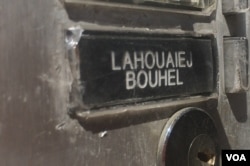

"The president and the media blamed Islamic State militants immediately after the attack," says Wissam, waving his arms for emphasis a few blocks from the former home of Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, the trucker who killed 84 people last week in Nice, France.

"When I saw the picture of him, I was surprised," he continues. "I knew him. He drinks. He smokes hash. He's not with Islamic State."

In recent days, details have emerged that indicate Bouhlel was interested in Islamist extremism, but nothing has pointed to his membership in an extremist group. However, locals say his assumed affiliation with Islamic State is further ostracizing the Arab community in Nice.

In the quiet neighborhood where Bouhlel lived, a few neighbors are quick to denounce the man, reportedly also a brawler, a playboy, a pork eater and a wife beater. Wissam, who is originally Tunisian but has lived in France for 20 years, rails against the killer, and against how authorities and the media have reacted to the tragedy.

The Arab community in Nice has long felt like the "other," Wissam says. But after the attack, he adds, racism against Muslims is reaching a boiling point, and officials are using fear of IS as a rallying cry for political ends. As a result, Wissam is afraid to go outside his neighborhood at night for fear of harassment.

VOA visited police to ask if authorities were concerned with growing tensions, but received no response.

"Politicians can be serpents," Wissam says. "After they speak, people are terrified."

Beyond increased Islamophobia, says Tahar Mejri, 38, who lost his four-year-old son, Kylan, and his ex-wife Olfa in the attack, many Muslims were among the victims as the truck plowed through crowds watching the fireworks.

"No one with a heart or feelings could kill people like this," says Mejri, before departing for Tunisia to bury his dead. "My son was my whole life."

Extremists in Nice

At a café on the other side of town, only a few meters from the promenade where the gruesome rampage took place, Sheikh Otman Aissaoui, Nice's top Imam, says only a tiny fraction of Muslim young men in Nice have joined Islamic State militants.

But Bouhlel, he adds, seems less of a committed extremist than a disturbed person searching for meaning.

"Islamic State people can send information to young people from thousands of kilometers away in Syria through the internet," he says. "A person who is weak can be influenced deeply enough to adopt their ideas."

Investigators say Bouhlel's phone revealed he used dating websites and watched beheading videos. Officials say he must have been radicalized extremely quickly, as he was not known to attend mosque services until very recently.

Whether he was convinced by Islamic State propaganda to attack the people of Nice or simply indulged in gore is not clear. The Islamic State has called him a "soldier" heeding their call to battle, but the group has made no claim to have planned and executed the attack.

The murky motives of Bouhlel, who may have been a lone wolf attacker, however, do not mean there are not real extremists in Nice, says Aissaoui.

Religious authorities try to identify young people at risk, but the process of de-radicalization is delicate.

"The first thing I do is listen to the youth who are lost," he explains. "They have just been released from jail, or have family problems. Outsiders prey on the weak, telling them, ‘Come with us. Leave Nice and your problems and come to freedom.'"

Increasing fears

At a TV repair shop near his house, the owner laughs nervously when asked if he thinks Bouhlel was a supporter of Islamic State.

"He wasn't with Islam in any way," he says, stumbling slightly to mime a drunk. "He was always like this."

Like other local Arab people, the shopkeeper is quick to comment on Bouhlel's un-Islamic habits. But he is also quick to end the conversation, and other locals are quick to refuse to join in.

"If people talk to you, the police will come around," he says, ushering us out the door.

Down the road, Wissam's friends ask him to keep quiet and temper his criticism, lest he attract unwanted attention.

"My daughter is French. My wife is French," Wissam replies, near tears. "The Nice authorities are making the people hate Arabs."

WATCH: Tahar Mejri Talks About Losing his Son in the Attack