Long before there was an Islamic State, Muslim jihadists grappled with a nagging conundrum: how to build authentically Islamic states.

While some advocated toppling the near enemy – the so-called atheist regimes and their collaborators — others pushed for striking the far enemy — Western enablers, the United States in particular.

In the 1990s, al-Qaida put the debate to rest by taking the fight to the far enemy, a strategy that culminated in the attacks of September 11, 2001.

As al-Qaida has diminished in power in recent years, though, and given birth to myriad offspring and permutations with often local agendas, including the so-called Islamic State, the near enemy has borne the brunt of terrorist violence.

By far the vast majority of victims of terrorist attacks over the past 15 years has been Muslims killed by Muslims. In the latest instance, an Islamic State suicide bomber struck a Kurdish wedding in southeastern Turkey on Saturday, killing more than 50 people.

“I understand why the media cover terrorism in the West so closely, and I understand why people who follow these events become so frightened, but objectively speaking the threat of terrorism is not very great,” said Richard Bulliet, a professor emeritus of history at Columbia University.

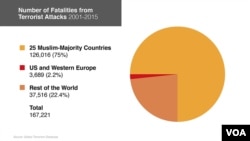

Of 167,221 terrorism-related fatalities reported from 2001 to 2015, almost all — 163,532 or 98 percent — occurred outside the United States and Western Europe, according to the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database. The U.S. government-funded GTD is the world’s largest public database on terrorist attacks.

The database does not sort victims by religious affiliation. But GTD data on 25 Muslim-majority countries from Iraq to Malaysia reveal that these countries account for 75 percent of all fatalities from terrorist attacks from that period. The United States and Western Europe, with a combined 3,689 fatalities — including 2,977 from the attacks of September 11, 2001 — account for just 2.2 percent of terrorism-related deaths during the period.

Not all victims of terrorism in Muslim-majority countries are Muslims. In fact, the fatalities have included Christians, Yazidis and other minorities just as there have been many non-Christians among casualties of terrorism in the U.S. and Western Europe. But it is safe to assume that the majority of victims in Muslim countries are Muslims, according to Michael Jensen, GTD data collection manager.

Driven by more than religion

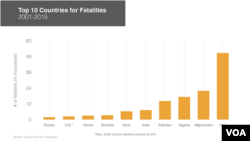

The GTD data vary wildly from country to country. While Iraq accounts for more than 50,000 fatalities, Malaysia shows only six deaths for the past 15 years.

In many cases, the motive never becomes clear but the discrepancy in terrorism related fatalities among Muslim countries suggests that “it’s not just religion driving it,” Jensen said. “It has to be something else.”

Researchers at the Institute for Economics and Peace have combed the GTD data for patterns and identified two features common to countries where terrorism thrives. According to their research, 92 percent of all terrorist attacks in the past 25 years have occurred in countries with widespread state-sponsored political violence, while 88 percent of attacks have occurred in places with violent conflicts.

“The link between these two factors and terrorism is so strong that less than 0.6 per cent of all terrorist attacks have occurred in countries without any ongoing conflict and any form of political terror,” the researchers write in the 2015 Global Terrorism Index Report.

In most Muslim-majority countries with a significant level of terrorist activity, one or both of these features are present. Iraq may be the most extreme example of a country with a long history of state-sponsored violence and conflict over political authority. At the other end of the spectrum is Egypt, where authoritarian regimes have long sanctioned violence against political opponents.

Categories of targets

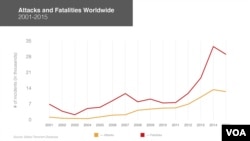

Historically, terrorism travels in waves. In the 1960s and 1970s, with wars raging in Vietnam and Algeria and a conflict in Northern Ireland, the epicenter of terrorism was Western Europe and to a lesser extent, the U.S.

In the 1980s, the focal point shifted to Latin America where insurgencies in Peru, El Salvador and Colombia spawned a wave of terrorism in the region. Since the 1990s, the predominantly Muslim countries of the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa have served as the hotbed of global terrorism, as jihadists, emboldened by the fall of the Soviet Union, have sought to bring down regional governments.

GTD’s Jensen said that in Muslim-majority countries, as in most other countries with a history of terrorism, militants often strike three categories of targets: Private citizens and property represent the largest target of terrorist attacks, followed by security forces, and government and diplomatic officials and institutions.

In Afghanistan, “you have a classic example of a progressive expansion of the categories of targets so that you see not only the Taliban but also other groups ... progressively have begun to target individuals that they feel are associated with government,” said Candace Rondeaux, a senior program officer at the U.S. Institute of Peace in Washington.

The victims include teachers and bus drivers “so it’s become a much more expansive category in a lot of cases and you see that replicated in other parts of South Asia, in parts of North Africa and in the Horn of Africa,” Rondeaux said.

The violence has involved Islamic State militants killing Kurds in Turkey, Sunni suicide bombers targeting Shiite mosques in Pakistan, Shiite extremists assassinating Sunni religious figures, Taliban bombs killing civilians in Afghanistan, Islamic State suicide bombers blow up Shiite shrines and massacring members of the Yazidi minority in Iraq, and Boko Haram militants killing peaceful Muslim worshipers and restaurant guests in Nigeria.

“I think in a majority of cases where Muslims are victims of terrorism, they’re largely targeted not because they’re Muslim but because they’re police officers or soldiers or happen to be in a public place,” said Jensen.

Political motivations

Nevertheless, he said Sunni-Shiite sectarianism “is a big part of it.” Proportionally, Shiites, who make up about 10% of the world’s 1.7 billion Muslims, are killed in increasingly large numbers as Sunni extremists from Iraq to Pakistan target members of a minority sect they view as heretical, according to Bulliet.

While not all Shiite groups have been targeted by Sunni militants, ‘’it is striking how often in Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan, you have terrorist outrages that really focused on Shiites,” Bulliet said.

At its core, the violence is part of a broader struggle over power in predominantly Sunni societies where questions over political and religious authority as well as the relationship between religion and modernity linger unsettled decades after European colonial rule and the fall of the Ottoman Empire. With Sunnism collapsing as a unifying state institution, Islamists have turned to religion to combat authoritarian regimes, Bulliet said.

“Sunni Islam… is falling apart drastically, and I think this is the source of a great deal of the violence,” he said. “Ultimately, that’s the problem: If you have an entrenched state, can you get rid of it without violence? If you don’t believe that’s a possibility, then violence becomes the alternative option.”