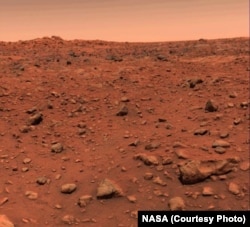

Forty years ago, NASA landed a spacecraft on the surface of Mars, giving us our first close-up view of the so-called Red Planet. And, in what seems to be standard protocol for NASA missions, the 90-day operation stretched into a six-year mission, paving the way for later Mars rovers like Opportunity and Curiosity.

The Viking 1 spacecraft touched down on the Martian surface on July 20, 1976, seven years after Apollo 11 astronauts stepped out onto the moon. The landing was originally scheduled for America’s Independence Day, July 4. But once in orbit around Mars, the satellite carrying Viking revealed that the landing site was incredibly rocky, notes Bill Barry, NASA’s chief historian. So mission controllers adjusted the date so the spacecraft could find a smoother place to land.

The Viking mission was a huge success from an engineering perspective, an 11-month journey through space to a perfect landing on another planet. The heat shield and parachute design were updated and used in subsequent missions to Mars. And Viking’s measurements of the Martian atmosphere and surface are being used and analyzed to this day.

But scientists were really anticipating the results from the life sciences payload carried by the lander. This apparatus housed four different tests in a space the size of a soccer ball, according to Glenn Bugos, historian for the NASA Ames Research Center.

A week after landing, soil samples were put through this barrage of tests to look for evidence of life: mainly carbon molecules and gases released by organisms metabolizing a variety of nutrients that had been added to the soil. Three tests came up negative.

But the fourth one had a promising result… at least initially. In this test, water, nutrients and a radioactive form of carbon were added to the Martian soil. If any organisms ate the radioactive nutrients, they would emit a specific gas. The lander detected this gas spewing out of the soil during the first time it ran the test. But during the next two trials, there was nothing.

This has puzzled scientists for decades. Some researchers have tried to recreate the tests here on Earth and their results have led some scientists to say the tests were “inconclusive” instead of “negative.”

At a panel discussion on the history of the Viking 1 mission, Bugos said that the lack of definitive results killed the desire to search for life on Mars.

Erik Conway, a historian for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, added that a change in political focus towards NASA’s shuttle program and the failed 1984 Mars Observer mission also contributed to the 17-year gap before another lander was sent to Mars.

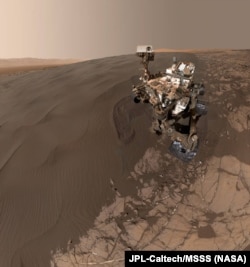

Opportunity and Curiosity, two of the new rovers, focused more on studying the ancient conditions of Mars to see if it was once suitable for life. They each found evidence of water on Mars in the past. Curiosity also noticed that methane periodically increases, which is most likely because of chemical reactions between the Martian rocks and water. But there is a small chance it could be released by living organisms.

So, 40 years after we reached it, humanity is still holding onto hope that life exists - or once existed - on the Red Planet.