Mexicali’s “Albergue del Desierto” — Shelter of the Desert — is the last place adolescent migrants may find refuge, a hot meal, and a communication life-line before attempting any trek into the United States, legal or otherwise.

It’s also the first place many land after they have been deported.

In the 29-year history of the Baja California, Mexico migrant shelter — created for border crossers to feel “safe, heard and respected” — director Mónica Oropeza Rodríguez has witnessed National Guard deployments take effect under each of the past three U.S. administrations, Democrat and Republican.

And yet, “people come again and again and again,” out of necessity, Oropeza Rodríguez told VOA.

WATCH: National Guard Effect: A Deterrence for Would-Be Crossers?

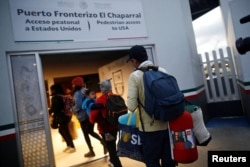

This time, nearly 1,000 National Guard troops have been deployed along the 3,000-kilometer U.S.-Mexico border — with more on the way — in response to what the Trump Administration has labeled a crisis of “lawlessness” created in part by a caravan of 1,500 migrants that had been heading across Mexico to the U.S. Border. A few hundred of the migrants arrived at the border in Tijuana earlier this week.

“We have no idea what’s coming through areas that we do not have a way currently to properly and adequately surveil,” said Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen, during a recent tour of the San Luis, Arizona border wall and port of entry.

“To me,” she said, “that is the definition of a crisis.”

Secretary Nielsen has cited a roughly 200 percent increase in the total number of apprehensions along the Southwest border in March 2018, as compared to March 2017.

But a year-to-year comparison could tell another story. The total number of arrests in 2017 dropped to a 46-year low, and President Donald Trump took credit for it, while calling it “still unacceptable” on Twitter.

More agents ‘on the front lines’

While the president requested up to 4,000 National Guard troops, the governors of the country’s four border states — California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas — have to date supplied only about a quarter of that number.

“It’s never enough,” said Vinny Duleksy, Special Operations Supervisor for U.S. Border Patrol, Yuma Sector.

Based in Arizona, Dulesky told VOA the region has seen an uptick in “OTMs” — short for “other than Mexicans” — who are turning themselves in between ports of entry.

The National Guardsmen, he says, are not actually apprehending border crossers. But that doesn’t mean they’ll benefit border agents any less.

“[The National Guard] is going to free up those support elements that are usually filled by agents, to get more of our line agents on the front lines,” he said.

In practical terms for the deployed troops, that means “maintenance, clearing roads, [and] helping administratively and logistically,” according to Captain Macario Mora, Public Affairs Officer for Operation Guardian Support, which oversees the National Guard’s coordinated effort with Border Patrol agents.

Among the troops are border-area residents who work full-time in other jobs, including police officers, welders, teachers — an array of civilian sector jobs that Mora says make them a versatile force.

“We’ve been deployed throughout the world and supportive of our nation’s defense, so the folks here in this state are more than capable,” Mora said.

Additional lives lost

The National Guard may be armed only in limited circumstances for self-defense, according to U.S. Border Patrol Chief Ronald Vitiello. But guns or not, their presence does not sit well across the border.

“We’re not at war,” remarked Oropeza Rodríguez. “We’re supposedly ‘partner countries,’ right?”

Oropeza Rodríguez says past deployments have had adverse consequences, and she doesn’t believe this time will be any different.

“If anything, it’s more expensive in human lives lost,” she claimed. Previous call-ups “brought more migrant deaths, and why? Because they are forced to cross through more difficult and risky routes, but it doesn’t stop their migration.”

Yet some migrants admit the U.S.’ layered approach to security, including the National Guard deployment and use of surveillance technology, is a clear deterrent.

“The border is tightly guarded. There are no more possibilities,” said 17-year-old César Fernández Morales, a Zacatecas, Mexico-native who sought better economic opportunities for his family, before he was apprehended by U.S. Border Patrol.

The dangers Morales faced in his first attempt, he added, were enough to convince him to avoid returning.

‘Frijolitos, pero todos juntos’

Laura Elena Jiménez, a coordinator at Mexicali’s Mana Pastoral Center, a shelter for adult men, says she frequently asks would-be crossers the same question:

“Why don’t you stay in your country, with your family — frijolitos pero todos juntos?,” which translates roughly to “only beans, but at least you’re together.”

Often escaping from violence in Central America, they respond to her the same way: “You don’t understand.”

Still, Jiménez entreats migrants to think twice before attempting the dangerous journey by foot. Later, when some of them return, claiming “defeat,” she weighs in again.

“I tell them, ‘No, you’re not returning defeated. You’re returning alive,’” Jiménez said.

“Many have stayed on the path and wanted to return but couldn’t. ‘Hold on to that,’ I tell them.”