The U.S. space agency, NASA, has mapped the massive plume of dust and debris created by the Chelyabinsk meteor that exploded over Russia last February with the force of 30 Hiroshima atom bombs.

Measuring 18 meters across and weighing 11,000 metric tons, the meteor screamed into Earth's atmosphere on February 15 at 18.6 kilometers per second. Burning from the friction with Earth's thin air, the space rock exploded 23.3 kilometers above Chelyabinsk causing extensive damage in the region.

The explosion also deposited hundreds of tons of dust in the stratosphere, allowing a NASA satellite to make unprecedented measurements of how the material formed a thin but cohesive and persistent stratospheric dust belt.

"We wanted to know if our satellite could detect the meteor dust," said atmospheric physicist Nick Gorkavyi of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who led the meteor study. "Indeed, we saw the formation of a new dust belt in Earth's stratosphere, and achieved the first space-based observation of the long-term evolution of a bolide [meteor] plume."

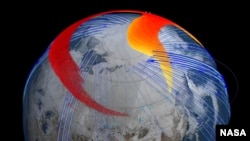

Combining satellite observations with atmospheric models, Gorkavyi and his colleagues created a model of how the plume from the explosion moved around the Northern Hemisphere.

According to NASA, within hours of the impact, an ozone mapping instrument on the NASA-NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite detected the plume high in the atmosphere at an altitude of about 40 kilometers, quickly moving east at more than 300 kilometers per hour.

Within a day the plume continued to flow east and had reached the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. As the plume moved, larger particles began to fall out of it, but smaller particles stayed airborne.

By February 19, the faster, higher portion of the plume had snaked its way entirely around the Northern Hemisphere and back to Chelyabinsk. But the plume’s evolution continued. At least three months later, a detectable belt of dust persisted and could be seen around the planet.

"With all of this technology, we can achieve a very different level of understanding of injection and evolution of meteor dust in atmosphere," Gorkavyi said. "Of course, the Chelyabinsk [meteor] is much smaller than the 'dinosaurs killer,' and this is good. We have the unique opportunity to safely study a potentially very dangerous type of event."

The “dinosaurs killer” is scientific shorthand for the giant meteor or asteroid that hit the Earth about 65 million years ago, creating a dust cloud that many researchers say was responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs and many other species.

NASA says that every day, about 30 metric tons of small material from space encounters Earth and is suspended high in the atmosphere.

NASA’s Chelyabinsk meteor study is to be published in the journal, Geophysical Research Letters.

Here's a short video on the spread of the plume:

Measuring 18 meters across and weighing 11,000 metric tons, the meteor screamed into Earth's atmosphere on February 15 at 18.6 kilometers per second. Burning from the friction with Earth's thin air, the space rock exploded 23.3 kilometers above Chelyabinsk causing extensive damage in the region.

The explosion also deposited hundreds of tons of dust in the stratosphere, allowing a NASA satellite to make unprecedented measurements of how the material formed a thin but cohesive and persistent stratospheric dust belt.

"We wanted to know if our satellite could detect the meteor dust," said atmospheric physicist Nick Gorkavyi of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who led the meteor study. "Indeed, we saw the formation of a new dust belt in Earth's stratosphere, and achieved the first space-based observation of the long-term evolution of a bolide [meteor] plume."

Combining satellite observations with atmospheric models, Gorkavyi and his colleagues created a model of how the plume from the explosion moved around the Northern Hemisphere.

According to NASA, within hours of the impact, an ozone mapping instrument on the NASA-NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite detected the plume high in the atmosphere at an altitude of about 40 kilometers, quickly moving east at more than 300 kilometers per hour.

Within a day the plume continued to flow east and had reached the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. As the plume moved, larger particles began to fall out of it, but smaller particles stayed airborne.

By February 19, the faster, higher portion of the plume had snaked its way entirely around the Northern Hemisphere and back to Chelyabinsk. But the plume’s evolution continued. At least three months later, a detectable belt of dust persisted and could be seen around the planet.

"With all of this technology, we can achieve a very different level of understanding of injection and evolution of meteor dust in atmosphere," Gorkavyi said. "Of course, the Chelyabinsk [meteor] is much smaller than the 'dinosaurs killer,' and this is good. We have the unique opportunity to safely study a potentially very dangerous type of event."

The “dinosaurs killer” is scientific shorthand for the giant meteor or asteroid that hit the Earth about 65 million years ago, creating a dust cloud that many researchers say was responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs and many other species.

NASA says that every day, about 30 metric tons of small material from space encounters Earth and is suspended high in the atmosphere.

NASA’s Chelyabinsk meteor study is to be published in the journal, Geophysical Research Letters.

Here's a short video on the spread of the plume: