WASHINGTON —

The U.S. space agency is adapting tools it has used to learn about water on the moon, minerals on Mars and the composition of exoplanets to analyze ecosystems on planet Earth. NASA this week finished a month of preliminary high-altitude tests of a new Earth-imaging instrument package, which the agency plans to launch into orbit.

The instruments have been flying on NASA’s ER-2, an aircraft that skirts the edge of space at an altitude of 20,000 meters, nearly two times the cruising altitude of commercial jetliners.

The imaging tools gather data about how different wavelengths of light interact with landscape molecules and particles to produce a spectral fingerprint. According to Robert Green, a scientist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and principal investigator on the Hyperspectral Infrared Imager or airborne campaign (HyspIRI), sensors for an instrument called the Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer precisely measure the light and temperature characteristics of each ecosystem the plane overflies.

“We can see the interaction of the molecules that are present in the earth’s atmosphere, such as water vapor and carbon dioxide, and on the earth’s surface in plants such as cellulous and leaf water and the other constituents of plants," he said.

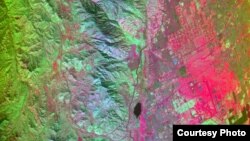

The tool, whose imaging spectroscopy technology was tested over California’s varied landscape, can also measure the impact of surface events such as volcanic eruptions, wildfires and droughts.

“We have snow-covered mountains, we have coasts, we have agriculture, we have deserts, we have forested areas," Green said of the testing region along the nation's western edge. "So in one fairly small region of the country, we can capture a tremendous diversity of ecosystems and environments found on the surface of the Earth.”

Green says each pixel captured by the imager holds a wealth of information invisible to the human eye. “We can map the species type. We can look at the bio-geochemistry of the plants, [and determine] the state of the chemicals in the leaves of the plant to tell us about their health and productivity," he said. "In the geology area, we can look at the different mineral signatures, which tell us the molecules in the rocks to know exactly what those minerals are.”

The test flights, he adds, are part of preparations for an eventual satellite mission that will provide global coverage from low-Earth orbit, about 700 kilometers above the planet.

“This would give us global direct measurements of molecules and temperatures of the Earth’s surface, repeated each year, so we could see seasonal and temporal variations," he said.

The HyspIRI satellite mission is still in the study phase, with ER-2 test-flights continuing through 2014.

Green says the new images of the planet could help scientists better assess how Earth is changing and possibly help policymakers and the public make better-informed decisions about how humans can adapt to the changes.

The instruments have been flying on NASA’s ER-2, an aircraft that skirts the edge of space at an altitude of 20,000 meters, nearly two times the cruising altitude of commercial jetliners.

The imaging tools gather data about how different wavelengths of light interact with landscape molecules and particles to produce a spectral fingerprint. According to Robert Green, a scientist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and principal investigator on the Hyperspectral Infrared Imager or airborne campaign (HyspIRI), sensors for an instrument called the Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer precisely measure the light and temperature characteristics of each ecosystem the plane overflies.

“We can see the interaction of the molecules that are present in the earth’s atmosphere, such as water vapor and carbon dioxide, and on the earth’s surface in plants such as cellulous and leaf water and the other constituents of plants," he said.

The tool, whose imaging spectroscopy technology was tested over California’s varied landscape, can also measure the impact of surface events such as volcanic eruptions, wildfires and droughts.

“We have snow-covered mountains, we have coasts, we have agriculture, we have deserts, we have forested areas," Green said of the testing region along the nation's western edge. "So in one fairly small region of the country, we can capture a tremendous diversity of ecosystems and environments found on the surface of the Earth.”

Green says each pixel captured by the imager holds a wealth of information invisible to the human eye. “We can map the species type. We can look at the bio-geochemistry of the plants, [and determine] the state of the chemicals in the leaves of the plant to tell us about their health and productivity," he said. "In the geology area, we can look at the different mineral signatures, which tell us the molecules in the rocks to know exactly what those minerals are.”

The test flights, he adds, are part of preparations for an eventual satellite mission that will provide global coverage from low-Earth orbit, about 700 kilometers above the planet.

“This would give us global direct measurements of molecules and temperatures of the Earth’s surface, repeated each year, so we could see seasonal and temporal variations," he said.

The HyspIRI satellite mission is still in the study phase, with ER-2 test-flights continuing through 2014.

Green says the new images of the planet could help scientists better assess how Earth is changing and possibly help policymakers and the public make better-informed decisions about how humans can adapt to the changes.