch going from one extreme to the other,” he said.

Oyster heaven

Continuing on his journey south, Mikah stopped by the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve in Jacksonville, Florida, where he learned that an abundance of oysters in the area provided a steady supply of protein for the Native Americans who lived there.

“In fact there are so many oyster shells now that much of the land that is walkable in these swampy, marshy areas is actually just piled-up oyster shells that have turned into earth,” he explained.

That would explain why oyster shells were used as building materials for lodgings, which are still intact today.

“It's all of these little huts that were built out of a kind of paste of oyster shells and other minerals that when mixed together form sort of a brick-like substance,” Mikah said, adding that the Kingsley Plantation, where the lodgings are located, has the largest number of intact slave dwellings anywhere in North America.

Continuing down the Florida coast, Mikah squeezed in a quick visit to Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, a well-preserved site in the popular city of Saint Augustine on the ocean.

Followed by a brief visit a little farther south to the much smaller Fort Matanzas, “which was kind of a Castillo de San Marcos maybe on a one-eighth scale,” Mikah said. “It’s just a very small fort with one turret.”

The young traveler said visiting these historic sites - both large and small - made him appreciate the efforts of the National Park Service in preserving these national treasures for all to enjoy - and learn from.

Mikah invites you to follow him on his website, Facebook and Instagram.