Myanmar’s youth leaders are determined to avoid the military’s conscription law that could see them fight against the very resistance they are part of.

The Myanmar’s People Military Service Law, which was enacted in 2010 but activated in February, means men ages 18 to 45 and women ages 18 to 35 can be drafted into the armed forces for two years. People in certain professions, such as doctors, must serve for three years. In the case of a national emergency, the military service could be extended to a total of five years.

The country’s ruling junta is aiming to draft 60,000 new recruits a year, with 5,000 by the end of April, according to Zaw Min Tun, the spokesperson for Myanmar’s military government.

Robert Minn, 25, is a youth activist for Milk Tea Alliance-Friends of Myanmar, an advocacy group that spans several East Asia nations. He told VOA he was recently stopped at a checkpoint in Yangon and asked to join the army.

“Last week I went downtown, and they checked my phone,” he said. “I have nothing on that phone, no political stuff. But they asked, ‘Are you willing to serve in the military? Are you willing to join this conscription?’”

Faced with intimidation, Minn said he was determined to get away.

“I said no, but there was a lot of soldiers, so I said if you officially call me with a letter, I might join,” he said.

Minn said he paid the soldiers 50,000 MMK (Burmese Kyat), which is $23.80, just to leave the checkpoint.

“It didn’t mean [that I wanted] to join them,” he said. “I just had to pay money to escape. If I said yes, they might have recruited me at that place. The previous times [the military] were just checking identification cards and I can easily pass, but this time was tricky.”

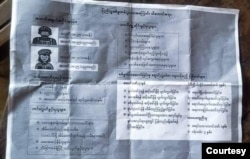

Government leaflets encouraging young people to sign up have been distributed throughout Myanmar since the conscription law came into effect on February 10.

But Aung Sett, an activist with the All Burma Federation of Student Unions, said the conscription law threatens to force individuals to sign up “against their will.”

“They are forcing youths and young students to leave the country or take up arms to join the fight, leaving no choice,” he told VOA. "It does have some threats to our group, especially for those living in urban areas. I’m really worried about the young people, that they might be recruited against their will.”

Myanmar has been in chaos since military leader General Min Aung Hlaing and his forces overthrew the democratically elected government in February 2021. The coup sparked an armed revolution that has persisted for three years.

The Myanmar resistance includes the civilian-led National Unity Government; its armed wing, the People’s Defense Force; and ethnic armed groups.

An offensive by resistance forces that began in October in Myanmar’s Shan State saw dozens of military-held townships and posts captured. Despite a cease-fire, conflict continues to rage in other parts of Myanmar, with the junta struggling to take back control.

With Myanmar’s army now seeking more recruits, millions are eligible. Out of a population of 56 million, 14 million — 6.3 million men and 7.7 million women — qualify for military service, according to the junta.

Jewel, who asked that her real name not be used for security reasons, is part of the Pazundaung Youth Strike Committee, an anti-junta group in Yangon. She said the new conscription law could put women in danger.

“The military service law for women is very worrying during the coup regime because the army rapes women. If not, it will be as a human shield, to carry military equipment or find a [land] mine," she said from Myanmar by phone.

Reports of rape have been frequent during the military’s violent crackdowns on resistance forces in recent years. The junta has previously declined to comment when contacted by VOA.

Jewel said that the conscription law has forced her members to seek protection under pro-democracy opposition forces.

“Members of my group are both male and female. Because of the inclusion of girls, every member of the age set by the conscription law fled to the People’s Revolutionary Army because they did not want to serve in the military,” she said.

Zarni Soe, a Rohingya youth and human rights activist and founder of the Arakan Youth Peace Network, says his group has also faced significant challenges in recent weeks. Reports say hundreds of Rohingya youths have been detained by junta forces in the state, raising concerns over whether the military will conscript them.

“As a result, I have had to halt practical activities in the region since then. To safeguard my efforts, I prioritize discretion, utilizing secure communication channels, adopting movement carefully and building a robust network from several areas,” he told VOA.

The possibility of military service has seen thousands of Myanmar nationals try to leave the country. There have been long visa queues at the Thai Embassy in Yangon, while dozens of Myanmar nationals have been arrested by Thai authorities after illegally entering Thailand.

Ye Myo Hein, global fellow at the Wilson Center and visiting fellow at the United States Institute of Peace, said the military activated the conscription law because of the lack of interest in the population for joining the army.

“With increasing public animosity towards the military following the coup, voluntary enlistment has become virtually impossible,” he said in February.

"If the junta continues with forced and coercive methods, the public will have a few options, including to flee the country, to increase tangible support to the resistance movement to fight against the junta, and to join the resistance themselves,” he said.