Minnesota has had 78 cases of measles so far this year, eight more than in the entire United States in 2016.

There have been no new cases in the state since June 16, but health officials are waiting for two 21-day incubation periods to pass without new infections before they declare the outbreak over.

The virus broke out in the Somali-American community in Minneapolis. No one knows how measles came to Minnesota, since the disease no longer occurs naturally in the U.S.

State health workers identified nearly 9,000 people who were exposed to the measles infection. Those people had to be watched, immunized, if they were not vaccinated, and isolated if they became sick. Most of those who were exposed had already been vaccinated.

"It tells us that the vaccine works really, really well," said Patsy Stinchfield, an infectious disease nurse practitioner who said she worked in "the eye of the storm" at Children's Minnesota hospital.

Previous outbreak

Stinchfield has been involved in vaccine work since a measles outbreak in 1990 claimed the lives of three children, two at Children's Minnesota.

"Measles is such a highly contagious disease; all you have to do is be in the same room with someone who is breathing it," Stinchfield said during an interview with VOA via Skype. Ninety percent of those exposed will go on to develop the disease unless they have been vaccinated or have already suffered the infection.

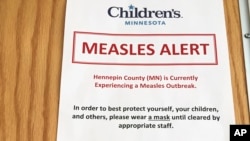

Stinchfield described efforts at Children's Minnesota to contain the infectious disease. She said nurses wearing face masks met people at the doors of the hospital emergency room and at the facility's clinics. They also required the patients to do the same.

All but two of those who contracted measles were children. Twenty-one were hospitalized, mostly for dehydration. There is no treatment for measles, only for its symptoms.

The virus broke out in the mostly Muslim Somali-American community so health workers met with the community's religious leaders, who invited Stinchfield and others to provide information to their followers about the vaccine and measles itself. The imams also encouraged parents to have their children vaccinated.

Stinchfield said Somali-Americans, at one time, had the highest rates of vaccinations against measles in the entire state. Then, she said, the vaccination rate dropped dramatically after anti-vaccination groups told the community that the MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps and rubella, could cause autism.

"I would say almost exclusively the whole responsibility lands on the anti-vaccine movement, and the reason is misinformation and myths spread about a link between MMR and autism, of which there is none, and science has proven that not to be true," Stinchfield said.

In interviews with Somali mothers last month, VOA's Somali Service found that anti-vaccine views in the state are widespread.

Known history with measles

In Somalia, measles is widespread, Stinchfield said, and those in the Somali-American community are familiar with the disease and know that it can kill.

"They did not think that measles would be in the United States, and so the level of fear was greater for autism," Stinchfield said. "This has now shifted, because the level of fear and the level of fear for measles is great because these families know measles. They’ve had loved ones die of measles in Somalia."

Measles can cause a number of medical problems.

"The people who decline vaccines are actually increasing their risk for neurological problems ... encephalitis, brain infections, developmental delay, and it is absolutely taking a risk to do nothing, to decline vaccines," Stinchfield said.

Some researchers, such as Daniel Salmon at the Johns Hopkins University's Institute for Vaccine Safety, maintain that the rubella vaccine can prevent autism. Rubella, which is also prevented by the MMR vaccine, is generally a mild disease, but 90 percent of infants suffer complications, including brain damage, if a pregnant woman contracts it during her first trimester.

Members of anti-vaccine groups, however, say that vaccines expose children to health risks and can cause harm. But, Stinchfield cites the higher health risks of not being vaccinated.

"Anything that can cause neurological impairment should be avoided and so, for example, with measles disease, one in a thousand cases from measles can have encephalitis with permanent brain damage, whereas one in one million doses of measles, mumps, rubella vaccine can have anaphylaxis," a severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction to the vaccine, "and so it really is important to prevent the disease, which is a greater chance of having brain issues."