Americans were forced to wait a bit longer for news about special counsel Robert Mueller's investigation into foreign meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign.

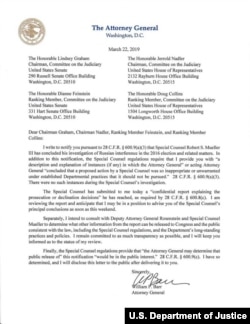

Mueller delivered the confidential report on his probe Friday to Attorney General William Barr, who then told congressional leaders by letter that “I may be in a position to advise you of the special counsel’s principal conclusions as soon as this weekend.”

But Barr spent Saturday reviewing the report, and as of midafternoon, according to a Justice Department spokesman, his summary for Congress was not expected for at least another day.

White House spokesman Hogan Gidley said the White House had not received and had not been briefed on the report. Echoing comments of the night before from White House press secretary Sarah Sanders, he said the next steps in the investigation were up to Barr.

Key questions

The central questions that Mueller, a former FBI director, set out to answer: Did Donald Trump or his aides collude with the Russians to undermine Democrat Hillary Clinton's campaign in 2016 with embarrassing emails stolen from the Democratic National Committee and Clinton's campaign chairman? Or was the president-to-be merely the fortunate beneficiary of Russia's malicious tactics? And did Trump attempt to torpedo the subsequent investigation to protect himself and his political advisers and aides?

The probe has led to the indictments of 37 individuals and entities, mostly Russian operatives who remain at large. Seven people, including five former Trump associates, have pleaded guilty and five have been sentenced to prison.

Among high-profile cases, former national security adviser Michael Flynn pleaded guilty of lying to the FBI about conversations with the Russian ambassador, and Paul Manafort, the president's former campaign chairman, was recently sentenced for a host of crimes.

Ahead of the report's delivery, speculation was rife that the special counsel would bring additional indictments, but there was no additional legal action before the report was released to the Justice Department.

With the report's delivery, the Mueller investigation is effectively over, but not the president's legal troubles. In recent months, Mueller has farmed out parts of his investigation to U.S. attorney's offices, including the Southern District of New York, where prosecutors have opened separate investigations into the Trump Organization and other Trump entities.

WATCH: After Months of Anticipation, Mueller Probe Concludes

Where the case stands

Whether Mueller's report will lead to vindication for the president, his impeachment, or some sort of messy, in-between alternative is unknowable for now.

By law, Barr decides what parts — if any — of the document to disclose to Congress and the public.

Trump has repeatedly called the special counsel investigation a "witch hunt" and insists there is no evidence of his collusion with the Russians. While the president has said "I don't mind" if the report is made public, there is likely to be considerable legal wrangling between the White House, the Justice Department, Trump's personal lawyer and Congress before portions or all of the report are released.

Justice Department regulations require Mueller to submit a "confidential report" of his findings to the attorney general, and the attorney general to "notify" Congress about it. There are no requirements for Mueller to make his findings public.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, however, told House Democrats that the full report must be released to Congress.

The California Democrat sent a letter to colleagues ahead of an ``emergency'' call with all rank-and-file lawmakers Saturday to discuss where Democrats ``go from here'' in their oversight of the White House.

She further said she would reject a classified briefing because members of Congress must be allowed to discuss it publicly. The bottom line, she said on the call is that the American people "deserve the truth"

Wherever the report takes the United States as a country, understanding where it began and the route it followed will be every bit as important as recognizing the final destination.

The beginning

The special counsel investigation began on May 17, 2017, with Deputy Attorney General Rod J. Rosenstein's announcement that he had appointed Mueller to take over an ongoing FBI investigation into connections between the Trump campaign and Russian election interference.

At the time, Rosenstein stressed that the appointment should not be seen as confirmation that there had actually been any illegal coordination between the Trump campaign and Russian officials, and said that transferring day-to-day control of the investigation to Mueller was meant to assure the public that the inquiry was free of political bias.

Mueller was not starting from scratch. The investigation he inherited had begun nearly a year before, on July 31, 2016, after the FBI learned of possible collusion between a Trump campaign adviser and Russia.

'Dirt' on Clinton

The tip that initially led investigators to open the case came from Australia's top diplomat in the United Kingdom, who had encountered Trump foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos at a bar in London months earlier.

The diplomat revealed Papadopoulos, while drinking, said he had reason to believe Russian officials were in possession of "dirt" that could damage the candidacy of Clinton, the former secretary of state and front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination.

On July 22, 2016, when the anti-secrecy website WikiLeaks published about 20,000 emails stolen from the Democratic National Committee, the Australian government reached out to the FBI and took the highly unusual step of allowing the official who encountered Papadopoulos — High Commissioner to the United Kingdom Alexander Downer — to be interviewed by investigators.

U.S. intelligence officials were already convinced that Russia was behind the DNC hacking and other efforts to influence the presidential election. But the Downer interview added a new and possibly explosive angle.

The diplomat presented the FBI with credible evidence that a Trump campaign official had specific information about Russian interference in the U.S. elections months before that interference was made public. That forced the agency to open an urgent counterintelligence investigation examining whether the Trump campaign was colluding with Russia.

An investigation in the public eye

By September 2016, intelligence officials had briefed members of Congress on Russian election interference, but it wasn't until after Nov. 8, when Trump unexpectedly captured the Oval Office, that some of the most important details about Russian intentions became public.

By that time, further leaks of emails stolen from the account of Clinton campaign manager John Podesta and posted online by WikiLeaks reinforced suspicions that the hacking efforts weren't just meant to sow chaos by Russian President Vladimir Putin's government but were aimed at aiding the Trump campaign. The intelligence community confirmed as much in a closed-door meeting with select lawmakers in November, and would make that conclusion public in early January 2017.

Meanwhile, FBI investigators working on the probe were monitoring a large number of interactions between members of the Trump transition team and Russian officials.

Within a few weeks of Trump's inauguration, those interactions would cost a prominent member of the Trump administration his job. National security adviser Flynn, a retired three-star Army general, was forced to resign after it was revealed he had lied to the FBI about his communications with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak.

Flynn's fate led, albeit indirectly, to the Russia investigation being handed over to Mueller in spring 2017.

Trump's choice for attorney general, former Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama, recused himself from supervising the Russian investigation because he had served as a senior adviser to the Trump campaign, which posed a conflict of interest. That decision angered Trump, and left the Justice Department's second-in-command, Rosenstein, in charge of the investigation. FBI Director James Comey disclosed the existence of the investigation during a testimony before Congress in March.

In private meetings with Comey, Trump demanded "loyalty" from the career law enforcement officer, and pressed him to drop the investigation into Flynn, Comey later testified. Comey refused the president's request.

By May, Trump fired Comey, saying later in a TV interview that he did so largely because of the Russia investigation, to which he strongly objected.

To insulate the investigation from political interference, Rosenstein on May 17 appointed Mueller as special counsel for the Russia investigation.

In his letter appointing Mueller, Rosenstein authorized the special counsel to investigate "any links and/or coordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump; and any matters that arose or may arise directly from the investigation."

Mueller's mandate was later expanded to include whether Trump had obstructed justice.

Following Comey's firing, Andrew McCabe, then the bureau's acting director, quietly ordered two separate investigations to examine whether Trump had obstructed justice and whether he was acting as an agent of Russia.

Stream of indictments, guilty pleas

In the months after Mueller took over, the public began to see the fruits of an investigation that had, at that point, been ongoing for nearly a year.

In July, Papadopoulos was arrested and charged with lying to the FBI. He later pleaded guilty and received a two-week prison sentence.

In October, former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort and his deputy, Rick Gates, were both indicted on conspiracy and money laundering charges dating back to work they had done for Russian-supported politicians in Ukraine years earlier.

The indictments had nothing to do with the Trump campaign specifically, but were widely seen as providing prosecutors with leverage over Manafort and Gates, who would likely have been privy to any collusion that might have occurred during the election.

The next month, Flynn entered a guilty plea to a charge of lying to the FBI, and agreed to cooperate with prosecutors in multiple investigations.

In February 2018, Mueller's office unsealed an indictment of 13 Russian nationals and three Russian companies, charging them with conspiracy to interfere with U.S. elections. Months later, 12 other Russians were indicted and charged with hacking the email system of the Democratic National Committee and others.

The following months marked a series of major events in the investigation.

In late February, Gates pleaded guilty and promised to assist in further investigations. In April, FBI agents raided the home and office of Trump's personal attorney, Michael Cohen.

In June, Mueller expanded the charges against Manafort to include witness tampering and obstruction of justice, and also named suspected Russian intelligence officer and Manafort business partner Konstantin Kilimnik in an indictment.

By August, Manafort was convicted in the first of two trials for his illicit business practices, and Cohen pleaded guilty of campaign finance violations — implicating Trump in at least one crime — in a case handed off by Mueller to the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York. Notably, though, neither of the convictions touched on Russian election interference.

Manafort later pleaded guilty of additional crimes and agreed to cooperate with prosecutors in exchange for leniency. He would lose that consideration after Mueller and a federal judge determined that he had continued lying to investigators after striking his plea deal.

Cohen pleaded guilty to a further charge of lying to Congress and was sentenced to three years in prison.

An agreement and another arrest

After more than a year of sparring over whether Trump would consent to be interviewed by the special counsel's office, an agreement was reached in late November 2018 in which the president instead submitted written answers to a series of questions from investigators.

In January 2019, Trump associate Roger Stone was arrested and charged with obstruction of justice, five counts of making false statements to Congress, and one count of witness tampering. Investigators had been interested in his potential communication with Russian hackers and their associates during the 2016 election.

'Racist, cheat, con man'

During three days of testimony on Capitol Hill in late February, Cohen lashed out at Trump, his former boss.

During his opening statement to lawmakers, Cohen called Trump, among other things, a "racist," "cheat" and "con man." He also produced documentary evidence that allegedly proved the president's participation in a criminal conspiracy to conceal illicit campaign contributions in the form of payment of hush money to prevent adult-film star Stormy Daniels from going public with her allegation that she and Trump had a sexual liaison years earlier.

Cohen also said, "Questions have been raised about whether I know of direct evidence that Mr. Trump or his campaign colluded with Russia. I do not. I want to be clear."

He did say, though, that he had "suspicions" about connections between the Trump family and Russians who worked to influence the election.

Changing cast members

Today, as the investigation concludes, it is operating under the direction of a different set of presidential appointees.

Trump's frustration with Sessions finally boiled over in late 2018, resulting in Sessions' forced resignation. He was replaced on a temporary basis by his chief of staff, Matthew Whitaker. After a delay, Trump appointed William Barr to fill the role.

Barr, in his confirmation hearing, told senators he would commit to allowing the Mueller probe to run its course. He was less forthcoming when asked to guarantee that the results would be made public.

"My goal will be to provide as much transparency as I can consistent with the law," he said.

Masood Farivar contributed to this report. Some information for this report came from Associated Press.